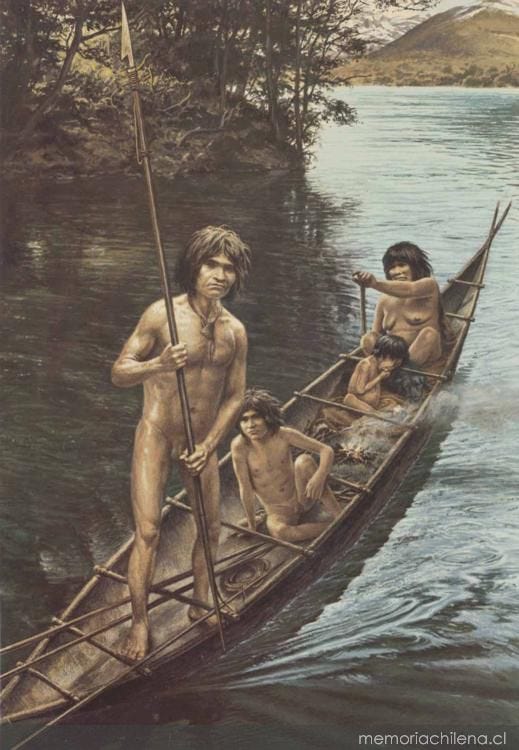

From the earliest encounters between Europeans and the indigenous Yahgan (also known as Yamana), the ingenious bark canoes of Tierra del Fuego captivated the foreigners.

In 1578, Francis Fletcher (part of the crew of Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe) described the Yahgan canoe as fitting “for the pleasure of some great and noble personage, yea, of some prince.”

In 1624, a Dutch expedition exploring Tierra del Fuego described them this way:

Their canoes are truly remarkable. They strip one of the largest trees of all its bark and bend it skillfully, sewing the strips in certain places, giving it the shape of a Venetian gondola. […] These canoes measure 10, 12, 14, 16 feet long and approximately two feet wide. Seven or eight men can sit comfortably in them and they can navigate as fast as a launch with oars.

This post is a celebration of the Yahgan canoe as the highest form of their craftsmanship and technology—proof of how well they, as a people group, adapted to a region Europeans considered wholly inhospitable.

Canoes (called ánan) were the most valuable possession of the Yahgan because each family unit’s survival depended on them for hunting seals, fishing, and moving from place to place. Made from bark (rather than a dug-out trunk), the canoes were light and lasted only a few months on average—but they were remarkably efficient at moving through seaweed patches and storms that hampered heavier vessels, like those of European construction.

In the terms of anthropologist Anne Chapman, Yahgan canoes

were probably “nonperfectible,” the very best […] which could be made with the materials available. The Fuegian canoes were nearly perfect, although, like the sophisticated machinery today, not infallible. Any invention may ultimately exhaust its possibilities for improvement and become nonperfectible though not perfect.

The canoe-makers had achieved this relative state of perfection probably sometime after the Yamana reached the area (6,000 years ago), when countless minds struggled to solve the problems involved with their need for such a vehicle, the materials available, and the changing environment in which they lived.

Most sources say the canoes measured 12 feet to 18 feet (3.75-5.5 meters), depending on the size of the family. They were usually about 2.5-3 feet wide (.7 to .9 meters) and about 3 feet deep (.9 meters).

Women were the ones who mainly rowed, leaving men free to hunt seals and sea lions. Since polygamy was common, usually one wife would paddle from the back while another rowed from the front. Men only rowed if there was a particular need for hurry.

In the middle of the canoe was a low, warm fire on a platform made of stones, clay, sand, and/or grass. Europeans were always surprised to see smoke coming from a canoe, but the fire warmed the paddlers and also meant there was a ready-made way to cook the evening’s dinner, even if the family landed in a place that only offered wet wood. The fire (called pušáki) was always lit. It was the children’s job to tend to the fire and make sure it didn’t go out.

When arriving at the day’s resting place, the women would usually drop off the men and children on shore, with the fire and supplies (including spare firewood). Then the women would tie up the canoe in banks of seaweed, which usually lined the coast, and swim to shore. (Because of this, only women usually knew how to swim.) The canoes were too fragile to drag over the ground or to keep them where they might knock against rocks, so if they needed to keep the canoe safe during a storm or particularly high tide, several adults together might lift a canoe and carry it to a shaded, padded place on shore where it wouldn’t dry out.

Even with careful protection and repairs, canoes usually lasted three to six months.

Bark for new canoes was harvested in the spring (mid-September to November), when sap rises and the bark is easier to loosen from the trunk. The Yahgan used Magellan’s beech (Nothofagus betuloides, known in Spanish as guindo or coigüe blanco), which is a tall, straight evergreen and one of the more common trees in the region.1 Small groups of Yahgan men would make a pilgrimage to a place traditionally known for having the best trees. There, they would look for the tallest, straightest ones, with no low branches.

Because the Yahgan’s lifestyle depended on the water, this was one of the only reasons they might venture very far inland. Sometimes they walked five to eight miles into the forest to find the right tree.

Once they identified a tree with a large section of usable bark, one man would climb and hang suspended from seal-leather straps in order to work from the top down. Using sharp tools made of animal bones, shells, or rock, the men would cut the bark and then peel it away from the trunk with chisels and wedges made of wood or bone. The loose bark would be cradled by seal-leather straps so that it didn’t fall and split. The goal was to get as large of a section of bark as possible, ideally around 16 feet long (5 meters).

When a team of researchers in the 1980s attempted to make a Yahgan canoe using original materials and traditional methods, they found this step incredibly difficult. First of all, they had a hard time deciphering the descriptions of the process recorded by European observers, and then they had a hard time figuring out how, exactly, the tools were used. They had little success: the bark kept splitting.

In the end, the researchers had to content themselves with making a much smaller canoe than originally intended, which fit only one person at a time, because they simply couldn’t keep a larger strip of bark intact.2

Here’s a video of the team’s process, describing some of the difficulties they encountered:

When the Yahgan harvested bark, they gathered at least enough to make two canoes per family. They made one canoe right away and stored the extra bark, for repairs and for another canoe if the first one became unusable before the following spring, underwater to keep it from drying out and becoming brittle.

The construction of a canoe could take 2-3 weeks. The bark was scraped with shell knives and then exposed to fire, which made it as flexible as leather. Several strips were sewn together using bird-bone needles and thread of whale baleen, seal leather, guanaco tendons, or plant fibers.

The canoes were caulked with seaweed or a mixture of clay and animal grease—but they still usually leaked a good bit. This kept the canoes damp, further protecting the boat from the fire it carried.

When Europeans arrived in the region, they introduced metal nails and wood-working tools. Soon, the Yahgan began to opt for heavier boats, made from wooden planks, because they weren’t as fragile. (Even though they also weren’t as fast or as easy to steer as canoes.)

Within a few generations, the traditional canoe-building methods of the Yahgan, which had been in use for around 6000 years, were lost to history. Now only a few full-size examples remain, in museums or private collections around the world. Most are far removed from the context in which they were built, but they still provoke wonder for the skill with which they were made.

This type of tree appears even on Horn Island, where the current southernmost tree in the world is found.

The process of recreating a Yahgan canoe was described by Carlos Pedro Vairo in Los Yamana: Nuestra única tradición marítima autóctona (published in [hard-to-understand] English as The Yamana Canoe: The Marine Tradition of the Aborigines of Tierra Del Fuego). The canoe built by the team of researchers is now on display in the Museo Marítimo (Maritime Museum) of Ushuaia, where Carlos Pedro Vairo is the director.

Man, they took ‘Row, row, row your boat’ to a whole new level!!