"A Remarkably Complex Language"

The uniqueness of the Yahgan language and how it was preserved

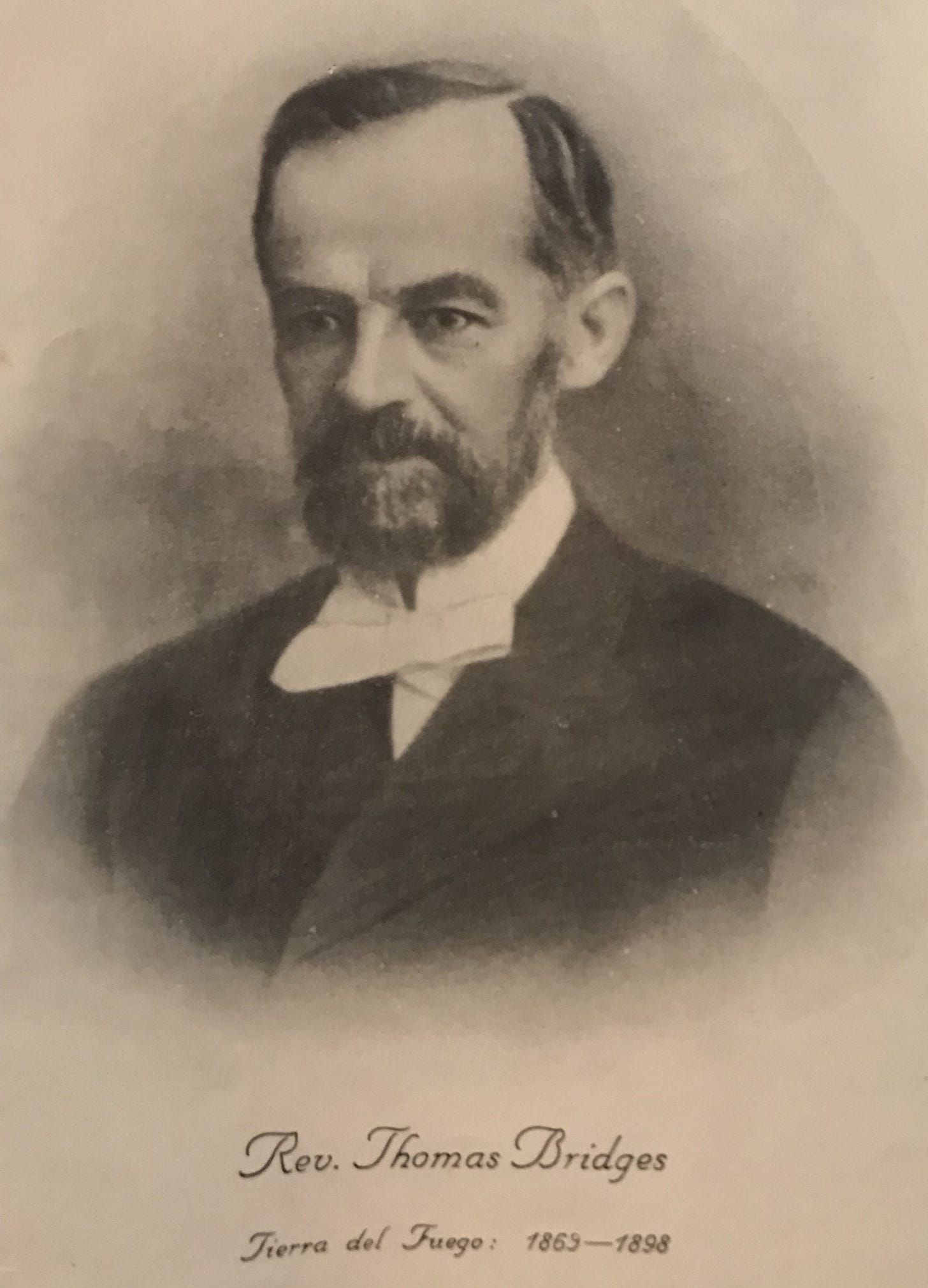

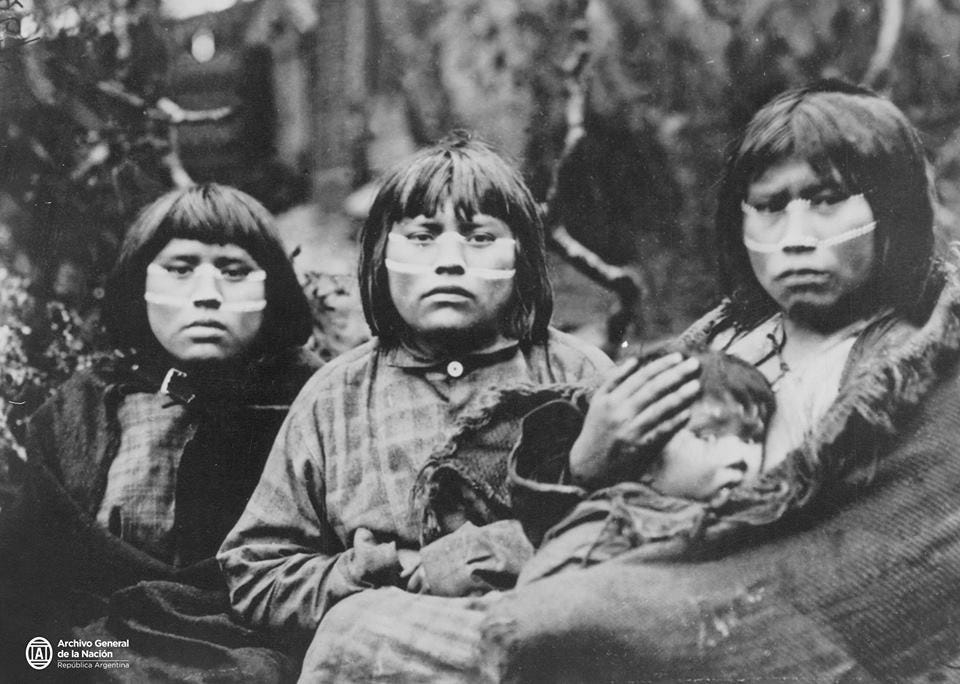

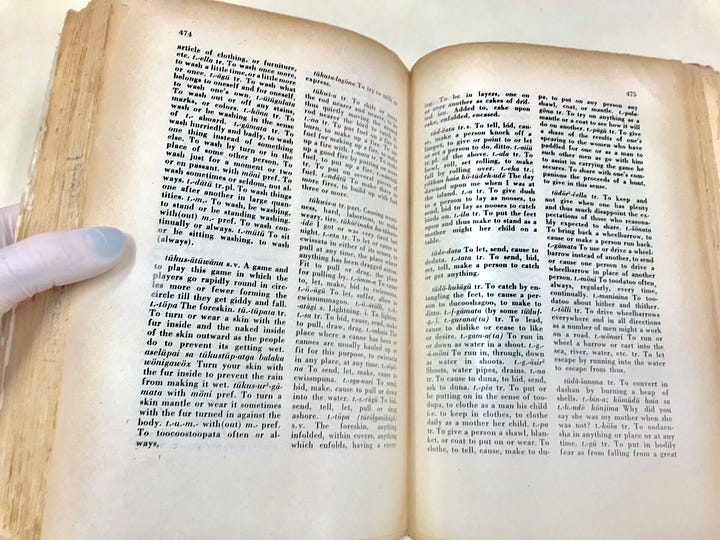

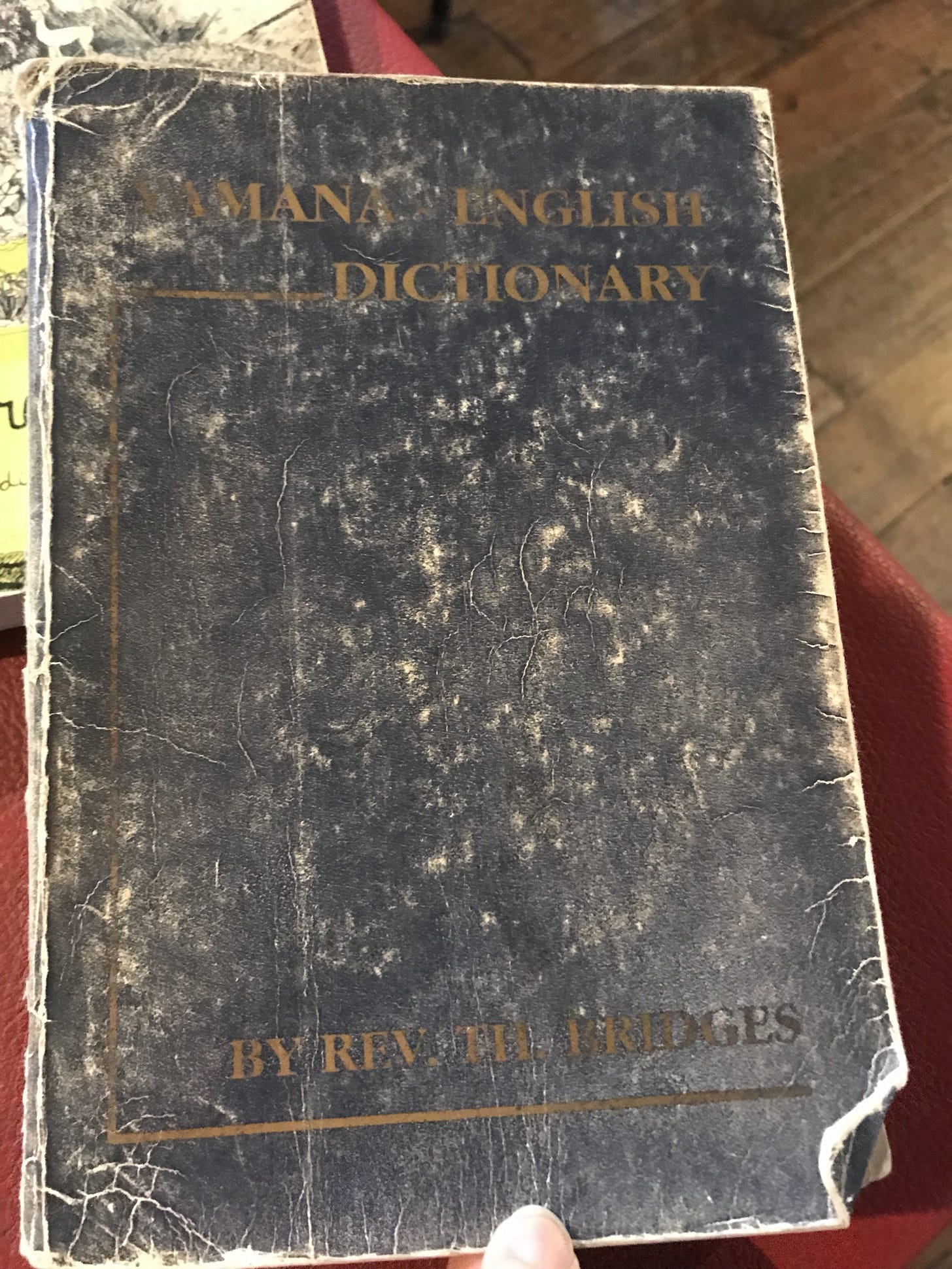

Though Charles Darwin wrote of the indigenous Yahgan of Tierra del Fuego as “the lowest barbarians” on Earth, the missionary Thomas Bridges thought the famous scientist would have changed his mind if he’d understood the complexity of the Yahgan language.1 Bridges himself compiled an English-Yahgan dictionary that cataloged more than 32,000 words, creating one of the most complete records we have of a native American language that has since disappeared from regular use.

Ever since, linguists around the world have puzzled over and marveled at the Yahgan language. The dictionary also has its own story, worthy of an epic, which I couldn’t help but incorporate into my novel.

