The Canoe People of Tierra del Fuego

A brief summary of the past (and present!) of the indigenous Yahgan

Among the Yahgan (also known as the Yamana1), this is the story of how the first people came to be:

For a long time the Yoálox family wandered through the wide world until they finally came to where we Yamana live today. Here they began doing all kinds of work. When the (real) people, who were born right here came into being, the Yoálox taught them how to arrange their lives, how to act toward one another, and how they should interact. The Yoálox also showed the people all kinds of implements and utensils, weapons and tools, and taught them how to use these things successfully. They were, of course, very able men, and consequently invented the various weapons and tools that we use to this day in hunting and fishing, in collecting and killing animals. They also showed us how to reach the animals in the water and on land—the big whales and sea lions, the otters and foxes, the many birds, the shellfish and crustaceans—and how to skin the animals and make the skin serviceable, how to utilize and prepare the meat. All this the Yoálox invented and taught the people. The cleverest of them was Yoálox-tárnuxipa; the younger of her brothers was, in turn, far superior to the elder. From them it can be seen that a younger brother is often smarter and more talented than his elder brother.2

The Yahgan were canoe-based nomads who inhabited the islands between the Beagle Channel and Cape Horn for about 6000 years before the arrival of Europeans. Their population declined drastically during the second half of the 1800s, and after the death of the “last full-blooded” Yahgan in 2022, the people group is usually considered to be extinct. However, over a thousand people still identify as Yahgan today, and legally recognized communities exist in both Chile and Argentina.

Historically, the Yahgan were loosely grouped into four or five “clans” based on dialectical differences and regional divisions, but there was no centralized government of any sort (no “chief” or “judge”) among them. The primary unit of their society was the nuclear family: a man, often several wives, and their children, traveling from place to place together in one canoe. Sometimes closely related family units would travel together, and for occasional special events—like the beaching of a whale or a coming-of-age ceremony—multiple groups would gather for a short time, only to disperse again afterward.

The canoe was the most prized possession of the Yahgan because they used it to get from shore to shore, following food sources. Women were the ones who rowed, freeing the men to hunt and fish with their harpoons. In the bottom of the canoe, people carried a lit fire on a platform of rocks, clay, sand, and grass so that they didn’t have to start a new fire on shore each day.

The early Europeans marveled at the engineering wonder of those canoes, which they considered superior to European boats at navigating treacherous waters, especially during storms. The shape was compared to Venetian gondolas, and they were made of bark and branches held together with animal tendons, whale baleen bristles, or thin pieces of hide.3

The traditional houses of the Yahgan, called ákars, were dome- or cone-shaped structures made of branches, bark, grass, and sea lion hides. The houses were constructed from readily available materials, and they were left standing when the family unit moved to another spot so that they—or another group—could use the house later when they were in that place again. The houses were usually close to the waterline, and the entrance could be moved so that it always faced away from the wind. A fire inside kept the family warm.

One of the primary traditional foods of the Yahgan was shellfish, and they tossed the mollusk shells out the door of their house after eating. Over time, the shells became a ring around the bottom of the structure, up to about a foot tall, that limited the draftiness inside the homes for people sitting or sleeping on the ground. The imprint of those shell mounds are still visible today throughout the shores of the Beagle Channel and the southernmost islands—the clearest marks left behind by those who raised their families, laughed at jokes, and told stories for thousands of years.

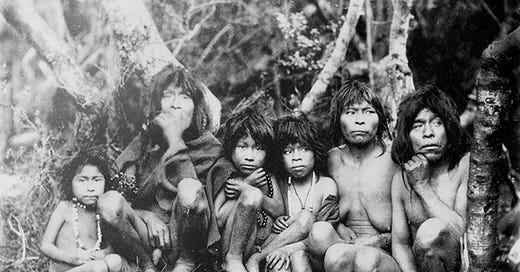

As you can see in the photo above, traditionally Yahgan men and women wore only small front “aprons” hanging from leather or animal tendon belts, as well as necklaces and ankle bracelets. Sometimes people wore small capes that covered their backs, made of seal or sea lion hides. People painted their faces and bodies in dots and dashes using red, white, and black pigments to indicate mourning, marriage, menstruation, or a desire for vengeance. Sometimes face paint was just for fun, and it was also used as part of the coming-of-age initiation ceremony.

There was a lot of misinformation about the Yahgan among European explorers and scientists of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For one thing, Charles Darwin thought they were cannibals and described them as such in The Voyage of the Beagle and his other writings, which were widely read throughout Europe.4 For decades, sailors were as scared of the Yahgan as they were of the dangerous storms and treacherous waterways in the region, and they frequently shot at anyone who approached. The lie of cannibalism proved hard to root out once it was established in the European imagination, but the missionaries worked hard to set the record straight.

