The War between Chile and Argentina that ~Almost~ Happened in the 1970s

Why there are still rusty machine guns pointing across the Beagle Channel

I suspect most North Americans would be surprised to hear that countries in South America don’t really get along. But it’s true: Even though the countries have a lot in common and share a good bit of history as former colonies of Spain, there are a lot of old grudges and prejudices that separate Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia (just to name some of the tensions I’m more familiar with).

One time I thought a Bolivian taxi driver might kick my mom and me out of his cab because we lived in Chile at the time, and Bolivia still holds a grudge against Chile for taking away land in a war in 1879-1884. My friend Isabel recently told me that her husband (who’s in the Canadian navy) wasn’t allowed to tell anyone in Chile’s navy that he’d previously participated in a similar navy training event in Peru, because the navies of Chile and Peru DON’T get along (at least in part due to that same war of 1879-1884).

Peru and Ecuador went to war three times in the 20th century, most recently in 1995. And there are still rusted machine guns pointing across the Beagle Channel because of a war that very nearly happened between Chile and Argentina in 1978.

When I say “very nearly happened,” I mean the plans were finalized, the marching orders were given, the ships were deployed, and the helicopters were poised for take-off…but inclement weather delayed the start long enough for the pope to intervene.

To understand the 1978 conflict, we really need to go back to the days of Spanish colonial rule. From the first arrival of Europeans in Tierra del Fuego, the land was claimed for the Spanish crown. Though there was some early English and Dutch activity in the area, rival claims were short-lived. It was pretty understood on an international level: Portugal claimed what we know as Brazil, and the rest of South America, as well as Central America, was the property of Spain.1

During its three-and-a-half centuries of rule, Spain organized its American colonies in different ways at different times, but there were four main centers of colonial government in what are now Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and Argentina. When independence movements began in earnest in the 1810s (after the Napoleonic invasion of Spain), each of the former centers of power declared themselves new, separate entities. Other places that didn’t have close ties to the former seats of power, like Chile, also declared independence on their own.2

The new, independent countries then clashed internally and externally for decades as they struggled to redefine themselves. The South American countries that we recognize today mostly took shape between 1810 and 1830, but civil and international wars continued for the rest of the century.

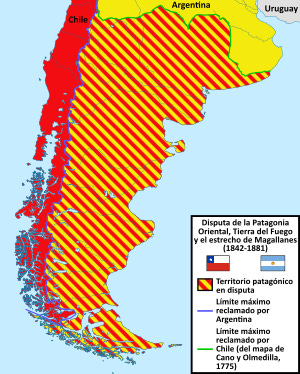

The southern part of South America, including Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, was contested between Chile and Argentina during most of the 1800s. Both countries agreed to go by divisory lines drawn by Spanish colonial administrators, but the problem was that there were different maps from different periods.

That wasn’t too big of a deal, though: that land was considered uninhabitable because the indigenous people who lived there didn’t exactly welcome outsiders. Both countries had more pressing matters to figure out in the north.

It was during this time period that the first white settlers of Tierra del Fuego established their mission in the mostly ignored islands in the far south.

In 1881, when Chile was in the middle of a war with its two neighbors to the north (that war for which Peru and Bolivia still hold grudges), Chile and Argentina signed a treaty to settle the Patagonia issue and to agree on their borders.

Using a Spanish colonial rule that gave Chile access to the Pacific and Argentina access to the Atlantic (with neither having access to both oceans), the two countries peacefully agreed on what would become one of the longest land borders in the world—currently considered the third longest, after US-Canada and Kazakhstan–Russia.

According to the 1881 treaty, the border between Chile and Argentina ran through the Andes, from highest point to highest point (or watershed to watershed)…until just north of the Strait of Magellan. Though Chile was given control of the land north and south of the Strait of Magellan, Argentina got the eastern opening of the strait, and the waterway was officially neutral between the two countries.

Then the border takes a sharp turn to the south, to run vertically until it reaches the Beagle Channel. This splits the main island of Tierra del Fuego into two, with Chile in possession of the western side of the island and Argentina in possession of the eastern side (including the land on which the Anglican mission in Ushuaia was located). The islands south of the Beagle Channel belonged to Chile.

Unfortunately, the “Beagle Channel” itself wasn’t defined in this treaty, which led to a few spats in the 20th century3 and eventually the brink of war in 1978.

