In Praise of an Overlooked Leader

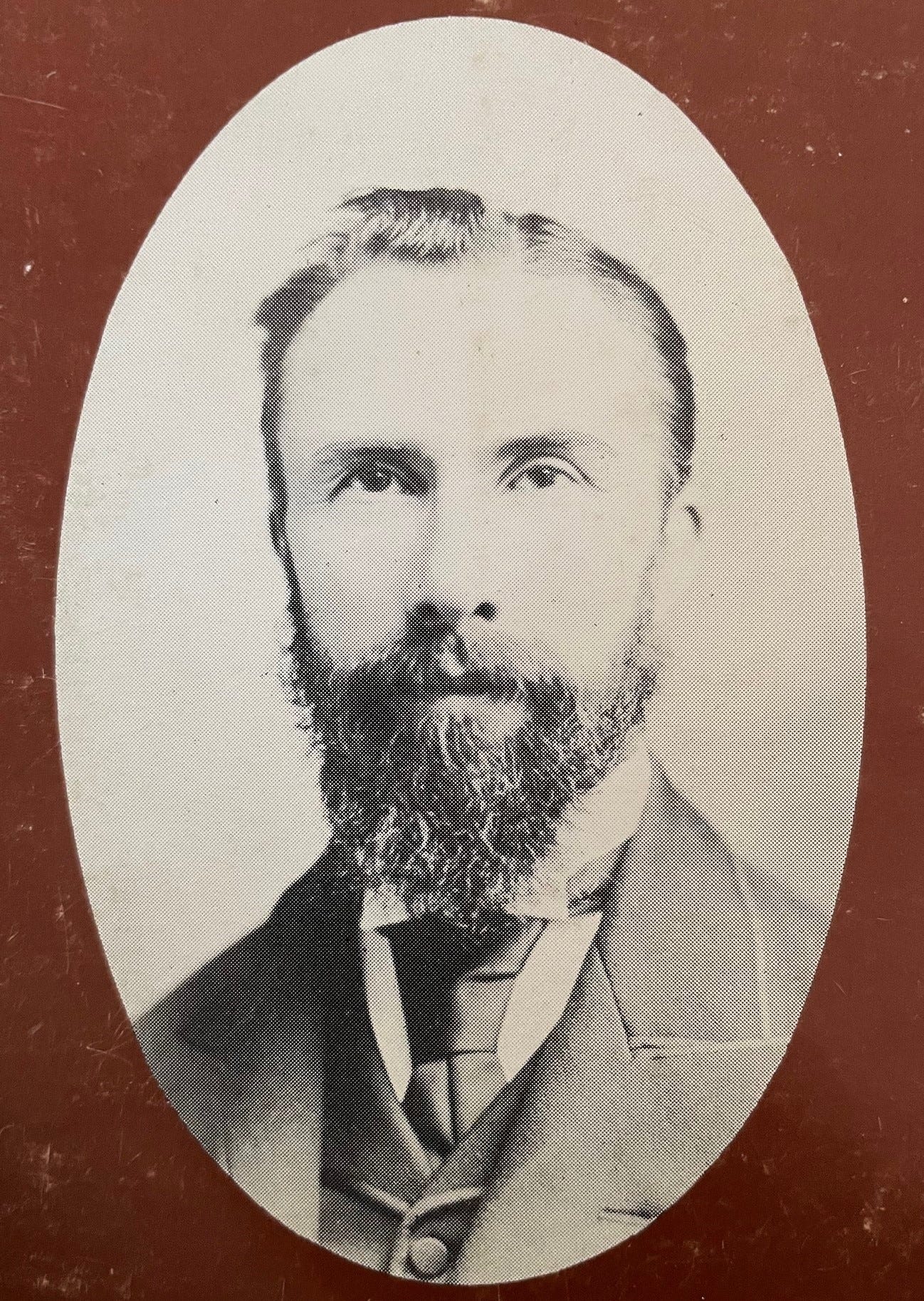

John Lawrence, the first teacher of Tierra del Fuego and second-in-command at the Anglican mission

Leaders with quiet personalities are often overlooked and under praised, particularly when they are second-in-command to someone energetic and dynamic. This was the case for John Lawrence, a British missionary in Tierra del Fuego, the first schoolteacher in Ushuaia, and one of the earliest white settlers in the region.

