The Traditional Yahgan "School"

The chiexaus and kina ceremonies ushered Yahgan youths into adulthood and became a symbol of their culture

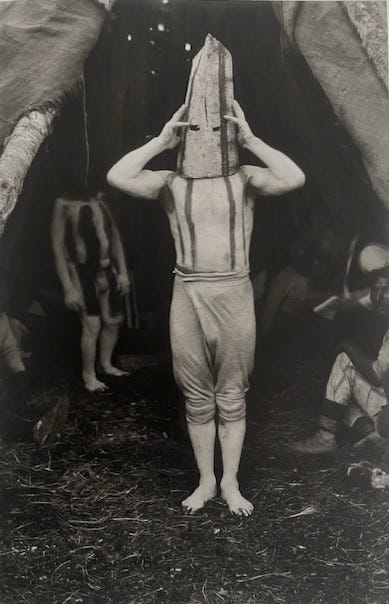

One of the most striking visual elements of indigenous Fuegian culture is men painted and masked to represent spirits as part of the secret male initiation ceremony, known as the kina among the Yahgan.

Prior to this came the chiexaus ceremony, the initiation rite into adulthood for both boys and girls who had passed through puberty.

Both of these ceremonies are essential for understanding traditional Yahgan culture as it was before the incursion of European, Argentinian, and Chilean outsiders.

The chiexaus ceremony was a pivotal part of teaching Yahgan youths how to behave properly and how to fulfill their expected roles in the community. It marked the transition point from a carefree childhood with few obligations (for boys, anyway) into the responsibilities of adulthood.

There was a lot of secrecy involved. Those who weren’t yet initiated weren’t allowed near the building where the teaching took place, and graduates weren’t allowed to discuss what they’d experienced with the uninitiated. This meant that the early missionaries and scientists didn’t know much about the ceremonies.

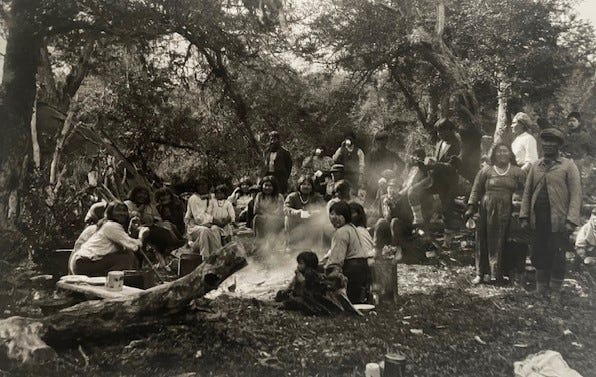

It wasn’t until decades later that certain Yahgan were willing to trust outsiders enough to explain the ritual. Then, in the 1920s, the dwindling community agreed to let anthropologist Martin Gusinde participate in the ceremony, record notes, and photograph certain aspects. Others have since published their memories and perceptions of the ceremonies for the benefit of outsiders and posterity.

One woman, Lakutaia le kipa, known in Spanish as Rosa Yagán, recalled being “kidnapped” at night while she was on the beach collecting rocks. Her “captors” were covered in paint and singing. She was badly frightened and tried to fight them off. At the door of a large, oblong bark-and-branch building, they covered her with a blanket so that she couldn’t see, and they put out the fire with water. She heard people stomping their bare feet against the ground.

When they took the blanket off her head, she saw adults wearing normal clothes though their faces, hands, and feet were painted white. The building (known as the chiexaus because it was built specifically for the ceremony) was painted red, white, and black on the inside. Everyone was seated and singing.

The girl slept in the building for the duration of the ceremony. Her godmother painted her face each new day, sometimes with dashes and sometimes with dots, to mark her as an initiate.

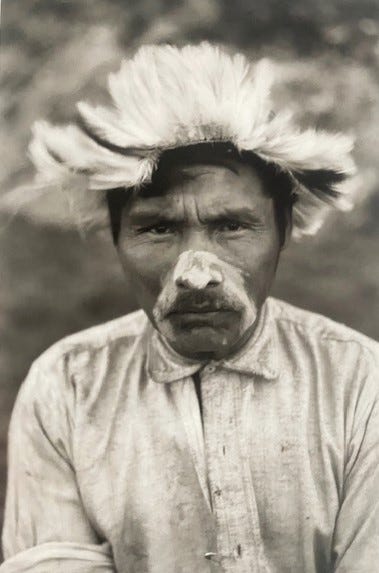

She received a straw made out of a bird bone (for drinking water), a pole (to scratch herself with, since initiates weren’t supposed to scratch with their fingernails), a basket woven by her godmother, and a crown of white bird feathers.

She and the other initiates had to work all day gathering wood or doing other tasks, under the strict supervision of the adults. They also instructed her in the Yahgan moral code: how to mind her own business, to always share food with others, to not steal, to respect her elders and do whatever she could to help them.1

The initiates’ self-discipline was also put to the test. They were required to fast or were given minimal amounts of food while the adults around them feasted. They weren’t allowed to laugh, even when the adults purposefully told funny stories. They had to stay crouched down, in an uncomfortable position, with eyes lowered. They were only allowed a few hours of sleep.

