Charles Darwin and the Yahgan—What He Got Wrong and How He Changed His Mind

Why the famous scientist gave the Yahgan the reputation of "miserable, degraded savages" and cannibals

In 1831, a 22-year-old recent Cambridge graduate was invited to be a naturalist on board a British survey ship tasked with completing a hydrographic chart of South American waters and taking other measurements on a circumnavigation of the globe. Charles Darwin published his experiences in The Voyage of the Beagle (1845) and returned to his observations repeatedly in his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859) and other works that lay out his theory of “descent with modification” (evolution).

In these books, which were much read and discussed in Europe and the US over the next several decades, Darwin unfortunately described the Yahgan of Tierra del Fuego as “savages of the lowest type imaginable” and “the lowest barbarians”—so much so that “one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures and inhabitants of the same world”—and he popularized his misunderstanding of them as cannibals.

It would take decades for missionary Thomas Bridges (and others) to set the record straight about the world’s southernmost people group.

Charles Darwin had planned to pursue theological studies and become an Anglican priest, but he abandoned those plans (as he had several other career paths previously) when one of his former professors recommended him for the job of on-board naturalist, “not on the supposition of [his] being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, and noting any thing worthy to be noted in Natural History.”

Darwin almost wasn’t hired, because Captain FitzRoy “took a dislike to him, particularly his nose; it was not the nose of a man who could endure the rigors of a voyage around the world.” FitzRoy was won over, however, and Darwin joined the expedition, with his father paying his personal expenses for the 5-year journey.

In addition to its official task of completing the survey of South American waters (begun on a previous expedition from 1826-1830), the Beagle’s return trip to Tierra del Fuego had another, personal purpose for Captain FitzRoy: fulfill his promise to repatriate three young indigenous people he’d taken to England in 1830.1

During the first year of sailing, as the Beagle made a number of stops on the way to Tierra del Fuego, Darwin came to know the three indigenous passengers on board, particularly the Yahgan teenager known as Jemmy Button, who was “merry” and sociable, “a universal favorite” among the crew, who “often laughed and was remarkably sympathetic with anyone in pain.” Darwin wrote, “In contradiction of what has often been stated, 3 years has been sufficient to change savages, into, as far as habits go, complete and voluntary Europeans.” In particular, Jemmy Button “used to wear gloves, his hair was neatly cut, and he was distressed if his well-polished shoes were dirtied. He was fond of admiring himself in a looking-glass.” Darwin definitely considered them worthy to be treated as fellow humans, because he wrote, “The three natives on board H.M.S. Beagle who had lived some years in England, and could talk a little English, resembled us in disposition and in most of our mental faculties.”

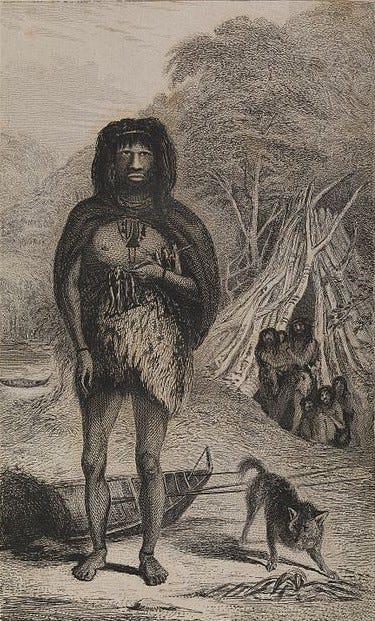

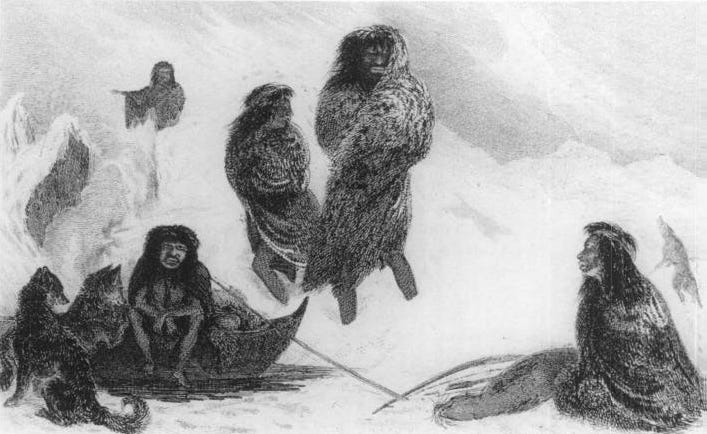

Despite his good opinion of the indigenous Fuegians he knew personally, when Darwin met the Yahgan in their own environment, his description makes them sound more like animals than humans:

These were the most abject and miserable creatures I anywhere beheld. [… They] were quite naked, and even one full-grown woman was absolutely so. It was raining heavily, and the fresh water, together with the spray, trickled down her body. In another harbor not far distant a woman who was suckling a recently born child came one day alongside the vessel, and remained there out of mere curiosity, whilst the sleet fell and thawed on her naked bosom and on the skin of her naked baby! These poor wretches were stunted in their growth, their hideous faces bedaubed with white pain, their skins filthy and greasy, their hair entangled, their voices discordant and their gestures violent. Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures and inhabitants of the same world. It is a common subject of conjecture what pleasure in life some of the lower animals can enjoy: how much more reasonably the same question may be asked with respect to these barbarians! At night five or six human beings, naked and scarcely protected from the wind and rain of this tempestuous climate sleep on the wet ground coiled up like animals.

In his summary of The Voyage of the Beagle, he wrote:

Could our progenitors have been men like these? —men, whose very signs and expressions are less intelligible to us than those of the domesticated animals; men, who do not possess the instinct of those animals, nor yet appear to boast of human reason, or at least of arts consequent on that reason. I do not believe it is possible to describe or paint the difference between savage and civilized man. It is the difference between a wild and tame animal.

He also wrote, “They are such thieves and so bold cannibals that one naturally prefers separate quarters.”

It’s worth remembering that Darwin wasn’t an ethnographer, and his primary focus was to take note of plants, animals, and geological formations—so he simply seems to have missed spiritual beliefs and arts among the Yahgan, evidenced in the geometric patterns of their face and body paints, their songs, and their stories. He also didn’t recognize what future anthropologists would point out about the many ways the Yahgan adapted well to their environment, both in their bodily ability to withstand cold and in their ingenuity in using whale and seal blubber as an ointment to insulate their bodies against the elements.

And though Darwin was an original thinker in many respects, he was also a product of his day, heavily influenced by the then-popular philosophy of social progress that ranked cultures hierarchically “from the lowest (the Fuegians, aboriginal Australians and the like) to the highest (the civilized Europeans).”

The indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego were also the first people groups a young Charles Darwin encountered in their traditional culture—so I think it’s fair to say some culture shock was probably at play. We can only guess how much of his criticalness and fearfulness toward them can be chalked up to the disorientation he felt from being surrounded by such completely different cultures for the first time.

Another factor that may have influenced Darwin’s poor opinion is the weather. Darwin was frequently seasick even when the sailing wasn’t particularly rough, and a little after they arrived in Tierra del Fuego, the Beagle barely survived one of the worst storms some of the sailors had ever seen.2 After a day of actually nice weather, Darwin wrote in his journal that “if Tierra del Fuego could boast one such day a week, she would not be so thoroughly detested as she is by all who know her.” He summarized his overall experience as notable for surviving “the very worst weather in one of the most notorious places in the world.”3

However, Darwin’s poor opinion of the Yahgan mostly seems grounded in his (mis)understanding of them as cannibals. As Darwin wrote in one letter, “Was ever anything so atrocious heard of, to work [the women] like slaves to procure food in the summer and occasionally in winter [then] to eat them—I feel quite a disgust at the very sound of the voices of these miserable savages.”

Darwin’s description of this (supposed) cannibalism shows his horror was compounded by the cruelty he thought it entailed:

When pressed in winter by hunger, they kill and devour their old women before they kill their dogs: [on] being asked […] why they did this, [one source] answered, “Doggies catch otters, old women no.” The boy described the manner in which they are killed by being held over smoke and thus choked; he imitated their screams as a joke, and described the parts of their bodies which are considered best to eat. Horrid as such a death by the hands of their friends and relatives must be, the fears of the old women, when hunger begins to press, are more painful to think of; we were told that they then often run away into the mountains, but that they are pursued by the men and brought back to the slaughter house at their own firesides!

This, however, was a pretty big mistake. Darwin never looked for evidence of cannibalism among the people; instead, his assumptions relied on the information given by two main sources: Jemmy Button and a boy called Bob, captured by a sailor on a different expedition. As Anne Chapman explains, Darwin should have known better than to draw such a big conclusion from these sources, “Darwin himself noted that Bob […] was ‘called a liar, which in truth he was.’ It is also strange that Darwin cited Jemmy as a reliable source for cannibalism, when a few pages before he stated ‘it was generally impossible to find out, by cross-questioning, whether one had rightly understood anything which [Jemmy Button] had asserted.’ He also remarked that Jemmy would not eat land birds because they ‘eat dead men.’”

