The Martyrdom of Capt. Allen Gardiner

The (somewhat puzzling) death of a former navy officer and how it sparked a missions movement

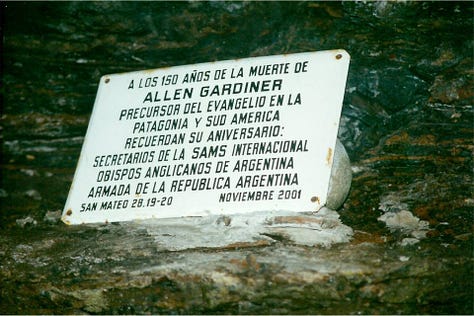

In 1852, news reached England of the death of seven missionaries on the shores of the southern tip of South America. The story appeared in newspapers and magazines throughout the country, scandalizing people who couldn’t understand why those men, including a respected former commander of the British Royal Navy, were willing to go to such a remote and difficult place to tell indigenous “savages” about Jesus—and even give their lives for the cause. Though there were questions about the soundness of certain decisions involved, they were hailed as heroes of faith and martyrs. For decades, Captain Allen Gardiner’s name inspired people to commit themselves to missions, either by becoming missionaries or by financially supporting missionaries through the South America Missionary Society.

In a published biography of Allen Gardiner, his chroniclers (who included his brother-in-law) described him this way:

With a frame of iron, and nerves which never flinched from fatigue or danger, he broke, with dauntless vehemence, through every difficulty which beset his path. He was always ready to meet the attacks of friends or foes, listening and replying to opposing arguments; but he was invariably steadfast to his own purpose. He never entered on a new enterprise without very much and earnest prayer for divine guidance. When visiting any of his friends, he generally found some path in the garden, which he paced like a quarter-deck, for hours each day, in the deepest study of God’s holy Word. Whatever might be the breakfast hour, he was always up an hour before, for prayer and the study of the Bible.

Allen Francis Gardiner was born in 1794, as the fifth son of parents who raised him in the Christian faith. From a young age, he was enthralled by the stories of travelers and adventurers and planned to become one himself by joining the navy. He attended the Royal Naval College, which at the time was an entry point for those who wanted to serve as officers in the navy despite lacking influential family connections1.

Early in his career, Gardiner distinguished himself during the War of 1812 by capturing an American ship. He moved up through the ranks until reaching the position of commander in 1826. During his time in the navy, he frequently traveled around the countries he visited, and he described his experiences of those places in his journals and sketchbooks. He also wrote about his increasing religious devotion—a change from his early years in the navy, which he describes as “walking in the broad way, hastening by rapid strides to the brink of eternal ruin.”

Gardiner married in 1823, and his wife, Julia, gave birth to one son, Allen W. Gardiner, and four daughters. One of his young daughters died, and, less than a year later, Julia Gardiner died in 1834. The death of his wife and daughter strengthened his resolve to pursue missions.

Gardiner left the navy and went to South Africa first, in 1834, establishing the first missionary outpost among the Zulu of the area of Port Natal.2 In the end, however, he decided there were enough other missionaries in South Africa that his efforts weren’t needed, and he left when a war between the Zulu and Boer settlers was eminent.

Allen Gardiner married again, and his second wife, Elizabeth Marsh, accompanied him first to South Africa, then to South America and the Falkland Islands, where he sought to establish a home base for his missions work. (His wife, however, stayed with the children in a city while he went on ahead to explore the frontier lands for missions.)

In south-central Chile, which Gardiner had gotten to know a little in his travels in the navy, he asked various local Mapuche chiefs (through an interpreter) for permission to live there with his family, learn their language, and tell them about the God who’d sent him. The Mapuche, however, refused: they were reluctant to host a white outsider, as they’d been in conflict with Spaniards and Spanish-speaking Chileans for the last three centuries, and the whole region was dotted with fortresses to keep them in check. Gardiner also faced opposition from some Catholic missionaries.3

He then turned his attention further south, toward Patagonia, which was then an undefined region beyond the nebulous southern borders of either Chile or Argentina. His idea was to establish a base of operations in the Falkland Islands, under British rule, and travel sporadically to the region with European sealers and whale-hunters, then bring back a few Tehuelche at a time to the Falkland islands, so he and other missionaries could learn the language before moving to Patagonia to live among the indigenous people there.

Up until this point, Gardiner’s work was largely self-funded, but he now realized he needed wider support for himself and potential future teammates. He went back to England and tried to convince an established missions agency to sponsor his vision among the Tehuelche. When several missions agencies declined, saying the location was too remote and the logistics too difficult, Gardiner founded his own agency, which he named the Patagonia Mission Society (later renamed the South America Mission Society).

