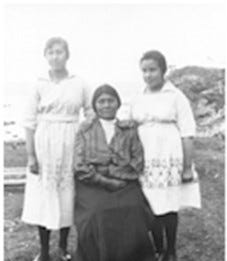

Nelly Calderón Lawrence

A Yahgan woman who paved the way for an Austrian anthropologist to learn about her people

A lot of what the outside world knows about the traditional culture and lifestyle of the Yahgan comes from the British missionary Thomas Bridges, who lived among the Yahgan for 42 years (and whose story is central to my novel). But Thomas Bridges had some important misconceptions and blind spots in his descriptions of his indigenous neighbors—most notably in saying that they had no religious traditions or concepts of the spiritual world.

After Bridges, the other main source of academic information about the Yahgan comes from Austrian anthropologist Martin Gusinde, a Catholic priest trained as an anthropologist who visited Tierra del Fuego four times between 1918 and 1924. He collected Yahgan myths from storytellers and participated in the Yahgan rites of the chiexaus and kina ceremonies. Without him, there might not be any record of those stories or those rites.

And he wouldn’t have had such success in describing Yahgan culture if it weren’t for the bridge-building efforts of a Yahgan woman married to a missionary’s son, the woman known as Nelly Calderón Lawrence.

Nelly was born sometime after 1880. According to anthropologist Anne Chapman, she was named in honor of one of the missionary women, Mrs. Burleigh (who was living at the Falkland Island station at that time, so the girl may have been given the name by other missionaries or by a family member who lived at the Falkland Island station at some point).

Nelly Calderón would have been pretty young when the measles epidemic arrived in 1884. The effects of the disease killed about 60% of her people over the course of two years, which undoubtedly shaped her childhood, as it did the life of everyone who lived through it.

Whether she arrived at the Anglican mission in Ushuaia before or after the epidemic, Nelly grew up there, alongside other “civilized” Yahgan and the missionary families. When she eventually married Fred Lawrence, the second son of long-serving missionary John Lawrence, the family was not very pleased, according to historian Arnoldo Canclini.1

The couple lived at the family’s sheep farm, Estancia Remolino, which was a sort of safe haven and gathering place for many Yahgan families who were threatened by the increasing Argentinian transplants at the government outpost in Ushuaia and the gold miners who had invaded the region.

Cristina Calderón, who became famous as “the last Yahgan,” was Nelly’s niece. She described the memory of Nelly that remained.

She was the lady of the house at Remolino. […] I never met her, but they say she didn’t abandon her Yahgan customs, that she had learned as a child, when she married Frederick Lawrence.

She fed her children what she ate: [local berries] with sea lion grease, cooked sea lion as well. They said my mom would take it to her when she went to Remolino to visit. Nelly would say to her, “Next time you come, bring me sea lion meat so the children and I can have some.”

She would go to the traditional houses, and her husband would get mad. One day he saw that the children’s clothing was stained with sea lion grease, and he scolded his wife, “What did you give these kids?” And she answered, “My food, which you aren’t going to keep me from eating.”

So they said she never left behind her traditional customs.

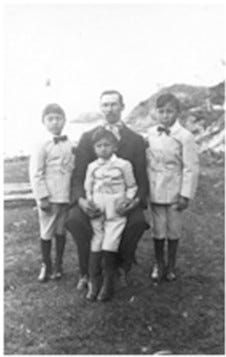

Nelly’s husband, Frederick, was remembered as being very affectionate with his family, but he had a quick temper and could be impetuous, even violent. However, people said the marriage was a happy one, and the couple had six children together (Rosemary, Joyce, Queenie, Federico Falcon, William Martin, and John Edward).

Not much is known about the children, however, beyond the names registered when their grandfather baptized them, because almost all of them died young.2

In his record of the Yahgan, Gusinde wrote about her:

Nelly, a Yahgan woman of the purest blood, in all her ways of being and thinking manifested the characteristics of her people. In her six children the Indian type predominates, but it is more pronounced in the three older girls and less in the three younger boys. From their earliest childhood they spoke Yahgan amongst themselves and with their mother, although they spoke English with their father.3

Anthropologist Anne Chapman says, “Nelly […] did not cling to the old ways. […] Even so she was the anthropologists’ dream come true. She was articulate, trilingual, willing to share her knowledge of her people with outsiders she trusted and to convince others to do likewise, while unforgiving when recalling the horrors that had led to the extinction of her people.”