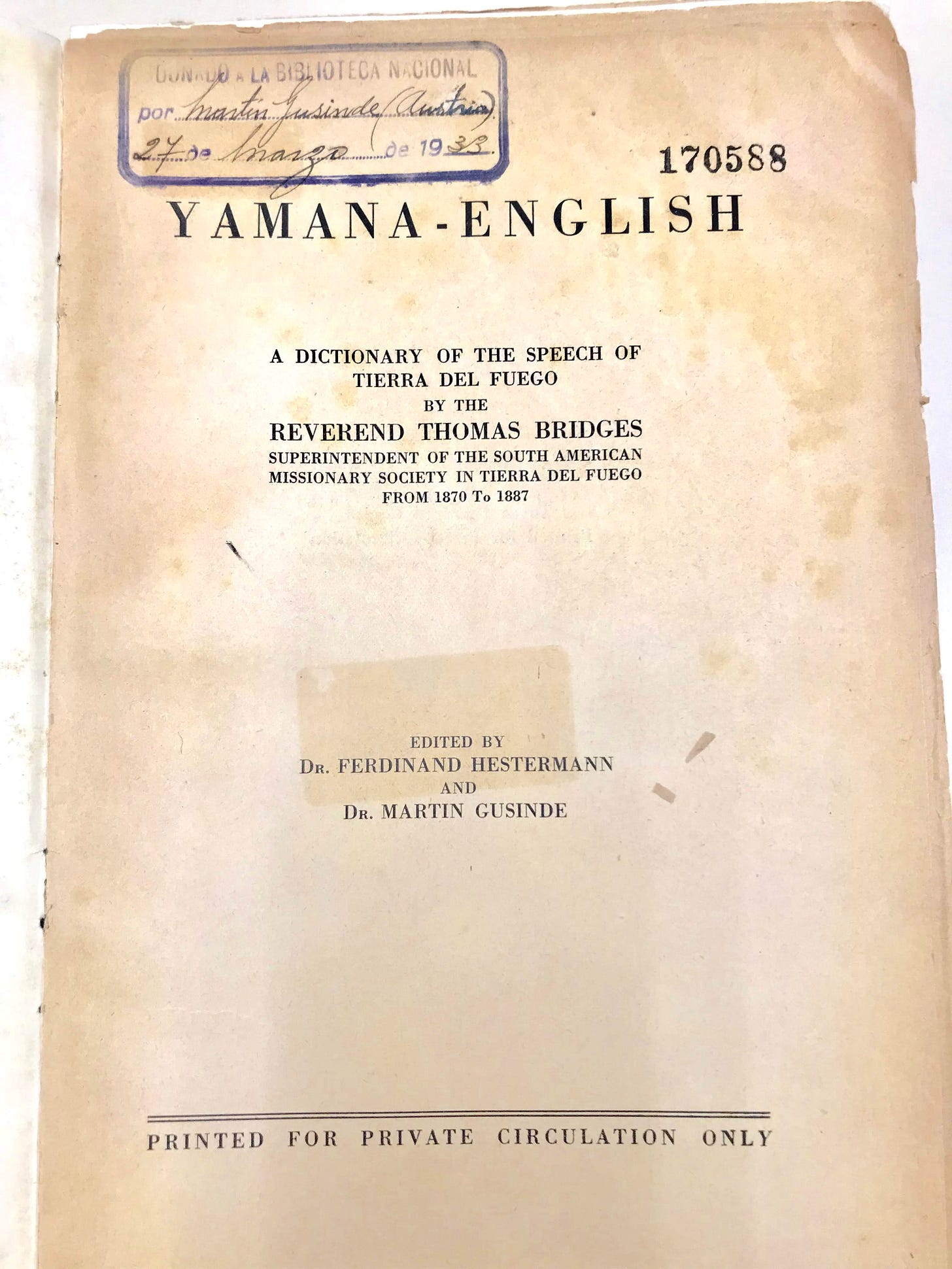

When Thomas Bridges’ dictionary was published in 1933—thirty-five years after the missionary’s death—it was labelled in the preface as “a unique human exhibit and a major achievement in the science of Philology [linguistics].”

To put into context the number of words in the Yahgan dictionary—each of them “distinct […] not overlaid by the speech of other tribes, even of their immediate neighbors”—consider that the first English dictionary included only 3,000 words. The Oxford English Dictionary contains more than 170,000 words, but about 80% of these are derived from another language (mostly Latin and Greek). A fluent English speaker knows an estimated 40,000 words.2

Thomas Bridges wrote, “Incredible though it may appear, the language of one of the poorest tribes of men, without any literature, without poetry, song, history or science3, may yet […] have a list of words and a style of structure surpassing that of other tribes far above them in the arts and comforts of life.”

Based on characteristics of the language, Bridges concluded that Yahgan was a very old language, spoken by the people of Tierra del Fuego for thousands of years, with very limited influence from other languages. It appears to have been completely unrelated to any other known languages, including those of neighboring people groups.

