One of the most striking aspects of traditional Yahgan culture was the use of face and body paint. Early European explorers who encountered the group always mentioned it in their written descriptions. The missionaries condemned it as a heathen practice. Later anthropologists reveled in photographing it. When Yahgan are represented today in art or murals, it’s always with face or body paint.

It’s easy to grasp hold of this clear, visual distinctive to “other” an indigenous culture without understanding the practice. But there’s beauty and meaning in the particulars. Here’s what face and body paint meant for the Yahgan.

The Yahgan traditionally used face and body paint to signal something about a person—to mark them as a bride or groom, for example, or so everyone they encountered would know they were in mourning. A young woman would get her face painted when she had her first menstruation, and someone planning a visit would get his or her face painted to honor the person they intended to visit.1

Face and body paint could also be used for “everyday” purposes of ornamentation—for example, a mother might paint her children’s faces just for fun (probably similar to the way I put a hairbow on my infant daughter).

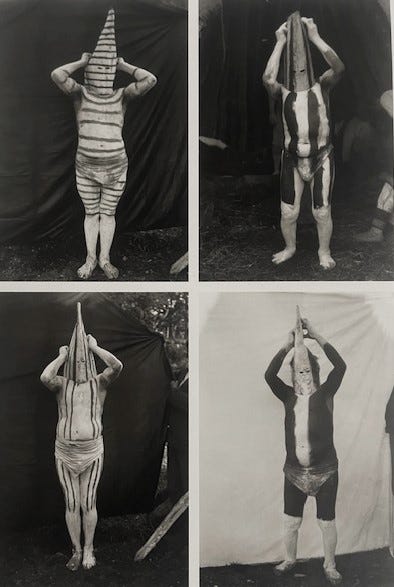

The secret “school” of the chiexaus and the kina male initiation ceremony used body paint for a very specific purpose. During the chiexaus ceremonies, certain colors and patterns of face paint were part of what identified the youths being initiated, their godparents (who were in charge of keeping the teens in line), and the teachers. The kina involved the most elaborate type of full-body painting, connected to special masks that men wore to disguise themselves as spirits and scare the community’s women and the initiated youths into submission.