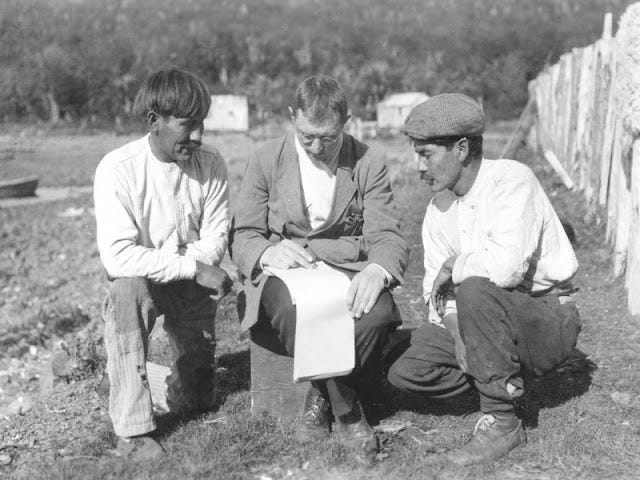

When Nelly met Martin Gusinde, who was in Tierra del Fuego for the purpose of studying its people, she didn’t trust him right away, but it wasn’t long before she decided to help him.

As Gusinde described it, “I myself don’t know how to explain that from the beginning she treated me with such special favor; I had frequently observed that she was timid and shy in front of European guests. But when she saw my sincere desire to respect the authentic cultural heritage of her ancestors, she spared no efforts to make things easier for me and to procure for me anything that would be helpful in my work… Taciturn and impulsive as she was, she actively aided me.”

Nelly became a bridge between Gusinde and her community—such an important one that Gusinde dedicated to her his volume on the Yahgan (who he called “Yamana,” after their word for “people” or “men”). He wrote that his book was “a faithful witness to my sincere gratitude to this simple and noble Fuegian woman of the Archipelago of Cape Horn.”

According to Gusinde, “even the greatest effort on my part would have been unsuccessful in reaching my goal if I hadn’t gotten invaluable help from the good Nelly Lawrence, who smoothed away all difficulties. […] I sincerely thank this energetic and intelligent woman for the unexpectedly beautiful success that I have obtained in the investigation among the Yamana.”

Scholar Johannes Wilbert wrote that “Nelly, once she understood Gusinde’s research goals, took great pride and personal interest in transmitting, for posterity, as much of Yamana culture as stood in her power.”

Gusinde described their process this way: “Nelly went with me to visit the women, seated next to the fire in their huts. They were much more vivacious, or at least more conversational, when she was present. Without me noticing, she made inquiries, along with some of the willing Indian women, about what I had been told and seen.”

In particular, Nelly helped Gusinde understand “the spiritual world of her people,” which “had never before been made accessible to such a degree to any other European.”

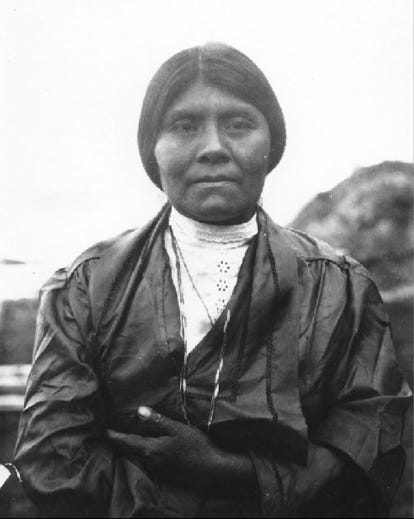

Nelly herself was also candid with Gusinde about her own religious convictions.