Though Thomas Bridges was recognized internationally as the leader of the Anglican mission in Ushuaia, even for decades after his death, John Lawrence actually spent more time with the mission: forty years compared to Bridges’ fifteen years. Lawrence was often in charge of the mission when Bridges was traveling, and he stayed in Ushuaia to the mission station’s bitter end.

Even as Tierra del Fuego changed around him, he remained faithful in serving the Yahgan until his death at 89, sixty-four years after joining the mission.

John Lawrence was born in 1844, in Great Malvern, Worcester County, in central England. He grew up in a religious home and attended church regularly, but he had a particular religious experience in his late teens that led him to be more dedicated to his faith. As part of this, he joined a different church and a temperance society.

He was a gardener by trade, though he also taught children. His ambition, however, was to become a missionary. He got in touch with the South American Missionary Society, which hired him to serve in the Yahgan mission as a lay catechist and general assistant.

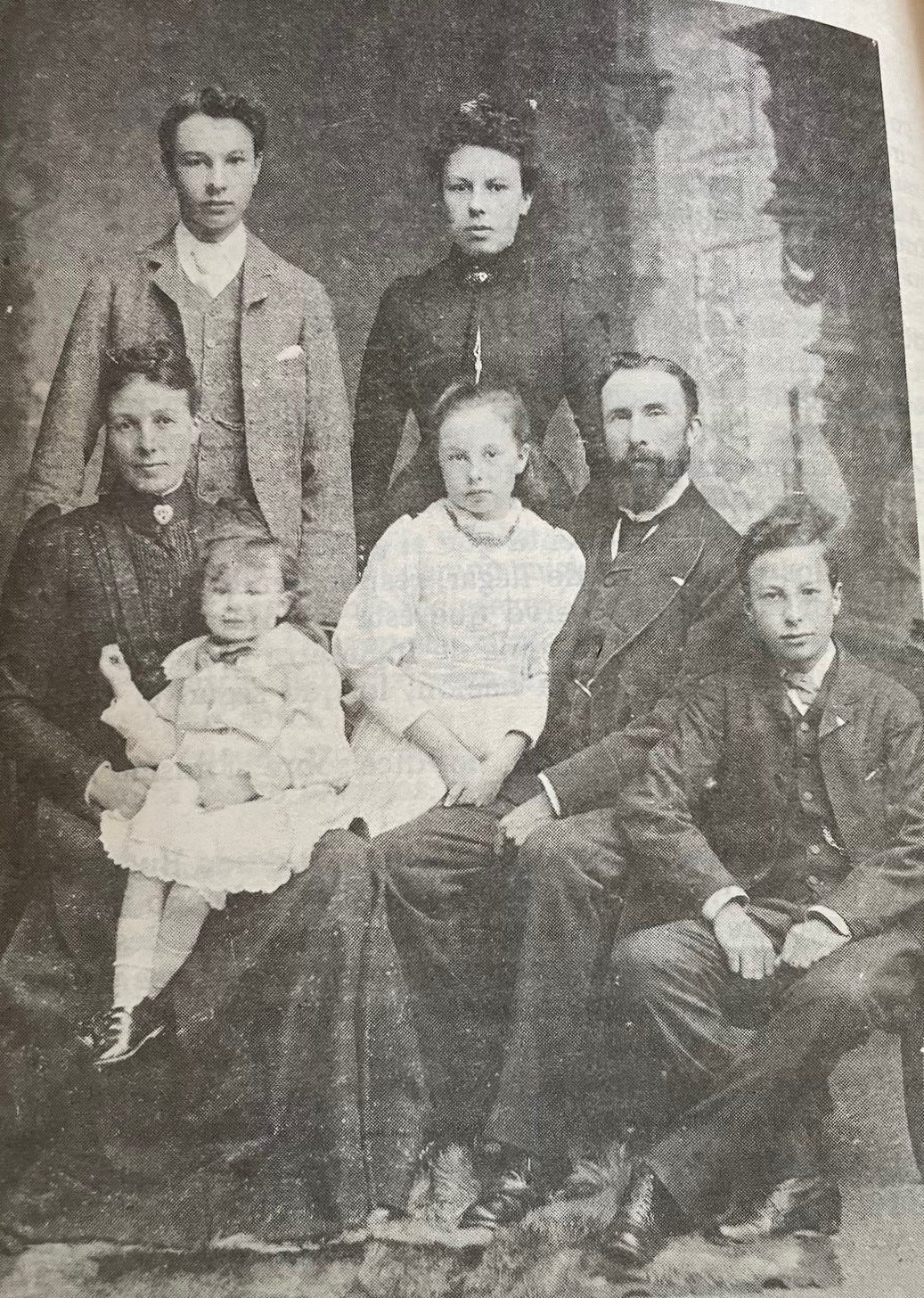

On Aug. 17, 1869, he married Clara Martin, who was a seamstress from his hometown. Forty days later, they were commissioned as missionaries and sent off to South America. He was 25 years old, and she was 20. They embraced their new homeland wholeheartedly and only returned to England once in their long years of service.

Those who knew him described him as quiet, peaceful, and of deep faith. His wife, Clara, was more vivacious and energetic, but also of deep faith. Their marriage, by all accounts, was a happy one, and they had five children together, all born on the mission field.

The first mention of John Lawrence in the South American Missionary Magazine introduces him with the following words: “Mr. Lawrence said he was glad that God, who had long given him a desire to be a missionary, had at length opened the way for him. Now he had been called, all he asked for was the prayers of God’s believing people that he might go forth simply trusting to God to make use of him as long as he was permitted to live.”

Thomas Bridges described Lawrence this way soon after the start of his ministry: “We like Mr. Lawrence well—a truly conscientious, gentle man he is; he and his wife a very pattern of neatness, cleanliness, and order to all.”

According to Argentinian historian Arnoldo Canclini, “One of the glories of John Lawrence was that he endured amidst pain and dedicated his life to a people that was disappearing before his tear-soaked eyes.”

Lawrence’s primary role was to teach children English, singing, reading, and arithmetic. The daily schedule also included recess afterward. His classes combined the children of the Yahgan who lived at the mission with the missionaries’ own children (more numerous as the years went on).

