One of the most colorful characters in the history of Tierra del Fuego is Julio Popper. No one who visits the area leaves without hearing about him. He is, at once, admired as the organizing genius of a mining empire—complete with its own army, coin mint, and postal service—and (unfairly) reviled for the genocide of indigenous people. Stories about him are the stuff of legend, like the time he put sticks in the hands of stuffed mannequins in order to make his troops seem more numerous than they were. He was backed by friends in the upper echelons of power in the federal government of Argentina, and he got several governors fired after their open conflicts with him. Then he died, suddenly, in Buenos Aires—at age 35.

Iuliu Popper was born to an Ashkenazi Jewish family in Bucharest in 1857. At that time, Jews were barred from getting a university education in Romania, so when he was fifteen, he went to Paris to study and became a mining engineer. He also took classes at the Sorbonne in physics, chemistry, meteorology, geology, geography, and ethnography. He spoke five languages fluently. Records of the day describe him as tall, blond, blue-eyed, remarkably handsome and impeccably mannered.

Upon completing his studies, he traveled to Constantinople, then to Egypt (where he worked on the Suez Canal), throughout the Middle East, India, Japan, and China. He visited Siberia, then traveled across Alaska and Canada to reach mainland United States. He was hired to work on canals and city planning in New Orleans. He was instrumental in planning the design of modern Havana, Cuba. He worked as a reporter in Mexico.

All before the age of 29.

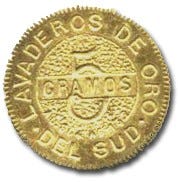

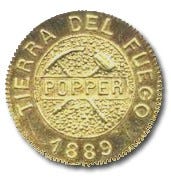

When he arrived in Buenos Aires, he very quickly became friends with the government elite—probably through Masonic Lodge connections. After gold was discovered on the Strait of Magellan, he organized a group of prospectors to head south with him. Then he created a mining company: Compañía de Lavaderos de Oro del Sud (Company of Gold Washers of the South). Through the influence of his powerful friends, he obtained a sizable land grant in Tierra del Fuego for the purposes of extracting gold.

On the northeast side of the main island of Tierra del Fuego, he set up his principal mining establishment: El Páramo. He built machines (including two he patented) to separate gold from sand, and at one point his operation was producing a kilo (2.2 lbs) of gold per day. More than 100 men, mostly Croatian immigrants, lived and worked at his mining camp. His younger brother Máximo was his chief of police.

Argentina at this time was a young country. It declared its independence from Spain in 1816, but it was plagued by civil wars until 1861. It was very eager to establish its place in the world, and the government instituted a policy of actively encouraging European immigration. Because of this, the population quadrupled from 1869 to 1914, and its economy grew by leaps and bounds. By 1908, it was the seventh wealthiest nation in the world. President Roca’s Conquest of the Desert tripled the country’s territory.1

Popper’s men were the first white people to explore beyond the coasts of the island of Tierra del Fuego, and his prospecting expedition ran into skirmishes with the indigenous Selk’nam (also called Ona), as that part of the island was their homeland. Once, when Popper’s men were hunting guanaco, the Selk’nam shot at them with arrows. Popper’s men “returned the compliment” with their rifles. Popper’s group suffered no casualties in these skirmishes, but they killed at least two Selk’nam on that occasion—and that happened about every day.

A photograph showing the aftermath of one of these skirmishes was published on the cover of Popper’s report of his expedition. In the photograph, the tall, straight-backed, uniformed Popper proudly stares off across the horizon, rifle in hand, while three of his kneeling men keep their rifles trained on the ridge of a nearby hill. At Popper’s feet is the naked corpse of an indigenous man, arms open to the sky as if he was crucified, bow and arrows still in his hand.2

This photograph is the reason Popper is infamous as a ringleader of genocide. I’ve seen it reproduced in a mural on the street in Ushuaia, printed in museum materials, and published on webpage after webpage. It has come to symbolize the violence and the cruelty of the national government, the foreign settlers, and the estancieros toward the indigenous people.3

But actually, the vehemence against Popper as an “Indian hunter” is misplaced. The reality is that Popper spoke out against the ruthless, indiscriminate killing of indigenous people. The report of his expedition shows curiosity toward the Selk’nam and frustration over his failed attempts to communicate with them. He records multiple interactions of trying to convince the Selk’nam he didn’t intend them any harm. His description of them is, yes, patronizing—but he also found things to admire in their strength of will and endurance of hardship. He used killing force to protect himself and his men, but there are no records to indicate he ever sought out Selk’nam for the purpose of killing them.