Because of the hardships involved, teenagers feared the ceremony, and the adults strictly enforced the rules. Initiates often lost weight and grew weak over the course of the ceremony.

Meanwhile, the adults entertained themselves with games and dancing. They sang secret songs, ones only sung in the chiexaus. They acted out theatrical presentations to teach morals and told stories about the creation of the world, the arrival of the first humans, the instructions to their descendants, and other cultural traditions.

The ceremony could last from six weeks to three months, depending on the progress of the pupils. However, the ones that took place in the 1920s, like the one in which Lakutaia le kipa participated, lasted a week to ten days because there were fewer students.

Partly a school for moral and ethical training, partly a training camp for some of the hardships of adult life, the chiexaus didn’t happen at regular intervals. It was opportunistic, when there was a significant enough group of people gathered in one place, with sufficient food supply to last a while—if there was a beached whale, for example, or a large funeral involving several different families. Before the chiexaus in 1920, the most recent one took place in 1910 or 1911.

Initiates were usually between 12 and 17 years old, and traditionally there could be between twelve and twenty of them participating. A master of ceremonies was in charge of the teaching, an “inspector” made sure tradition was followed, and a “guard” to make sure the pupils behaved and no one came close who wasn’t supposed to. Other adult members of the community participated as well, as each initiate had between one and three godparents to personally oversee their instruction.

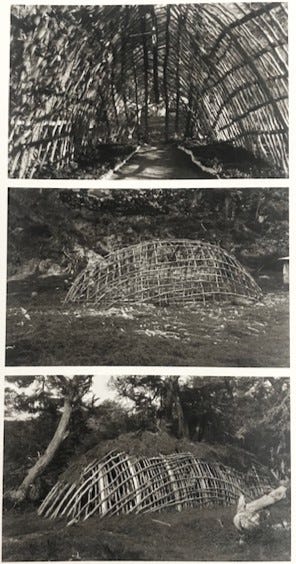

After the ceremony, graduates were considered adults, full members of the society, and were allowed to marry and form their own families. The chiexaus building was mostly dismantled, although it might be used again for the next ceremony.

The final chiexaus was partially celebrated in 1935. When a boy died while collecting firewood, Chilean authorities prohibited the ceremony, saying more people would die if it was carried on.

Cristina Calderón, widely known as “the last Yahgan,”2 was too young to participate, but since older members of the community knew it would be the last time a chiexaus was celebrated, they took her inside the secret building so she could at least see it and hear what happened during the ceremony.

The prohibition of the ceremony meant that Lakutaia le kipa was part of the final group of initiates of the Yahgan chiexaus.

The even more secretive kina was a ceremony that was, for many years, confused with the chiexaus by outsiders.

This ceremony, however, was an initiation rite specifically for men. To be eligible for participation, males had to successfully go through the chiexaus twice. It was even more occasional than the chiexaus: before 1922, the most recent kina had occurred thirty years previous. This ceremony was so secret, people almost never said the word “kina.”

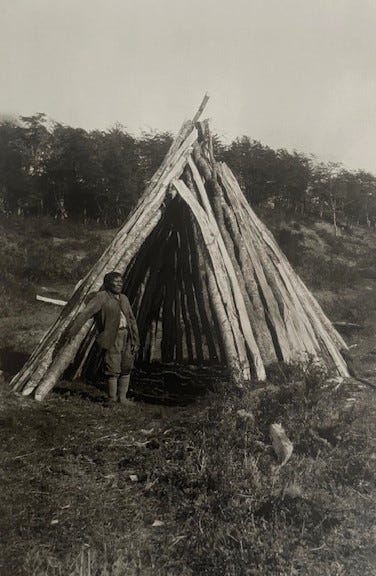

Similar to the chiexaus, the building used for a kina was also built specifically for the ceremony, and the building took on the name of the ceremony. The building was also much larger than the average Yahgan house, but it was conical in shape.

The most influential elders organized the kina, which was overseen by a chief chosen especially for the occasion. Each initiate had a godfather who watched out for the young man. As in a chiexaus, initiates experienced physical hardship and little food, which was meant to make them more susceptible to the teachings.

The kina might last a few days or up to two weeks, during which time the men involved—both the initiates and their instructors—weren’t allowed to have any contact with women.