When Gardiner made it back to Patagonia, however, circumstances had changed significantly for a local chief who had previously approved Gardiner’s settling there. The situation was no longer favorable, and Gardiner returned to England with his family.

At this point, Gardiner could easily have given up, and many people encouraged him to do so. Instead, he eventually decided to pursue missions Tierra del Fuego, at the very southern extreme of the continent. Specifically, among the Yahgan, who Charles Darwin had described as “miserable, degraded savages.”

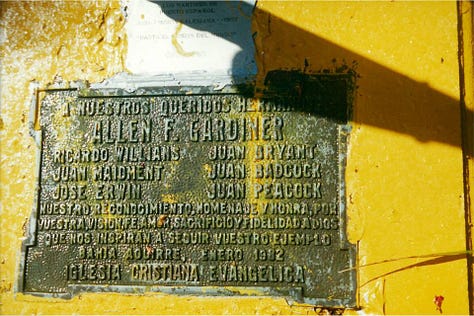

In September 1850, Gardiner set sail for Tierra del Fuego with Richard Williams (a surgeon), John Maidment (a former waiter “whose piety, trustworthiness, humility, faith, and hardihood, rendered him fit for such a work”), Joseph Erwin (a ship carpenter who returned for a second voyage with Allen Gardiner, because “being with Captain Gardiner was like a heaven on earth, he was such a man of prayer”), John Pearce, John Badcock, and John Bryant (three Cornish fishermen “of high character and simple piety, who had worked together as fishermen and lived together as Christians”). The expedition was largely funded by a woman named Jane Cook, who gave £1000 (the equivalent of about £170,000 today).

The plan Gardiner had devised was that the missionaries would build themselves a shelter on shore but keep their provisions on their two small boats, since Gardiner’s previous exploration had taught him the Yahgan were used to helping themselves. None of the missionaries could communicate with the Yahgan, but Gardiner intended to sail along the Beagle Channel until he found a man known as Jemmy Button, who had spent some time in England as a teenager and could serve as a translator.

From the start, mishaps plagued the group. The first being that they accidentally left their gunpowder on board the ship that dropped them off, so they weren’t able to hunt the plentiful ducks, geese, seals, and penguins as planned. The next was that the freshwater fish Gardiner had seen on his previous trip weren’t as abundant in a different season. One of the boats in which they kept their provisions had a leak, and when they tried to bring it onto land for repairs, it crashed on some rocks and was destroyed. They lost in a storm the two small dinghies they’d planned to use for boarding their boats, so they had to get into the (ice-cold) water and swim every time they got in or out of their one remaining operable boat.

Also, there was tension between the missionaries and the Yahgan almost from their first encounter.

Before the departure of the ship that dropped them off, Allen Gardiner wrote in a letter to the missions committee, “[The Yahgan’s] rudeness, and pertinacious endeavor to force a way into the tents, and to purloin our things, at length became so systematic and resolute, that it was not possible to retain our position without resorting to force, from which, of course, we refrained.” Gardiner and the other missionaries were on constant alert for an attack. A large gathering of Yahgan made them retreat quickly to their boat, and they assumed the absence of any Yahgan meant they were gathering forces elsewhere, planning an attack.

Thomas Bridges wrote later of the Yahgan perspective of the missionaries:

These Indians who, in reality, are eminently sociable, mix with familiarity in any meeting, go with great liberty into any hut, and live in a perfect equality, could not comprehend the authoritarian, disagreeable, and suspicious attitudes of their strange visitors. Seeing all that these strangers brought along, they were irritated by the obvious intention of the newcomers to keep all those coveted treasures for themselves. Moreover, the missionaries kept to themselves, as a group of bachelors. This had great importance for the Indians, who were all married and had never heard of a group of men living without women. The Fuegians therefore believed, entirely naturally, by intuition, that the missionaries had hostile motives.

Writing about the Yahgan tendency to help themselves to any food supply, which he said the missionaries should have known about from Darwin’s writing and from Gardiner’s previous experience, Thomas Bridges concluded:

In this circumstance, there were only two ways of staying in the Fuegian territory: […] from the beginning declare war on the Indians, kill several, and then live in isolation in their country—or share with good grace all their supplies with the Fuegians, adopt the mode of life of the Indians, and live among them as equals.”