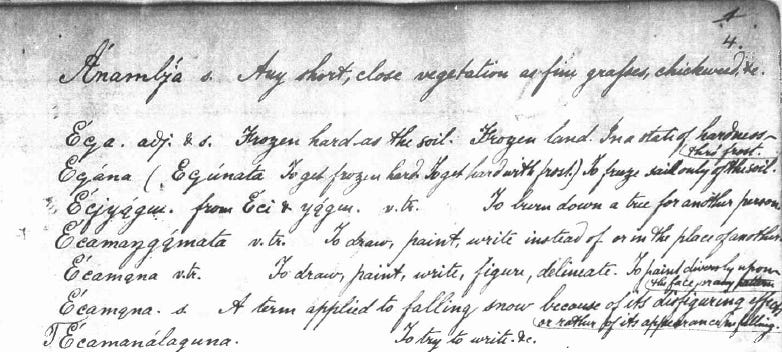

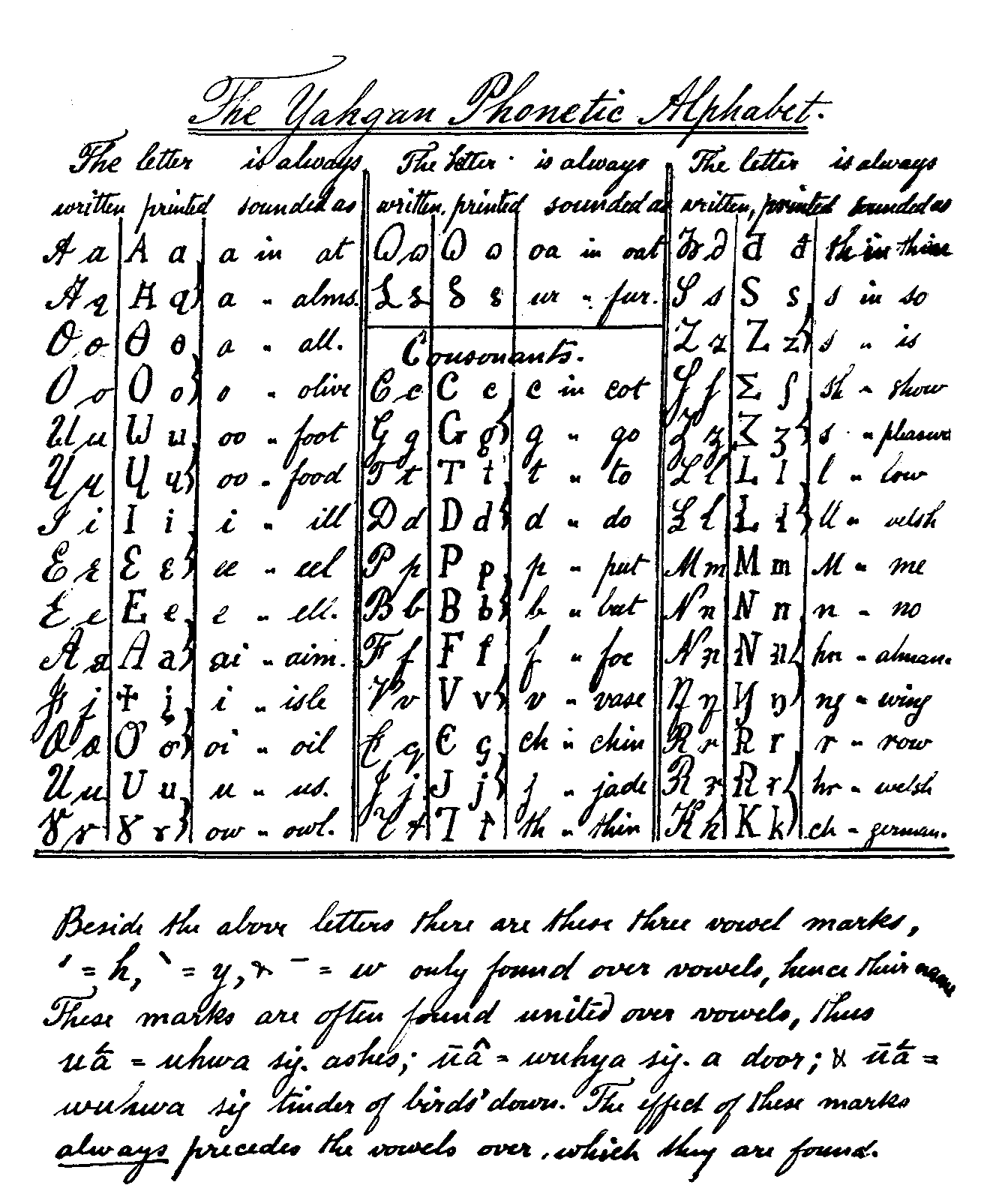

The complexity of the Yahgan language may be appreciated through three particular observations by Bridges:

It has far more terms than has English descriptive of kindred. Thus, whilst the English list comprises 25 terms, the Yahgan has 61. English assists its deficiencies by descriptive terms as younger, elder, uncle on the mother's or father's side, etc., whilst Yahgan has totally distinct words for each term. […]

In pronouns, Yahgan is decidedly ample. Besides the universal pronouns I, thou, he and she, with their inflections for case and number, Yahgan has quite a host of others which indicate the respective places of the persons spoken to, or spoken of, with respect to the wigwam, or to the person speaking or addressed. Thus Anchin, Cunjin, Siuan, Inga, Ura, Ili, Hoagu, Scu, Hoamatu, Simatu, Hoakillu, Singillu, Hoamachi, Simachi, Kichicillu, Scapu, Scagu, Kichicagu, and many others, all mean he or she, but have reference to either distance or nearness, to different points or directions or to position as higher or lower, in or out, etc. […]

But it is in verbs that Yahgan swells out into great bulk. […] [It has] very many [verbs] for which English has no equivalents. Here is a remarkable instance: Hatanisanude, I thought so, when the supposition was correct, but Hayengude, I thought so, when it was false. […] There are many other ways in which the Yahgan verbs amplify themselves in an extraordinary manner, but the above will suffice to show that, owing to these various incidents, it is a language having a great compass of words.

Bridges worked on the dictionary over the course of his forty-two years among the Yahgan. The work was actually begun by Thomas’s missionary adopted father, the Rev. Despard, when Thomas was thirteen years old, but Despard didn’t make much progress on it. When Despard returned to England and left eighteen-year-old Thomas in charge of the mission station, Thomas took over the dictionary. He even lived for a while in the same hut as two Yahgan men (an unusual practice among this group of missionaries) so that he could better learn the language. He continued work on the dictionary, and an accompanying grammar, right up until his death in 1898.

During his lifetime, Bridges translated into Yahgan and published (anonymously) three books of the Bible, plus the Lord’s Prayer, for the aid of his mission work. The dictionary, however, was not published. It existed only in manuscript form, in notebooks written out by hand. As Thomas Bridges traveled throughout the Yahgan region and met more people, he gathered more words to add to his collection, and he was continuously writing words on scraps of paper and copying over his dictionary from one notebook to another so that he could update his list of words.

According to the preface of the 1987 reprint of the dictionary, “The ‘final’ version of 1881 had been preceded by at least 20 others. What happened to these notebooks is unknown. Perhaps Bridges himself destroyed them.”

