“Tierra del Fuego” translates to “Land of Fire” in English (or, as the first English-speaking settlers called it, “Fireland”). But the first Europeans to explore this part of the world—Ferdinand Magellan’s crew—actually called it “Land of Smoke,” because of the columns of smoke they saw rising above the forests to the south. They assumed this meant that land was inhabited, but they didn’t see or interact with the people themselves.

At the time, maybe 10,000 people1 lived in the region south of what’s now known as the Strait of Magellan. They lived in four distinct people groups: the Selk'nam (Ona), Yámana/Yahgan, Kawésqar (Alakaluf), and Manek'enk (Haush) indigenous cultures.2 The Yahgan had been there for about 6,000 years3, navigating the interior channels of the archipelago, fishing and hunting from their canoes.

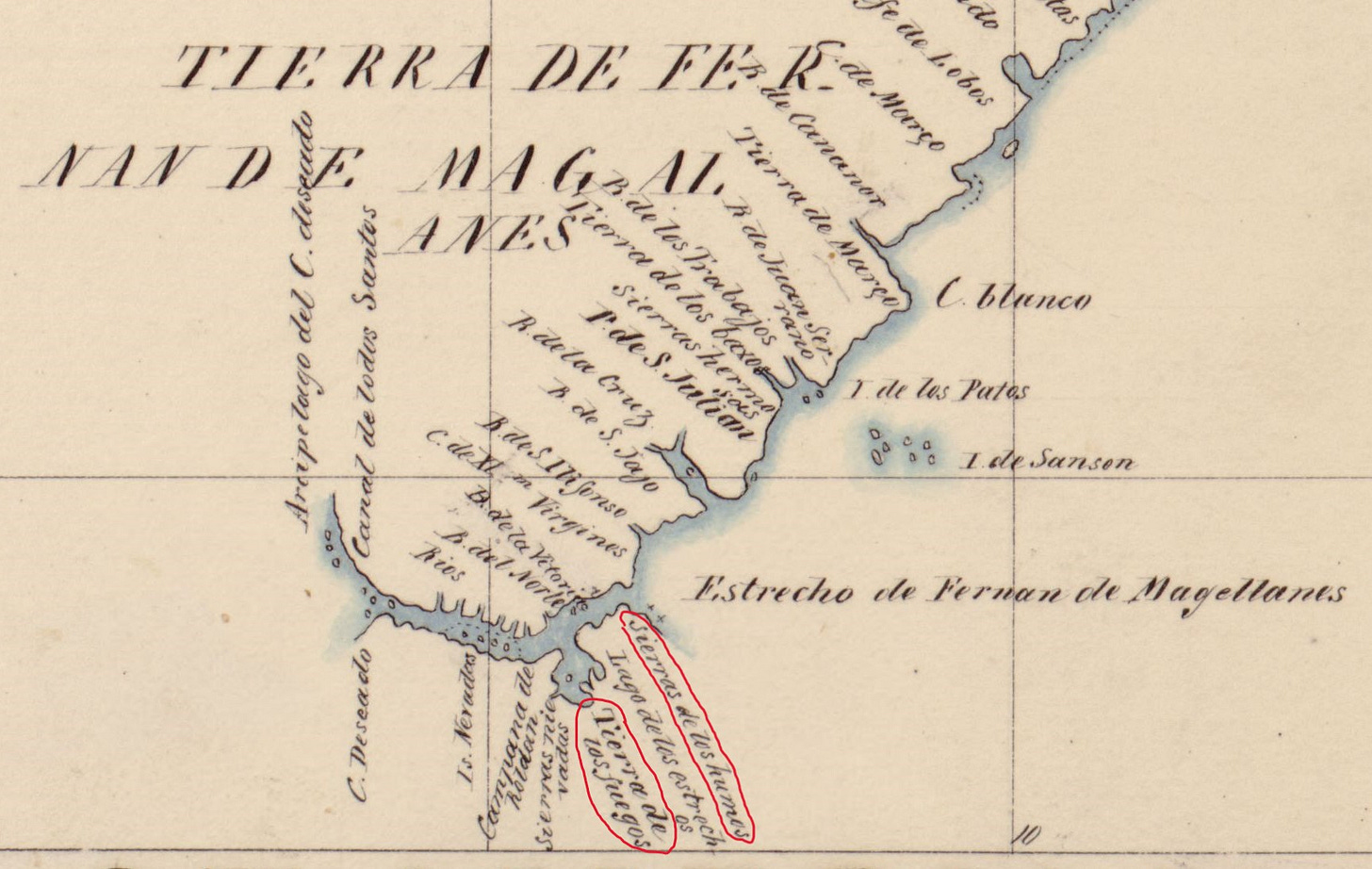

When Ferdinand Magellan made it back to Spain after his 1520 expedition, the Spanish king Carlos V supposedly said, “Where there is smoke, there are fires in the land,” and mapmakers began labelling the unexplored land south of the Strait of Magellan as “Tierra de los Fuegos” (eventually simplified to “Tierra del Fuego”).4