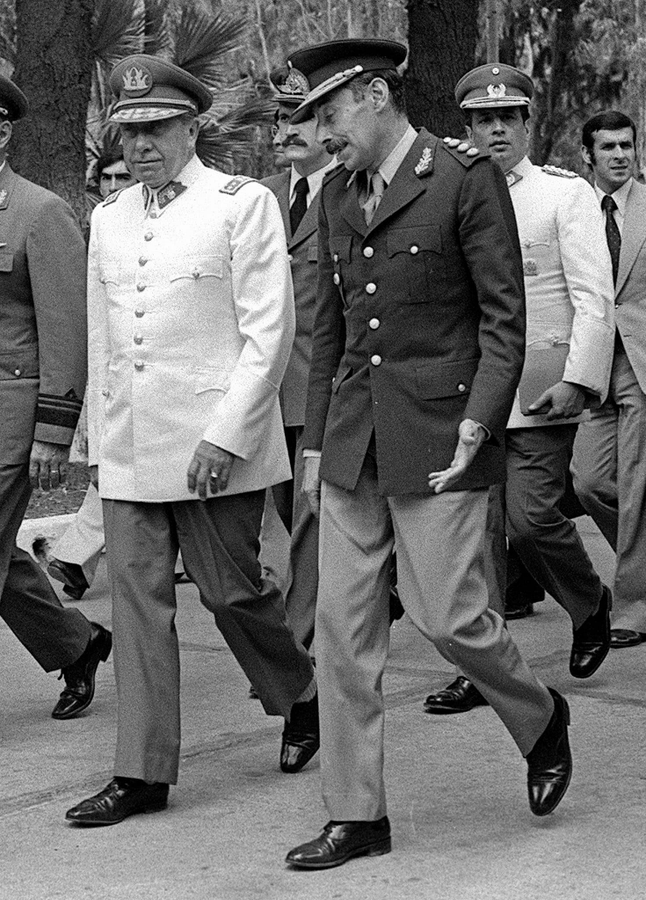

In 1978, both Chile and Argentina were run by military dictators who had obtained power through violence and who were trying to hold on to that power through violent squashing of their opposition. A lot of Chileans and Argentinians “disappeared” and/or were killed by their own government. Protecting the national image was of paramount importance for both leaders.4

So neither side wanted to back down over the contest of three islands at the eastern opening of the Beagle Channel. Picton, Nueva, and Lennox islands were once the territory of the indigenous Yahgan, and they had been a focal point of the gold rush in the late 1880s and early 1890s, but they’d been uninhabited since then. You’d think they would be uninteresting, but fishing rights and navigation routes were at stake—and there was a possibility of oil fields in the area.

Per the treaty of 1881, any territorial disputes between the two countries would be arbitrated by Great Britain, and so Chile and Argentina submitted their differing claims to Queen Elizabeth II. In May 1977, the arbitration ruled in favor of Chile’s claim to all three islands. Argentina rejected the ruling on January 25, 1978, and, despite ongoing negotiations, both countries prepared for war.

Over the course of the year, Argentina closed its border with Chile and kicked out 4000 Chileans.5 There were blackout drills in preparation for bombings—even in Buenos Aires. Troops were recruited and sent south or to the border. Argentina conspired with Peru and Bolivia for those countries to get back the land that Chile took in 1879-1884. Plans were drawn up for a two-pronged plan: first Argentina’s navy would attack Chilean islands in Tierra del Fuego, and then Argentina’s army would cross the Andes at various points to split up Chile and invade the Chilean capital.

Argentina, with a significantly larger population than Chile and a much stronger military, assumed victory would be easy. But if they made the first move, they’d be labelled as the aggressor on the international stage, and the government was already getting unwanted attention because of human rights complaints.

Argentina’s president didn’t want war, but his cabinet was hawkish and pressured him to attack to not appear weak.

Then, on December 21, 1978, the Argentinian order came: the navy was to deploy and invade the Chilean islands. They were hoping to get the fighting over with before Christmas.

But the attack never happened.

A terrible storm blew in on the night of Dec. 21. A summer snowstorm gripped the Beagle Channel, and strong winds kept the helicopters from flying or the ships from attempting a landing.

Argentinians declared God was on the side of the Chileans that night.

The Chileans, meanwhile, weren’t going to take the first step, but they were ready to fight to the final breath for their national sovereignty as soon as the Argentinians crossed the border.

Throughout the night, both militaries were on high alert. The entire hospital staff in Ushuaia slept on campus, ready to attend to casualties as soon as the fighting started.

But the storm went on and on—and then came the order to stand down. Pope John Paul II offered to arbitrate between the two Catholic countries, and Argentina’s president accepted the pope’s offer.