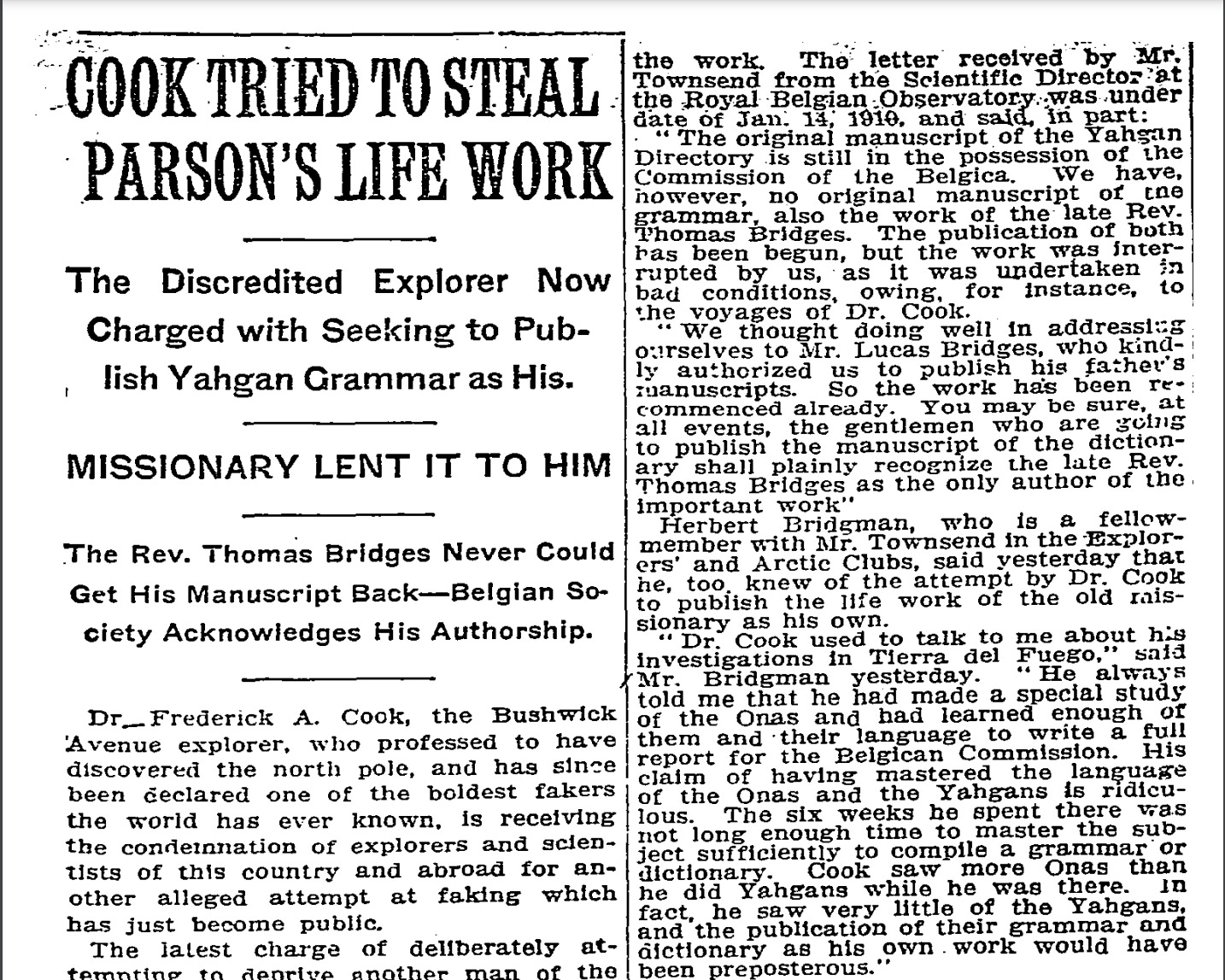

At the beginning of 1898, Thomas Bridges met Dr. Frederick Cook, who was on his way to Antarctica as part of a Belgian expedition to that continent, the first scientific expedition to Antarctica. Dr. Cook told Bridges he knew of an organization in the United States that would be very interested in publishing the Yahgan-English dictionary, and so Bridges promised to entrust his manuscript to Cook when he returned from Antarctica.

Here is where the fascinating saga of the dictionary begins.

Thomas Bridges died of an illness while Cook was in Antarctica—the expedition was trapped in ice over winter and barely managed to survive—but when Cook returned, Mrs. Bridges and Thomas’s children honored his wishes and handed over the dictionary manuscript to Dr. Cook.

Cook wrote the family to describe how the publication had run into difficulties, but then all communication ceased. The family assumed Thomas’s dictionary manuscript was lost.

Several years later, however, advertisements appeared for a soon-to-be published Yahgan-English dictionary—by Dr. Frederick A. Cook. When the Bridges family found out, they protested the false claims of authorship, and the Belgian publishers rearranged the typesetting of the title page to give credit to the Rev. Thomas Bridges.

Publication moved forward under this agreement, but as the process neared completion, Belgium was invaded during World War I. After the war, when communication was restored, the Bridges family discovered that all traces of the nearly-published book had disappeared. Thomas Bridges’ manuscript was lost. Again.

In 1929, a Dr. Ferdinand Hestermann, of the University of Munster, wrote to the Bridges family to say he’d been studying Thomas Bridges’ manuscript for years, and he wanted to know more about its context.