I’ve also heard it said that the mapmakers thought “Land of Smoke” didn’t sound very appealing and wouldn’t make people want to buy their maps to travel there. If so, the name “Land of Fire” could be considered a marketing decision from the 1500s…but that’s probably just conjecture.

Regarding the fires that caught the Europeans’ attention, a later indigenous resident of Tierra del Fuego explained them as “signals lit by the Ona. The arrival of something as strange as the first ship would certainly be worth calling the attention of the other Indians.”5 The guidebook where I found this goes on to say:

The early expeditions also observed columns of smoke moving over the channels to the west. The Yahgan and Alacaluf built fires in their canoes, and on clear days it would be possible to see tall columns of smoke without seeing the low canoe itself.

The early missionaries did not fear the Indians so much as their fires. Among the Yahgans it was customary to burn large areas of land as a diversion, to find birds’ eggs, or as part of the young men’s initiation ceremonies, during which they had to light various fires on nearby heights. The missionaries had such a fear of these getting out of hand that they sent for an uninflammable “Iron House” from England. The Ona also burnt lands for similar reasons, including the death of a tribal member.

Fire was indispensable to the Indians; they always carried fire or the elements to make fire with them wherever they went. The modern Fuegian also lives near his fire, always the most popular gathering spot in any home. And flares—from the oil fields—are still seen from the Strait of Magellan.6