Unfortunately, Allen Gardiner and the other missionaries chose the first route.4

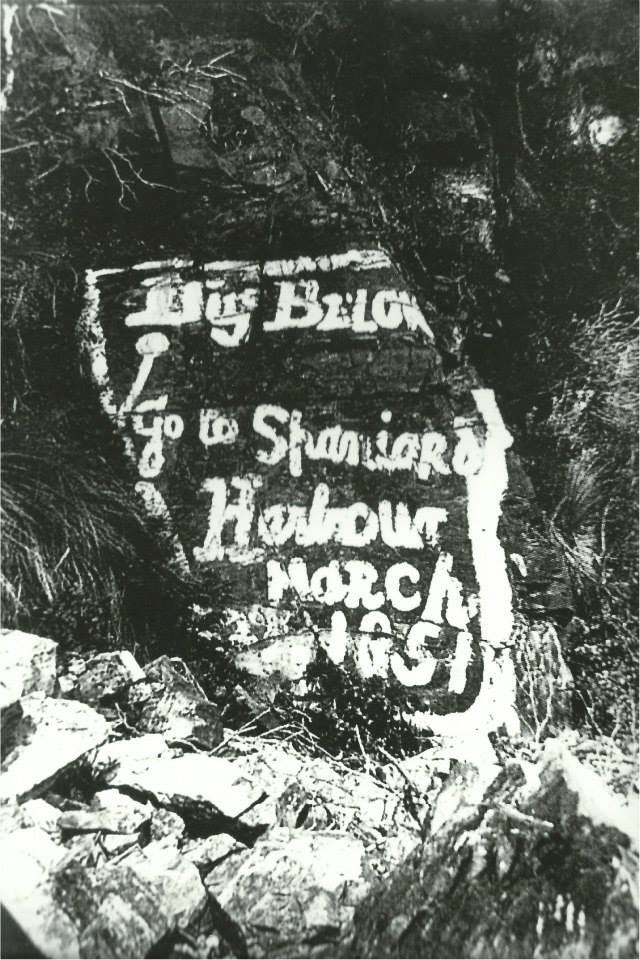

Partly to escape the Yaghan, the missionaries crossed the Beagle Channel to a place called Spaniard Harbor, which was so difficult to navigate to that the Yahgan didn’t go there. The missionaries hid some of their provisions in a cavern and set up camp to wait for the shipment of new provisions from the missions committee, which they expected in June, or for a passing ship to take them back to the Falklands.

Later sailors would question why they themselves didn’t set sail for the Falklands, or to another established settlement on the eastern end of the Beagle Channel. It’s possible they didn’t think their one remaining boat was in good enough shape to get them there, or they may already have been feeling weak. In any case, neither of the missionaries’ journals that survived recorded any consideration of sailing away.

By March, the first member of the team was sick with scurvy. They tried a few ingenious ways to catch and scavenge for food, and they were able to catch some fish with the nets that they’d brought, but the nets broke in late May and (after being repaired) again in late June—and that time, the damage was too extensive to repair. Though earlier the men had bartered with the Yahgan for fish, by this point they were avoiding the Yahgan to such a degree that it seems no one thought to ask them for help.

As the situation was becoming more dire, Gardiner wrote in his journal:

Grant, O Lord, that we may be instrumental in commencing this great and blessed work; but shouldst thou see fit in Thy providence to hedge up our way, and that we should even languish and die here, I beseech Thee to raise up others, and to send forth labourers into this harvest. Let it be seen, for the manifestation of Thy glory and grace, that nothing is too hard for Thee; and hasten the day when the knowledge of the Lord Jesus Christ shall be manifested, not here only, but throughout every nation, and people, and tribe, and prayers and praise shall ascend, and a pure offering from the hearts of multitudes who are now sitting in darkness.

For a reason that’s unclear, but may have to do with conflict between Gardiner and Williams (whose journals records some sharp criticisms of Gardiner’s attitude and his unilateral decision-making), the group split into two camps, about a mile and a half distant from each other. At first the healthy members of the group traveled between the two sites, but as the team weakened, that became impossible.

The first member of the team to die was John Badcock, one of the Cornish fishermen, on July 3. By August 14, Allen Gardiner was too weak to get out of bed and had to depend on John Maidment to gather fuel and food. One by one, the others died, and Allen Gardiner’s last words in his journal are dated Sept. 6, 1851. At that point, he hadn’t eaten for five days.

During the eight and a half months the missionaries were in Tierra del Fuego, at least three ships had been instructed to take them supplies, but one was shipwrecked, another veered off course by a storm, and another didn’t stop, for some reason. On Oct. 22, a Captain Smyley made a special trip to find the missionaries, and when he landed in the middle of a storm, he found three bodies and “books, papers, medicine, clothing, and tools [strewn] along the beach.” He and his crew only had time to bury one of the bodies before the storm blew their ship back out to sea.