Meanwhile, an Austrian anthropologist and Catholic priest named Martin Gusinde traveled to Chile and Argentina to study the Yahgan. Fr. Gusinde thought the dictionary would be a nice supplement to his anthropological observations, so he connected with Dr. Hestermann and made arrangements with the Bridges family to publish the dictionary. Thomas Bridges’ children (who were, by this time, fairly wealthy from the success of the family sheep farms) covered the costs of publication.

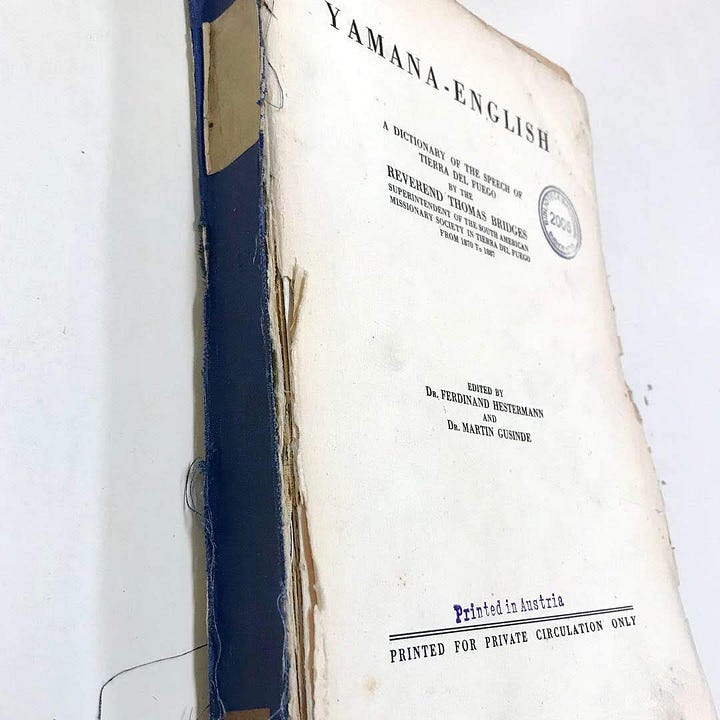

In 1933, Thomas Bridges’ dictionary was published in Austria as The Yamana-English Dictionary. Three hundred copies were printed and sent to scholars and libraries around the world.

The saga doesn’t end there, however.

The Bridges family was eager for their father’s manuscript to become part of the collection of the British Library, but scholarly Dr. Hestermann felt his studies weren’t complete. The family granted him permission to continue to study the notebooks for a little while longer.

Then World War II broke out.

Dr. Hestermann’s last known location was in Hamburg, which the Allies bombed heavily. Around 37,000 people died, and fires destroyed much of the city. The Bridges gave up any hope of hearing from Dr. Hestermann ever again. They assumed their father’s dictionary was lost for a third time.

But a family friend, William Barclay, refused to give up. After the war ended, he called in favors from people in government, and finally the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives commission traced Dr. Hestermann to a farmhouse in the German countryside. The professor pulled from a kitchen cabinet Thomas Bridges’ manuscript of the Yahgan dictionary, which he had been protecting from the Nazis as well as from Allied bombs.4

The dictionary manuscript finally arrived at the British Library (housed, at the time, in the British Museum) on January 9, 1946.

Lucas Bridges, Thomas Bridges’ son, describes the event this way:

“In that historic building which houses the Codex Sinaiticus and so many of the world’s most treasured manuscripts, my father's dictionary found a final resting place. It was proudly displayed in an illuminated case in an otherwise empty room, and a number of those who knew its history came to inspect it and to celebrate the triumphant ending of its adventurous career. Afterwards the party, with Mr. Barclay as host, assembled for lunch in honour of the occasion, the only toast being, 'The Yamana-English Dictionary and its author, the Reverend Thomas Bridges.’”

Thanks to the efforts of Natalie Goodall, an American who married Thomas Bridges’ great-grandson, the dictionary was reprinted in 1987, in honor of the centennial of Harberton (the sheep farm Thomas Bridges established after resigning from the mission).

Thomas Bridges’ dictionary was a remarkable achievement for one man, and it documented the language to an impressive degree.