War was avoided.

It did take a while for tensions to fully calm down. Argentina’s president later rejected the cardinal’s decision because it favored Chile. During the Falklands War in 1982, Chile was the only country in Latin America that declared its support for the UK rather than Argentina.

It wasn’t until after the Falklands disaster, in 1982, that Argentina was ready to sign the treaty proposed by the pope, which gave Chile control of the three islands.

Though the two countries are no longer on the brink of war today, and the cannons that were set up on both sides are now oddities covered in graffiti, there is still sometimes prickliness between them.

Tourists are pretty much the only people who cross the Beagle Channel (which was part of how I got stranded on an island in Chile for a week when I visited—stay tuned for that story). Chileans in the town of Puerto Williams are in much closer contact with the city of Punta Arenas, 32 hours away by boat, than they are with Ushuaia, which is a forty minute drive and a half-hour boat ride away.

In 2010, Ushuaia dedicated a plaza in honor of “Las damas centinelas,” the 300 or so women who stayed in the city of Ushuaia when this war was imminent. It wasn’t until 2019 that Chile deactivated the last of the mines its army had left behind on the Beagle Channel islands during the 1978 conflict.

Even though this almost-war may seem petty and distant to outsiders, and though they are close neighbors who share a lot in common, both of these countries have proven their ability to hold grudges for a long time.

Sources:

Juan de Onis, “Chile, Argentina Feud Masks Other Troubles,” The New York Times, published 31 December 1978. Accessed 14 March 2024 through https://www.nytimes.com/1978/12/31/archives/argentina-chile-feud-masks-other-troubles.html.

Nicolás García, “La Armada de Chile finaliza el desminado de las islas del Canal Beagle,” InfoDefensa.com, published 28 November 2019, https://www.infodefensa.com/texto-diario/mostrar/3127754/armada-chile-finaliza-desminado-islas-canal-beagle. Accessed 14 March 2024.

Javier M. González, “Diciembre de 1978, una Navidad al borde de la guerra entre Chile y Argentina,” NuevaTribuna.es, published 21 December 2023, https://www.nuevatribuna.es/articulo/global/historia-diciembre-1978-borde-guerra-chile-argentina/20231221091036221089.html. Accessed 14 March 2024.

Francisco Sánchez Urra, Los soldados del mar en acción (1958-1978): La infantería de marina y la defensa de la soberanía austral (Chile, 2020). Accessed through https://www.armada.cl/custom/radio_naval/libros/soldados_del_mar.pdf

Yes, I’m oversimplifying. Suriname was a Dutch colony. Guyana and Belize were British colonies. French Guiana is still French territory. And the Caribbean islands were way more contested between the different European powers.

There was a brief period of continental cooperation during the wars of independence, and elementary school history lessons in various countries across the continent share the same names of liberators, like José de San Martín, Bernardo O’Higgins, and Simón Bolivar. The independence movements understood that they were doomed to fail in the long run if they couldn’t throw off Spain’s hold on the entire continent. Once Spain was defeated, however, there were too many geographical and cultural divisions—across too vast a continent—for the cooperation to continue. Still, the dream of a united Latin America reappears from time to time—it was an idea that Che Guevara cherished, as you can see in the movie The Motorcycle Diaries, for example.

The worst of these spats was the Snipe Incident in 1958. Chile built a lighthouse on the uninhabited Snape Island (really, an islet: it’s about half a mile long and not even a thousand feet wide) purportedly for the purpose of improving navigation through the channel. The Argentine navy destroyed the lighthouse because they said that wasn’t Chilean land. They ordered a new, Argentinian lighthouse in its place. The Chilean navy dismantled the Argentinian lighthouse and took away the pieces, then installed a new Chilean lighthouse. The Argentinians destroyed that and deployed a military squadron to protect the island. Then both countries signed a treaty to back down and keep the previous status quo—no lighthouse and no military presence.

This led to what may be the most infamous soccer tournament ever: the 1978 World Cup, hosted by Argentina. It was a major propaganda tool for the military government, which tried to show that everything was okay within the country (despite many allegations of human rights abuses). Argentina won the tournament…which may or may not have been because other teams felt threatened by host president when he visited their locker rooms, the refs were afraid of making calls against Argentina, and the Argentina squad feared for their lives if they lost.

This really affected estancias in Argentinian Tierra del Fuego because Chileans made up a significant proportion of the farm laboring jobs. That’s still the case today. What I was told when I visited was that Argentinians tend to think that sort of menial labor is beneath them.