As daughter-in-law of the missionary John Lawrence, Nelly lived in the same house and was in daily contact with this profoundly religious man… Convinced in her deepest being, she confessed to me that the traditional faith of Watauinaiwa satisfied her completely and she had no desire for the things John Lawrence told her about frequently when he spoke of his ‘Lord.’ And Nelly Lawrence said, ‘Much more beautiful, incomparable, is everything that the Yamana tell about our Watauinaiwa!’ She communicated this conviction to me many times and with great pride. Her name never appeared in the register of Baptisms, and I never encountered in Nelly Lawrence any sign of Christian faith. She was fine and happy with her faith in Watauinaiwa, Hidabuan (My Father). She was truly a profoundly religious person. She repeatedly explained about the Yamanas: ‘When people die, all union (or relation) ceases between us and that spirit. We don’t know how the spirit enters a child when they begin to live; neither do we known where the spirit goes when a person dies. The spirit goes far away, beyond the seas!

Gusinde wrote: “When we said goodbye for the last time, Nelly assured me that she could now bear the somber destiny of her people more calmly, because she now had the joyful knowledge that all the observations I planned to put in a lengthy book would forever rehabilitate the reputation of her much-maligned countrymen.”

Nelly was in her mid-40s when she succumbed to the flu epidemic that swept through the area in 1924 and killed many of the Yahgan who remembered the old ways.

She was buried in the cemetery at Estancia Remolino—a humble woman whose impact has been felt for generations.

Sources:

Luis Fuentes Ampuero, excerpt from Nelly Calderón Lawrence: La mujer yagán que se casó con el hijo de un misionero inglés (unpublished manuscript), accessed 10 Oct 2024

Arnoldo Canclini, Juan Lawrence: Primer maestro de Tierra del Fuego (Buenos Aires: Marymar, 1983)

Anne Chapman, European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010)

Martin J. Lawrence, “Lawrence” in Ushuaia: 1884-1984, ed. Arnoldo Canclini (Ushuaia: Hanis, 1984)

Víctor Vargas Filgueira, Mi sangre yagán (My Yahgan Blood) (La Plata, Argentina: La Flor Azul, 2021)

Johannes Wilbert (editor), Folk Literature of the Yamana Indians: Martin Gusinde’s Collection of Yamana Narratives, trans. Karin Simoneau (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977)

Cristina Zárraga, Cristina Calderón: Memorias de mi abuela yagán (Memories of My Yahgan Grandmother) (Punta Arenas: Ediciones Pix, 2016)

Canclini doesn’t specify why the family was upset or embarrassed by this marriage. Considering what I know about John Lawrence, I suspect the missionary’s reluctance may have had more to do with the fact that Nelly never embraced Christianity rather than her race, which would have been the principal objection of many British people at the time. Fred Lawrence was known as the troublemaker in his family, and it’s possible he didn’t follow the rules his father would have liked him to respect regarding marriage. In any case, Fred’s younger brother, Albert, also married a Yahgan woman. After Nelly’s death, Fred married twice more, and at least one of those women was Yahgan as well.

Federico Falcón reached adulthood and moved to the Chilean cities of Valparaiso and La Serena, where he died. Her daughter Joyce, the second-born, married a man called Carlos Martínez, who was from Punta Arenas, although she also died without leaving behind any descendants.

Gusinde’s full-length work on the Yahgan/Yamana was published in German, which I don’t read. The quotes from him come from this article about Nelly, whose author presumably translated Gusinde’s words from German into Spanish. The translation from Spanish to English is my own.

I love that she passed the language to her children!

Your note about Bridges’ lack of description of the Yahgan belief system is very interesting! Although he never seems to properly acknowledge it in his ethnographic writings, in his dictionary there are numerous references to spirits, but they are described as characters in “dramas” or “semireligious plays.” Admittedly my knowledge of Yahgan culture is a little more lacking than my research into the language, but I believe a big part of religious ceremonies was men dressing up and acting as spirits in front of women and children. For example, in the final incomplete version of his dictionary, he names Ɛdį́dɑ (= Īdáida, or in the modern orthography Itáita) “A character and scene enacted in the Múrɑnɑ [= Mö́rana or mod. Márana] drama, came in from the woods,” and when describing the čiexaus he has “A term for the rites and ceremonies (being superstitious, lying, obscene dramatic & semireligious plays.” As a missionary it makes sense that he would be dismissive towards Yahgan beliefs, but it’s a little disappointing that he wrote so little on their worldview, since by living among them for decades he surely would’ve had a pretty good understanding of them.