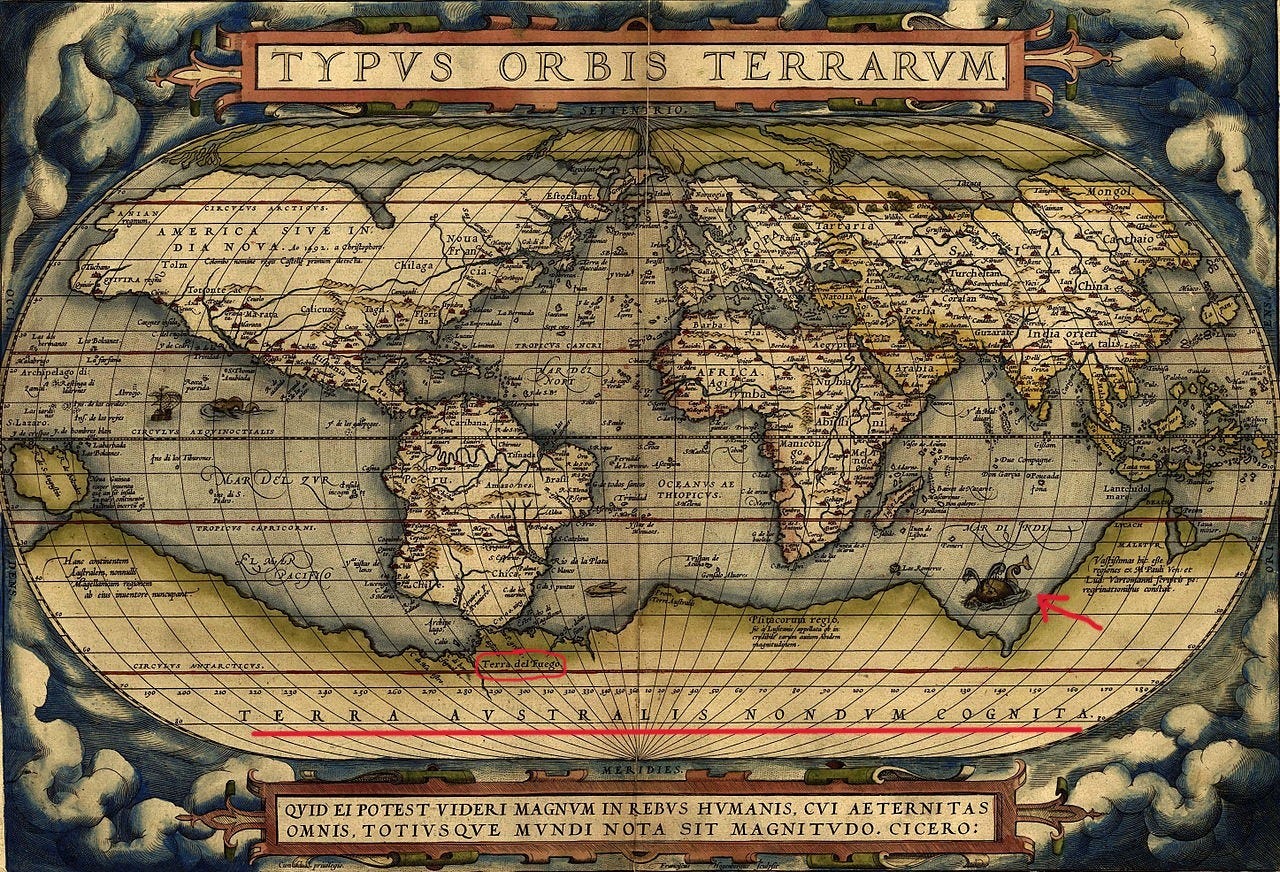

For more than fifty years after Magellan, Europeans assumed this area was part of a wondrous southern continent, known as “Terra Australis Incognita” (or “The Unknown South Land”) thanks to Ptolemy (90-168 AD).

Naturally, monsters lived there.

Englishman Francis Drake, in 1578, was the first to understand Tierra del Fuego wasn’t part of Terra Australis. The members of Drake’s expedition were also the first Europeans to interact with the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, but they didn’t realize at the time what a remarkable event that was.

Maps then moved Terra Australis a little south of Tierra del Fuego, which was correctly represented as a group of islands. Note that the vast continent of Terra Australis was still only conjecture—nobody had seen it, but Europeans thought it was necessary to balance out the landmasses on the northern part of the globe. “Symmetry demanded it, the balance of the earth demanded it—for in the absence of this tremendous mass of land, what […] was there to prevent the world from toppling over to destruction amidst the stars?”7

It wasn’t until James Cook’s 1774 expedition that the existence of Terra Australis was disproved8, and this ushered in a new age of exploration of the southern oceans—and exploitation by whalers.

For three hundred years after Magellan’s expedition put “Tierra de los fuegos” on the map, the native inhabitants of this region were largely undisturbed, only occasionally visited by European or American seal-hunters, whalers, or explorers (which encounters were sometimes violent). Those who wrote records of their voyages frequently described the area as “dreary” and “inhospitable” and labelled places with names like “Desolation Cape,” “Desolate Bay,” and “Desolation Island.”9

But for the native inhabitants, this region of snow-covered mountains, forests, ocean currents, and strong winds was simply home, and there were hundreds of native names for the multitude of channels, bays, and islands that make up the archipelago we know today as Tierra del Fuego.

This is Thomas Bridges’ estimate of what the population was in the mid-1800s, which is the earliest number I’ve seen. By using this number as a ballpark for an earlier era, I’m assuming the population was generally stable during the 300 years when there was limited contact with the Europeans. That’s probably not a good scholarly assumption…which just confirms I’m a fiction writer, not a historian. :-)

In this post, I share a map that shows the distribution of the people groups throughout South America. That map might also be helpful as an orientation, showing the location of Tierra del Fuego on a recognizable (current) map of South America.

This number comes from Anne Chapman’s European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 15. I rely on that book a lot in my different posts.

This version of the origin of the name “Tierra del Fuego” (and references to the maps shown) comes from an article (in Spanish) published on the Argentinian news site El Diario del Fin del Mundo, out of Ushuaia.

This comes from Rae Natalie Prosser Goodall’s guidebook Tierra del Fuego, citing the opinion of Luis Garibaldi Honte (Ediciones Shanamaiim, 1979).

Goodall, Tierra del Fuego, p. 14

John C. Beaglehole’s The Exploration of the Pacific, Stanford University Press, 1968, p. 9, as quoted in Anne Chapman’s European Encounters, p. 39.

Cook conjectured at the existence of a land of ice further south, and the actual continent of Antarctica was sighted in 1820, but this was very different from the lore of Terra Australis, which was thought to be a “golden and spicy province, the land of dye-woods and parrots and castles” (John C. Beaglehole, The Life of Captain James Cook [Stanford University Press, 1979], p. 107, as quoted in Anne Chapman’s European Encounters, p. 50).

Anne Chapman, European Encounters, p. 40-41.