In 1888, Thomas Bridges wrote to the English Literary Society of Buenos Aires (later republished in the preface to his dictionary):

These natives, Yahgans, have always been misunderstood and made out worse than they are. They have been called cannibals and the sketches of them have been caricatures rather than the truth. They will eat neither fish nor meat in its raw state. […] Cannibalism is utterly impossible amongst these aborigines by the laws of their society of living, in which human life is considered sacred and every relation of a murdered man considers himself bound to avenge the death. There have been times of extreme famine when on account of the bad weather it has been impossible for them to obtain provisions[…]. At such times I have known them to eat their foot-gear and their raw-hide thongs, without a suggestion that they should eat human flesh.

In Lucas Bridges’ 1948 account of his family’s experiences in Tierra del Fuego, he also felt the need to address Darwin’s accusation of cannibalism:

We who later passed many years of our lives in daily contact with these people can find only one explanation for this shocking mistake. We suppose that, when questioned, […] Jemmy Button would not trouble in the least to answer truthfully, but would merely give the reply that he felt was expected or desired. In the early days [the three indigenous captives’] limited knowledge of English would not allow them to explain at any length, and, as we know, it is much easier to answer ‘yes’ than ‘no.’ So the statements with which [Jemmy Button] has been credited were, in fact, no more than agreement with suggestions made by their questioners.

We can imagine [Jemmy and the other indigenous captives’] reactions when asked what was, to them, a ridiculous question. […] They would at first be puzzled, but when the enquiry was repeated and they grasped its meaning and realized the answer that was expected, they would naturally agree. […]

These irresponsible youngsters, encouraged by having their evidence so readily accepted and noted down as fact, would naturally start inventing on their own. […] This delectable fiction once firmly established, any subsequent attempt at denial would not have been believed, but would have been attributed to a growing unwillingness to confess the horrors in which they had formerly indulged. Accordingly, these young story-tellers allowed their imaginations full rein and vied with each other in the recounting of still more fantastic tales.

Darwin’s misunderstanding of the Yahgan was long-lived and influential. Generations of sailors passing through (or shipwrecked in the area), as well as sealers and whalers working in the region, were terrified of a cannibalistic attack and so sometimes shot at any indigenous Fuegians they sighted. When Allan Gardiner and his missionary teammates set up camp among the Yahgan, their terror of cannibalism likely contributed to their eventual choice to isolate themselves from the Yahgan, even though that ultimately led to their death by starvation.

In 1860, Charles Darwin had some follow-up questions about the Yahgan, and he ended up writing to a young Thomas Bridges, who at eighteen was the interim director for the Anglican mission among the Yahgan, then based in the Falkland Islands. Darwin was curious about Yahgan mannerisms and expressions, and Thomas Bridges’ response stuck pretty closely to the questions presented, giving only the information asked for. (At that point, Thomas Bridges may not have been familiar with Darwin’s misconceptions about the Yahgan, or he may have been too timid to correct a famous scientist.) Darwin credited Bridges with the information when he referenced it in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872).

It wasn’t until the 1870s, after the Anglican mission at Ushuaia was well established under Thomas Bridges, that the global reputation of the Yahgan began to change. In their navigational charts for the region, the British Admiralty began to reassure sailors, “In the event of a crew being wrecked [off Cape Horn], the best course to Ushuaia is east of False Cape Horn, and through Ponsonby Sound, where natives would be ready to pilot any shipwrecked crew to Ushuaia. A great change has been effected in the character of the natives generally, and the natives […] can be trusted.”

In a charitable meeting in February 1884 for the benefit of the South American Mission Society, at which the mayor of London presided, one of the guests of honor, the Earl of Shaftesbury, praised the work of Thomas Bridges and said, “I have read somewhere that the great philosopher, Mr. Charles Darwin, had the candor to admit—and it is a great thing to have candor among such men—that the people of Tierra del Fuego had undergone an improvement which greatly astonished him. He had supposed that they were altogether irreclaimable, and must continue in their degraded condition in which he had found them, but when he heard of the triumph achieved by the missionaries, and of the advance of the natives in the social scale, he confessed that he had made a mistake, and sent a contribution of funds to the Society.”