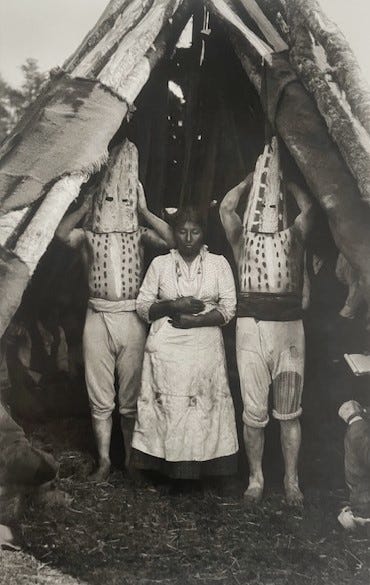

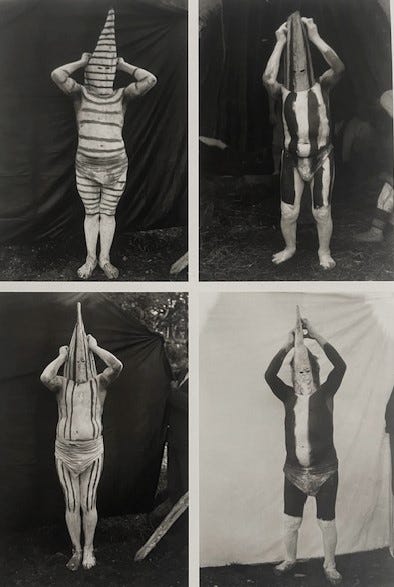

The main distinctive of the kina was that men donned tall masks made out of tree bark, painted red and white. In this form, they were meant to represent spirits for the purpose of scaring the women and punishing those who were disobedient or lazy. The women apparently believed the deception, much to the amusement of the men.

According to anthropologist Martin Gusinde, who was allowed to participate in the ceremony in 1922, the main purpose of the kina was to communicate “the ways of dominating women so that they submit in everything to the will of the men and don’t try to dominate them. […] Men are supposed to inspire in women a desire for obedience, respect, and submission.”

He said, “The women were told that spirits would descend from above in visible form, come out of the building, and show themselves to everyone. But such spirits were simply the same men who, completely painted and masked, left the building dancing, yelling, and scaring the weaker sex.”

According to Yahgan legend, “In ancient times, women were the ones who ruled and participated in the kina games and apparition of spirits to keep men subjugated. One day, the Sun, who was an excellent hunter in those days, discovered the deception; he warned the other men right away, and they conspired against the women, killing all of them except for the very young girls. Since that time, men have been in charge of these ceremonies, keeping careful guard lest women take back the power and the authority.”

Some have taken this legend as evidence that the Yahgan were originally matriarchal, though this is contested.

Martin Gusinde described the kina ceremony as exactly like the hain of the Selk’nam, the Yahgans’ indigenous neighbors to the north. Gusinde, who participated in the ceremonies of both groups, took this as evidence that the Selk’nam tradition had been incorporated into Yahgan culture, even though the two groups were linguistically and ethnically separate.

The shape of the Selk’nam masks is different (not as tall, more horizontal) and more varied, so that the ceremony participants can be distinguished by sight, but the body paint and otherworldly appearance means the photographs are similar enough to be easily confused by outsiders.

These photographs now function as the most easily recognizable depictions of the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego, though they are sometimes used in a way that highlights the “otherness” of the “primitive” people.

In any case, the kina was one of the most distinctive and important parts of Yahgan culture, with traditions being handed down from one generation to the next, uninterrupted for centuries, until the arrival of outside governments who imposed their own rules on the ancient culture.

Sources:

Víctor Vargas Filgueira, Mi sangre yagán (My Yahgan Blood) (La Plata, Argentina: La Flor Azul, 2021).

Martin Gusinde: El espíritu de los hombres de Tierra del Fuego (The Spirit of the People of Tierra del Fuego, photo book), ed. Christine Barthe and Xavier Barral (Paris: Éditions Xavier Barral, 2015)

Martin Gusinde, Expedición a Tierra del Fuego (Expedition to Tierra del Fuego) (Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria, 1968).

Luis Abel Orquera and Ernesto Luis Piana, La vida material y social de los yámana (The Material and Social Life of the Yamana) (Ushuaia, Argentina: Ediciones Monte Olivia, 2015)

Patricia Stambuk, Rosa Yagán: Lakutaia le kipa (Santiago de Chile: Pehuén, 2011)

“Yahgan Explorers and Settlers: 10,000 years of Southern Tierra del Fuego Archipelago History,” permanent museum exhibit script, Museo Territorial Yagan Usi–Martín González Calderón, Puerto Williams, Chile. https://www.museoyaganusi.gob.cl/

Cristina Zárraga, Cristina Calderón: Memorias de mi abuela yagán (Memories of My Yahgan Grandmother) (Punta Arenas: Ediciones Pix, 2016)

Anthropologist Martin Gusinde said his godparents instructed him in practical and moral matters such as how to treat others, how to care for a wife and children (ironic, in the case of Gusinde, who was a Catholic priest), how to make weapons, and how to fish and hunt. Both male and female teenagers participated in the chiexaus, but the practical instructions they received were different, befitting them for different roles in the community.

Hi, I just wanted to say that, as someone who is also really interested in and has been researching 19th century Tierra del Fuego, the Yahgans, and their language, it's cool to see well-written, well-researched pieces on the internet about a pretty niche topic! Best of luck with your book!