He was fluent enough in Yahgan that he could preach and teach writing in that language, but he never had the ease of languages that Thomas Bridges had. It seems that he never became fully fluent in Spanish, which later on hampered his relationship with Argentinian officials at the government that was eventually created in Ushuaia.

Aside from his daily lessons to the children, Lawrence hosted classes in his home for older students, preached when needed, visited the sick, and kept track of goods in the store room. Later on, he taught a marriage class for engaged couples and founded a temperance group to encourage the Yahgan toward sobriety.

He also assisted in the various tasks of the mission settlement. However, it may be notable that his name isn’t mentioned in helping with construction projects, even when it was all hands on deck to build his family a house. (Historian Arnoldo Canclini surmised John Lawrence may not have been gifted in that area, so that he was more helpful leaving that work to others rather than trying to pitch in.)

In his letters to the mission board, John Lawrence spoke warmly of the Yahgan and praised them regularly (in contrast to the Bridges’ sometimes critical, often patronizing tone toward them). And while Mrs. Bridges declared the Yahgan too dirty to work in her home, the Lawrences hired house help and seemed to form a particularly close relationship with that indigenous family, who became one of the most successful families among the Yahgan connected to the mission.

John Lawrence’s letters also express remarkable humility, such as in this letter, from Dec. 1870.

It is now twelve months since we arrived at Keppel Island. Since that time, we have experienced much of the goodness and mercy of our God. I have been truly happy in the performance of the responsible duties devolving upon me, and my daily prayer is, that God will enable me to be faithful in discharging the same with a single eye to His glory, and the temporal and spiritual welfare of the heathens of Tierra del Fuego.

For the first few years of their mission work, the Lawrences lived at the mission station in the Falkland Islands, but in late 1873, the mission decided that the Lawrences should trade places with another missionary family, the Lewises, who had been living in Ushuaia. Though the decision wasn’t John Lawrence’s, his letter back to the mission concludes:

We very much regret leaving Mr. Bartlett [another missionary] and his family, as we have now become thoroughly attached to each other. The past three years’ experience has been a season of unbroken happiness; we have been enabled to labour together in unity and godly love, but we sincerely trust the change will be conducive to the glory of God.