On January 19th, 1852, another ship arrived from the Falkland Islands. They found the rest of the remains of the missionaries and their books and papers. They buried the bodies, conducted a funeral service, and took the papers back to England.

The chronicles of Allen Gardiner’s story drew this conclusion of the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the missionaries’ deaths:

All these regretful thoughts give place to wonder and admiration, and thankfulness for the grace of God, which was so strikingly displayed in not one alone, but all, so that they were examples to each other of patient endurance, and unfailing faith. […] Moreover, through the marvelous peace and calmness and steadfast resolution [of Allen Gardiner], and the wonderful preservation of the manuscripts, when no one of the party survived to guard them. It is our privilege to know more of their dying thoughts and last words than can often be attained when one is in close attendance in a death chamber.

Gardiner’s chroniclers also concluded, “It would seem as if nothing short of so startling an event could rouse the Christian world into an interest for the heathen tribes of South America.”

When the news reached England, in April 1852, reports were published in the London Times and featured in other newspapers and magazines throughout the country. Though there were plenty of people who questioned the judgment of the missionaries, a small group of Gardiner’s admirers, including Rev. George Pakenham Despard (Thomas Bridges’ adopted father) and John Marsh (Gardiner’s brother-in-law) decided that the seven men’s deaths would not be in vain. They proclaimed them martyrs and traveled throughout England and Scotland raising funds in their memory, reading excerpts from Gardiner and Williams’ diaries.

Funds went toward three successive ships for the Patagonia Missionary Society/South America Mission Society, named the Allen Gardiner in his honor. Inspired by Gardiner’s example, people also volunteered to become missionaries—including Rev. Despard, who took his family with him to the Falkland Islands, including 13-year-old Thomas Bridges, who devoted the rest of his life to work among the Yahgan. Allen Gardiner’s only son, Allen W. Gardiner, went with that same group and later settled in mainland Chile to continue his father’s early work among the Mapuche.

The Church of England officially commemorates Allen Gardiner on September 6, the day of his death. Because of his zeal, example, and visionary plan for missions outlined in a memorandum composed shortly before his death, Gardiner is considered the father of Anglicanism in South America. The Anglican church continues to be vibrant there, especially in Chile5, and Gardiner’s memory is still honored for his sacrifice and his dedication to telling others about God in South America.

SOURCES

Allen Francis Gardiner, A Visit to the Indians on the Frontiers of Chili (London: Seeley and Burnside, 1840)

Allen Francis Gardiner, Narrative of a Journey to the Zoolu Country, in South Africa (London: William Crofts, 1836)

John Marsh and Waite H. Stirling, The Story of Commander Allen Gardiner, R.N., With Sketches of Missionary Work in South America (London: Nisbet & Co., 1877)

Anne Chapman, “Allen F. Gardiner Searches for Heathens and Finds the Yamana” in European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010)

Diego Pacheco Torrealba, Allen Gardiner: El legado del anglicanismo en Sudamérica (Viña del Mar, Chile: Mediador Ediciones, 2018)

Two of Jane Austen’s brothers attended that same academy a few decades before Allen Gardiner. Both Francis and Charles Austen went on to become admirals.

He published an account of his experiences in Narrative of a Journey to the Zoolu Country, in South Africa, an evangelical adventure story that details several brushes with death in unfamiliar territory and among native people who weren’t always friendly toward outsiders. The book is interspersed with prayers and poems, sometimes composed on horseback.

Interestingly, the Mapuche are the people group my parents worked with as missionary-linguists when I was a kid.

In the same passage, Bridges says that Gardiner group “killed one or several Indians,” though this isn’t recorded in either Allen Gardiner’s published journal or the published journal of Richard Williams. It does fit, however, with the fear with which Gardiner’s group regarded the Yahgan, and it could explain why the missionaries relocated to an isolated bay where there weren’t any Yahgan.

I personally experienced this as a child, through the Anglican church my family attended in Temuco, Chile, when I was a kid. I’ve also gotten to know a number of Chilean Anglicans as an adult, including the author of a book titled (in Spanish) Allen Gardiner: The Legacy of Anglicanism in South America.

Two things stood out to me in this account:

Long periods in the garden praying and reflecting on Scripture

The major cultural misunderstanding of what-is-mine-is-yours. Reciprocity between Gardiner’s men and the Yaghan might have changed the story.