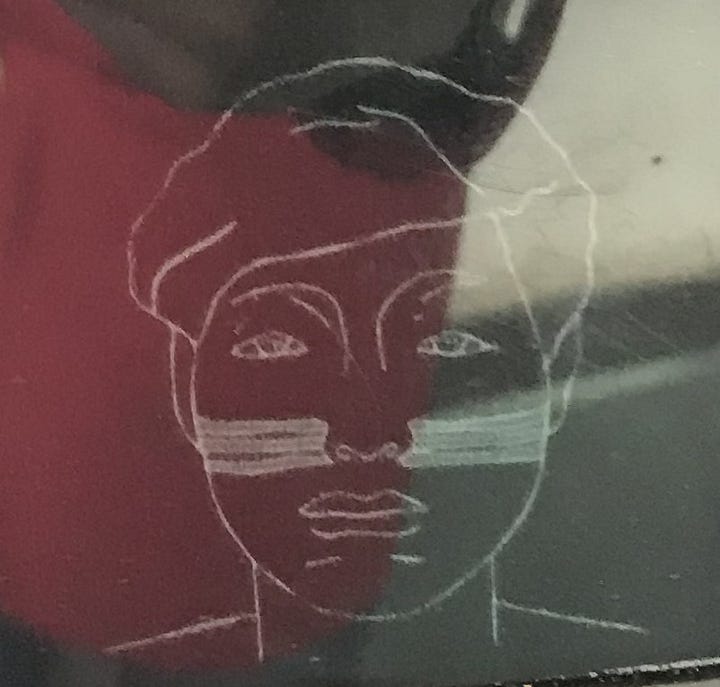

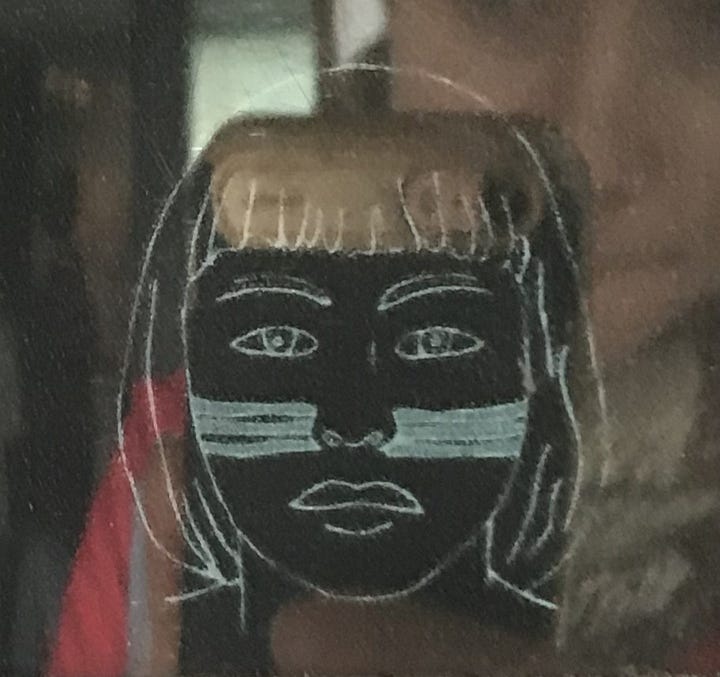

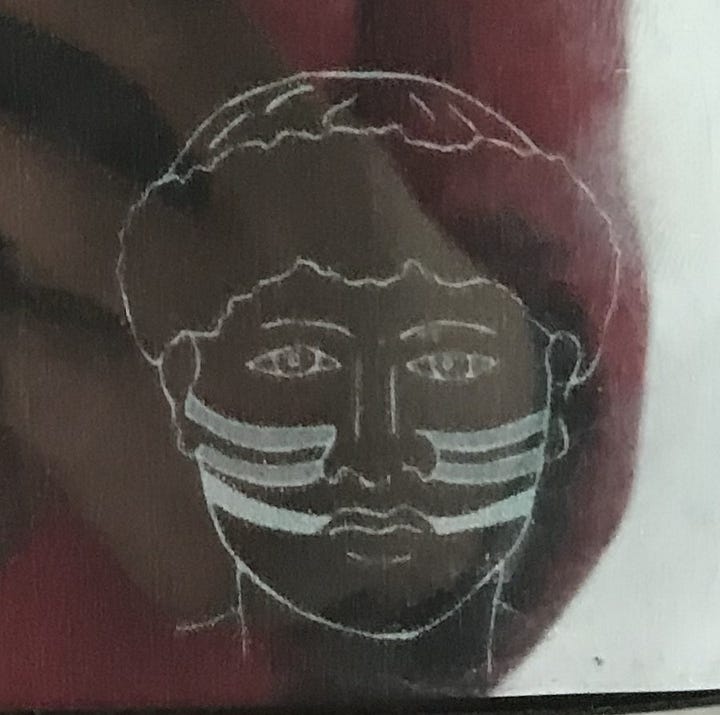

Yahgan face paint consisted of three colors: red, black, and white. White paint was made using clay, ashes, or lime (from rocks on the north of Navarino Island). Red paint came from clay or blood. Black paint came from charcoal.

Charcoal was always readily available from the fires the Yahgan carried with them in their canoes, but the materials for making white and red paint were carried from place to place, stored in bags made from animal hide. When someone needed paint, they mixed pigments with water, saliva, animal grease, or fish oil in either their hands or a mussel shell. Sometimes they cooked or baked the pigments to strengthen the color.

The paint was applied by someone else, using fingers or sticks—although mirrors were adopted for the purpose of self-painting once Europeans introduced that technology.

The code of the face paint was communicated through color and pattern: usually a combination of dots and dashes running vertically or horizontally.

For example, a bride and groom were marked using three red horizontal red lines that stretched from the edge of the nostril to the earlobe. A girl experiencing her first menstruation announced the fact with vertical lines in red paint under her eyes.

Unfortunately, the code has mostly been lost as the tradition faded. Thomas Bridges referenced encountering someone whose face was painted to show he was seeking revenge for the murder of a relative, but Bridges didn’t record a description of the pattern or color of the painted design.

The patterns most clearly recorded and remembered are, sadly, the ones for mourning the death of a loved one. This type of face paint shows up frequently in the photographs of the Europeans who studied the Yahgan in the 1880s through 1920s. During this period, the numbers of the Yahgan dwindled from about a thousand to fewer than one hundred, and everyone was almost constantly in mourning.

According to one anthropologist, “The act of getting painted seems to have been more significant than the kind of design that was worn. [The paintings] were a means of expression of pain for the loss and of sympathy for the relatives, and a way of communicating the news to other persons.”

As more Yahgan passed away, however, the depth and richness of their traditions, including the full range of meanings of face and body paint, were lost. The best we can do now is to honor the past as it has been handed down and as it is remembered by the Yahgan who still live in the area.

Sources:

Luis Abel Orquera and Ernesto Luis Piana, La vida material y social de los yámana (The Material and Social Life of the Yamana) (Ushuaia, Argentina: Ediciones Monte Olivia, 2015)

Danae Fiore, Body Painting in Tierra del Fuego: The Power of Images in the Uttermost Part of the World, Vol. I, Ph.D. thesis for University of London (London: University College London Institute of Archaeology, 2001)

Museo Territorial Yagan Usi, Ethnographic Collection, Puerto Williams, Chile, visited April 2019

Patricia Stambuk, Rosa Yagán: Lakutaia le kipa (Santiago de Chile: Pehuén, 2011)

Since the Yahgan’s tradition was for someone to paint their face to honor the person they intended to visit, I can’t help but wonder if the Yahgan thought the missionaries were unpardonably rude when they showed up for a visit, or returned a visit, with unpainted faces. Thinking about this makes me want to add that nuance to a scene in my novel, in which a Yahgan character encounters the missionaries for the first time.