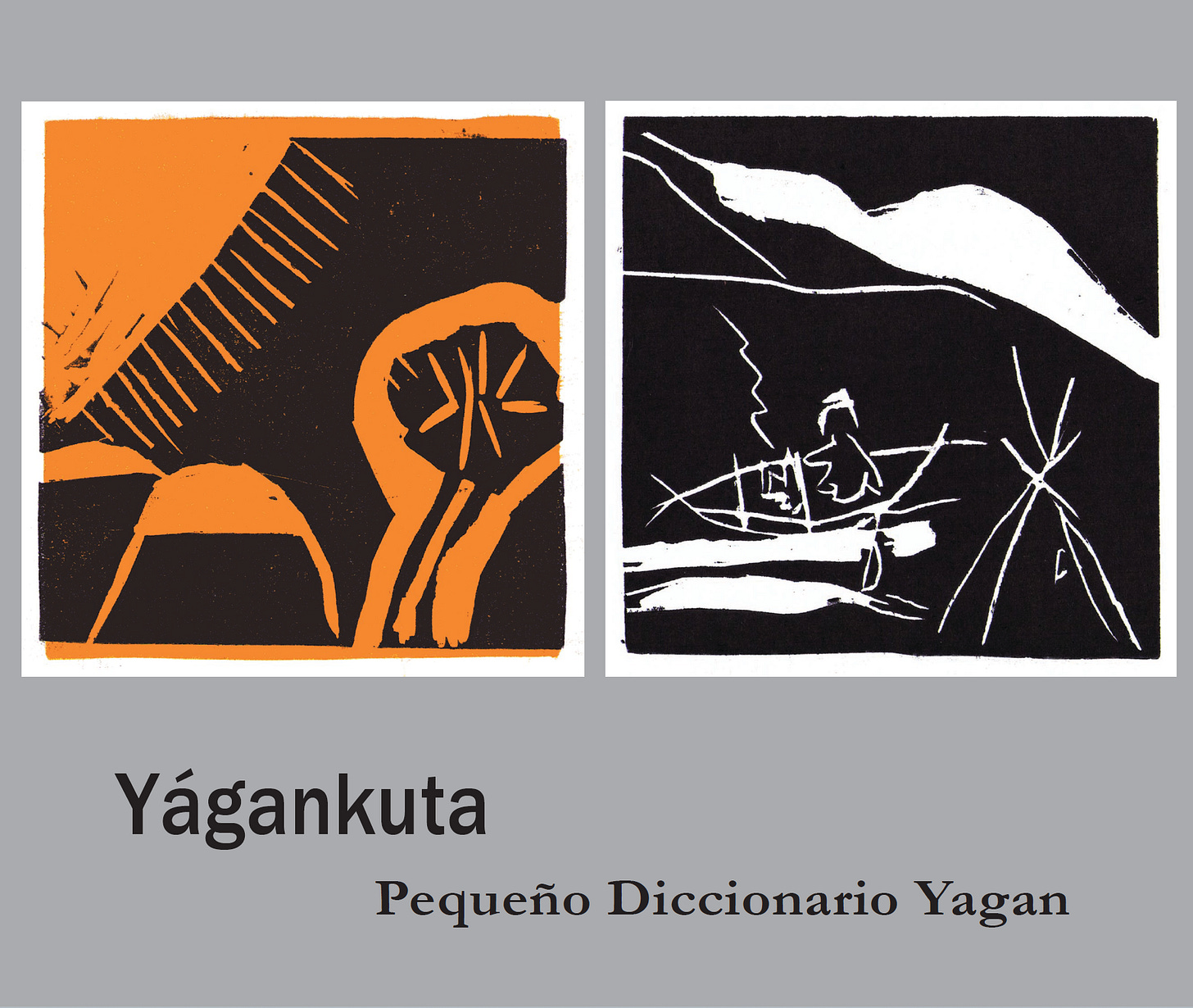

In more recent times, there have been other efforts to keep the language alive, especially among the descendants of the Yahgan who still live in southern Chile and Argentina. Cristina Zárraga, in particular, has organized language workshops and published books to record the language and traditions passed down by her grandmother, Cristina Calderón (who was known as the last fluent speaker). Cristina Zárraga even published an illustrated dictionary of Yahgan words, defined in Spanish.

Through these and other efforts, the remarkably complex language of the Yahgan people continues to be heard in Tierra del Fuego even today.

Sources:

Lucas Bridges, Uttermost Part of the Earth (New York: The Rookery Press, 2007)

Anne Chapman, European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010)

Thomas Bridges, Yamana-English Dictionary of the Speech of Tierra del Fuego, ed. Martin Gusinde and Ferdinand Hestermann (Mödling, Austria: Missionsdrukerei St. Gabriel, 1933)

Natalie Goodall, “Preface to the 1987 version” and “The Odyssey of the Yahgan Dictionary” in Yamana-English Dictionary of the Speech of Tierra del Fuego (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Shanamaiim, 1987)

Cristina Zárraga and Oliver Vogel, Yágankuta: Pequeño diccionario Yagan (Ediciones Pix, 2010)

Charles Darwin did—sort of—change his mind about the Yahgan after hearing about the “civilizing” changes wrought because of the influence of Thomas Bridges’ mission. You can read more about that here.

These figures are according to a “History Facts” email, dated July 12, 2024. Yes, I’m a nerd.

These assumptions of Bridges were probably not actually accurate. He himself noted how often the Yahgan sang songs, and later anthropologists recorded numerous myths and legends passed down through the generations.

According to Lucas Bridges, the BBC aired a news report about the discovery of the dictionary, though I haven’t been able to track down a recording. If anyone knows of a way to search BBC audio archives, please let me know!