His caption for that photo, within his report, was “Lower your gaze.” An accompanying photo was captioned “Dead man on the field of honor.”

Popper actually sought—and won—government approval for an indigenous refuge in the northern part of the island of Tierra del Fuego, where the Selk’nam could be safe from the encroaching violence. The Selk’nam were promised their own pieces of land, their own homes, and food for six months as they were getting established, all funded by Popper’s mining company.

Some of Julio Popper’s other proposals included setting up a telegraph line to reach the southern tip of Argentina and establishing a maritime city on the eastern side of the island, which he wanted to name Atlanta.

Because of his wealth and ambition, he was attacked by Chilean raiding parties, and he galloped into battle, sword drawn, proclaiming he was doing so in defense of his adopted country, Argentina. But his proposals and his power also put him into direct and public conflict with two different governors of the Argentinian territory of Tierra del Fuego. Both of those governors were subsequently fired by the federal government.

According to one historian:

Without a doubt, he was a megalomaniac and over-the-top, with a penchant for the picturesque that clouded his merits. But […] he was a genuine defender of his adopted country. Regardless of the fact that he was simultaneously defending his personal interests, […] he lived in a time during which defending the country’s sovereignty [against Chile] earned a person much respect.4

Popper never completed his many proposed projects. In June of 1893, he was found in his lavish Buenos Aires apartment, lying on a guanaco rug on the floor of his bedroom, with the sheets turned back on his bed. Rumors abounded—and still proliferate—about his sudden death. Was he killed by other gold miners? The ghost of a murdered indigenous person? Did one of the governors he’d ousted exact vengeance? Did someone in government feel he was becoming too powerful? All of those make for a good story, but an autopsy indicated it was heart failure, from natural causes.

He was 35, and he had lived in Argentina only eight years. But many of the names he designated for places in Tierra del Fuego have remained in use, and he left an indelible mark on the province—for better or for worse.

Sources:

Arnoldo Canclini, Tierra del Fuego: De la prehistoria a la provincia (Buenos Aires: Editorial Dunken, 2007), 127-130.

Rae Natalie Prosser Goodall, Tierra del Fuego (Ushuaia: Ediciones Shanamaiim, 1979), 103.

Chris Moss, Patagonia: A Cultural History (Oxford: Signal Books, 2008), 192-194.

Julio Popper, Atlanta: Proyecto para la fundación de un pueblo marítimo en Tierra del Fuego y otros escritos (Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 2003).

This “conquest” was warfare against the indigenous people who previously inhabited the land, with the express purpose of destroying those cultures so that European immigrants could set up farmland. There were mass executions and forced sterilizations. More than 1000 Mapuche people were killed, and at least 15,000 were displaced. Many people were enslaved. The Argentinian government explicitly considered indigenous people less human than those of European descent and so argued that they didn’t deserve the same rights as white people.

I’m not reproducing the photo here because of the trauma that’s associated with it, but those who are curious can see it here.

The estancieros (ranchers), who claimed enormous tracts of land and set up sheep farms in what had been Selk’nam territory, got angry at the Selk’nam for raiding their sheep and destroying their fences. They paid their employees to kill the Selk’nam: a British pound sterling per ear. According to one source, the henchmen were paid more for killing women, to make sure there wouldn’t be another generation. The worst of the estancieros’ killers was the Scotsman Alexander MacLennan, known as “Chancho Colorado” (Red Pig). He wiped out entire villages and massacred dozens, simply because they were Selk’nam.

This is from Arnoldo Canclini, Tierra del Fuego: De la prehistoria a la provincia, p. 130 (translation mine).