While that description of Darwin’s changed opinion may be a bit of a dramatic overstatement, Darwin did keep up with news of the Ushuaia mission through correspondence with his friend B.J. Sulivan, who had been an officer on the Beagle and was an involved supporter of the South American Missionary Society. One of Darwin’s letters to Sulivan says, “I have often said that the progress of Japan was the greatest wonder in the world, but I declare that the progress of Fuegia is almost equally wonderful.” Another letter says, “I certainly should have predicted that not all the missionaries in the world could have done what has been done.” Responding to Sulivan’s initiative, Darwin also regularly contributed funds for the support of Jemmy Button’s grandson, known as James FitzRoy Button, who was an orphan at the Ushuaia mission.

So Darwin may not have ever exactly admitted his mistake in calling the Yahgan cannibals or apologized for popularizing his opinion of them as “the lowest barbarians” and “miserable, degraded savages,” but he did admire the (so-called) “civilizing” “progress” effected by the missionaries among them.

In any case, Tierra del Fuego and its people left a strong mark on Charles Darwin. He wrote in his Autobiography, “The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career. […] I have always felt that I owe to the voyage the first real training or education of my mind. Looking backwards I can now perceive how my love for science gradually preponderated over every other taste… the sense of sublimity, which the great deserts of Patagonia and the forest clad mountains of Tierra del Fuego excited in me, has left an indelible impression on my mind. The sight of a naked savage in his native land is an event which can never be forgotten.”

It’s just too bad other people had to set the record straight about those people he called “savages.”

SOURCES

Lucas Bridges, Uttermost Part of the Earth (New York: The Rookery Press, 2007), 33-36

Thomas Bridges, Yamana-English Dictionary of the Speech of Tierra del Fuego, “Preface” (Mödling, Austria: Missionsdrukerei St. Gabriel, 1933)

Anne Chapman, European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010), 97-142

Darwin Correspondence Project, Cambridge University Library, letters no. 2640, 2643, 12399, 13092, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk, accessed 24 May 2024

Janet Browne, “Darwin the Young Adventurer,” Humanities, May/June 2009, https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2009/mayjune/feature/darwin-the-young-adventurer, accessed 24 May 2024

South American Missionary Magazine, vol. XVIII—1884 (London: South American Missionary Society, 1884), 57

These three young people were an Alacaluf (Kawéskar) little girl known as Fuegia Basket (whose native name may or may not have been Yorkicushlu), a 20-something Alacaluf (Kawéskar) young man called Elleparu (known to English speakers as “York Minster,” for the place where he was taken captive), and a teenage Yahgan boy called Orundelico (known as Jemmy Button, who became the most famous of the Yahgan because of FitzRoy and Darwin’s accounts of him and because subsequent English speakers sought him out as a translator whenever they passed through the region). A fourth indigenous passenger, known as Boat Memory, died of smallpox soon after arriving in England.

FitzRoy mostly treated them as guests on board his ship, and he watched over them protectively when they were in England, so that afterwards they spoke positively of their English friends. However, the captain initially captured Fuegia Basket as a hostage he hoped to trade for the return of a whaleboat that was stolen from his crew, and he made no attempts to explain to them or their families his intention to carry them across the ocean, away from their homelands. He later revised his intentions to say he hoped to help the indigenous Fuegians by seeding among them members of their own people who had enjoyed the benefits of English education and Christian teachings. FitzRoy, a devoted Christian, also planned to set up a missionary to live among the Yahgan, but that didn’t work out. FitzRoy may have been a benevolent captor, but I think it’s still be accurate to describe the three indigenous passengers as captives.

This was, apparently, a huge storm that covered a significant area. It sunk at least four other ships.

Darwin did, however, find things to admire about the scenery. About the Beagle Channel (named after their ship, which had “discovered” the waterway on its previous expedition), Darwin wrote: “This channel […] is a most remarkable feature in the geography of this, or indeed of any country.” Later, after he’d been in the region for a while, Darwin described the Northwest Arm of the Beagle Channel with evident awe: “The scenery here becomes even grander than before. the lofty mountains on the north side compose the granite axis, or backbone of the country, and boldly rise to a height of between three and four thousand feet, with one peak above six thousand feet. They are covered by a wide mantle of perpetual snow, and numerous cascades pour their waters, through the woods, into the narrow channel below. In many parts, magnificent glaciers extend from the mountain side to the water’s edge. It is scarcely possible to imagine anything more beautiful than the beryl-blue of these glaciers, and especially as contrasted with the dead white of the upper expanse of snow.”

A fascinating and well researched piece, Christine.

Aah, whom you do not understand you often think ill of.