In Ushuaia, Lawrence soon became Thomas Bridges’ right-hand man and trusted friend. They served together for the next thirteen years, until Bridges resigned from the mission in 1886 and moved his family to a homestead further east.

In his absence, Bridges left John Lawrence in charge of the Ushuaia mission and recommended that he be ordained and appointed as director. Instead, the mission administrators named someone else as director, who traveled from England to take on the role.

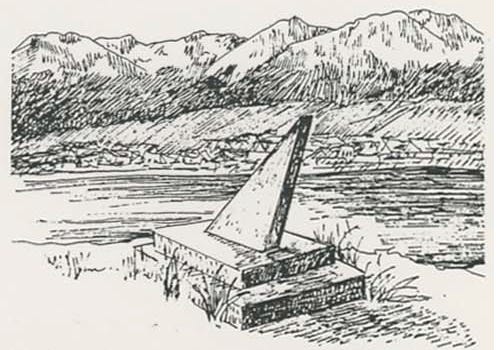

The new director moved the mission base to a different island, further south, to get away from the influence of the Argentinian government outpost that had been established on the other side of Ushuaia Bay. John Lawrence stayed behind with the remaining mission buildings and ministered to the Yahgan who didn’t want to relocate.

By then, however, the population of Yahgan had been decimated by waves of epidemics. Children, especially, had been hit hard, and Lawrence’s letters comments on how few children were left. Though the official school was closed, Lawrence continued to teach from his home until he was well advanced in years.

He stayed on in Ushuaia until 1900, when he moved to the homestead his children had established, several miles east of the Argentinian city. At that point, there were no Yahgan left living in Ushuaia, but the Lawrence homestead, Estancia Remolino, provided employment and a safe place to live for several indigenous families.

Lawrence continued his work for the mission from there, traveling to visit people and baptize as needed, until he officially retired in 1909. Even then, he continued teaching and encouraging the remaining Yahgan as he was able, and he oversaw the dismantling of the last mission building in Ushuaia in 1910.

As is evidenced in letters to his son, Martin, who studied in England for several years as a teenager, John Lawrence was an affectionate and dedicated father. According to family lore, he was particularly close to his younger daughter, Minnie May, who was a little spoiled by her parents. (She grew up to marry Thomas Bridges’ youngest son, Will, and became the mother of the line of Bridges who still live at the family farm of Harberton.)

In apparent contrast to the Bridges’, the Lawrences encouraged their children to embrace being Argentinian. While Mrs. Bridges returned to England for the final years of her life, and most of the Bridges’ children also lived in England for a time—so that one of Thomas Bridges’ sons volunteered to fight for England in WWI and several grandchildren enlisted to fight for England during WWII—two of John Lawrence’s three sons enlisted in the Argentinian army.

His sons Fred and Albert both married women of Yahgan descent, which was unusual at the time and somewhat frowned upon. His eldest son, Martin, married a local Italian-Argentinian woman and became a prominent businessman in Ushuaia. His sons ran various homesteads for several years, but the businesses never prospered. The various family lands were eventually appropriated by the Argentinian and Chilean governments.

Meanwhile, John Lawrence quietly passed away on Oct 18, 1932, at the age of 89.

Historian Arnoldo Canclini praises him with the following words, “His decision […] to stay at the mission reveals that, beyond his humility, he had a strong soul and a well-defined vocation. The way in which he persevered amidst a continuing decline shows he had the traits of a hero, […] hard to recognize and fully appreciate.”

Sources:

Arnoldo Canclini, Juan Lawrence: Primer maestro de Tierra del Fuego (Marymar, Buenos Aires: 1983)

South American Missionary Magazine, various volumes

Martin J. Lawrence, “Lawrence” in Ushuaia: 1884-1984, ed. Arnoldo Canclini (Hanis, Ushuaia: 1984)

Lucas Bridges, Uttermost Part of the Earth (New York: The Rookery Press, 2007)