Another thing is that Europeans considered the Yahgan “wretched” and unintelligent for wearing so few clothes to protect them from the elements—and repulsive because of the foul smell of the whale or sea lion oil with which the Yahgan covered themselves. It wasn’t until the 20th century that anthropologists realized that the Yahgan were well adapted to their environment and that precisely the lack of clothing and the animal oil helped. Leather—or any other sort of fabric—trapped dampness next to their skin if they got wet from swimming or the rain, while the whale and sea lion oil helped insulate them from the cold.

Tragically, the clothes that European sailors and missionaries gave to the Yahgan as friendly gifts—which the missionaries insisted people needed to wear to be “Christian” and “civilized”—also carried foreign germs and exposed the Yahgan to diseases for which they had no natural immunity.

By the time the missionaries established their influence in the area, the population of the Yahgan had already declined considerably from an estimated 3000 in the 1830s. An unknown epidemic killed a lot of people in the 1860s, and then tuberculosis killed several hundred more in the early 1880s. Thomas Bridges counted 1000 Yahgan in 1884. Then, right after the Argentinian government established an outpost in Ushuaia, a measles outbreak killed several more hundred people. In 1886, there were around 400 Yahgan. The anthropologist Martin Gusinde reported there were 70-80 Yahgan in the early 1920s…but then the deadly Spanish flu swept through right afterwards and killed over a dozen of the principal members of the community.

Neither Chile nor Argentina had a policy of establishing reservations for its indigenous people, the way the US did.5 Many Yahgan moved away to look for jobs and/or intermarried with Spanish-speaking Argentinians or Chileans or people from other ethnic groups. The “last full-blooded” Yahgan woman, Cristina Calderón, died in Feb. 2022, at 93 years of age, and the occasion was announced by news outlets around the world as the death knell of a unique culture and language.6

Several times I’ve been struck by how fascinated people are with “extinct” people groups and those heralded as “the last of” their culture.7 Is it a kind of nostalgia related to what’s perceived as “the end of an era”? I’ve seen sources that announced the Yahgan as “nearly extinct” during the 1880s, the 1920s, and the 2000s. Several times it struck me as lamenting a premature death—particularly when you realize there are a good number of people, alive and well today, who still identify as Yahgan.

When I was in Ushuaia, I attended a tour and cultural orientation given by Víctor Vargas Filgueira at the Museo del Fin del Mundo (Museum of the End of the Earth). Víctor, who is a leader of the Comunidad Indígena Yagán Paiakoala (Paiakoala Indigenous Yahgan Community) in Ushuaia, pointed out that the classification of people as “full-blooded,” distinct from “descendants” of an indigenous group, has colonialist, racist overtones, left over from an era in which people were legally categorized based on how “pure” their European bloodline was.

While the number of Argentinians who identify as Yahgan is unknown,8 the Chilean census of 2017 recorded 1600 people who claimed the label, and there is a significant Yahgan community in Ukika, near Puerto Williams, on the Chilean side of the Beagle Channel.9 Tireless advocates are sharing their language and culture with others through schools, museums, and books.

Let me acknowledge here that it’s a difficult thing to write accurately and fairly about a people group other than your own, especially one that is mostly described through the words foreigners wrote about them, frequently full of misinterpretations and misconceptions. Because of that, I’ve tried in this post to center the life and experience of the Yahgan as recorded in their own words.

In that spirit, let me end with a quote from Cristina Calderón. When asked if she was the last Yahgan, she said, “Of course not. I’m not the only one or the last.”10

The word Yahgan was made up by a foreigner studying the language, but I’ve seen members of the group express their preference for it as a gender neutral term, so it’s what I primarily use. Yahga or Jaga referred to the Murray Narrows, at the heart of the Beagle Channel, where Thomas Bridges judged the “purest” form of the language was spoken, less influenced by other, neighboring indigenous languages. He turned the place name into a name for the language, and—by extension—a way to refer to the whole ethnic group. That became the term used by outsiders around the world for decades. In the 1920s, the Austrian anthropologist Martin Gusinde chose to use the term Yamana (which meant humanity), and that became the name commonly used. But according to the 2010 book by anthropologist Anne Chapman, “The last speakers of the language, Cristina Calderón and her sister Úrsula, explained to me that the term ‘Yamana’ does not apply to them (as a people) because it signifies all humanity: the human being of any nationality, ethnicity or race. They also insisted that ‘Yamana’ signifies the male gender [similar to mankind in English]. For these reasons the Calderón sisters are opposed to the use of ‘Yamana’ to designate their people and prefer to be called Yahgan.”

As a younger sibling, I particularly enjoy this final line. This story was told to Martin Gusinde by an unknown source. I’m quoting from the version translated into English (from Martin Gusinde’s German original) and published in Folk Literature of the Yamana Indians: Martin Gusinde’s Collection of Yamana Narratives, ed. Johannes Wilbert.

A lot of the facts in this post come from Luis Abel Orquera and Ernesto Luis Piana’s anthropological work La vida material y social de los Yámana (The material and social life of the Yamana). It provides a detailed compendium and analysis of earlier sources that describe aspects of the traditional lifestyle of the Yahgan.

The story of Darwin and the Yahgan is worth exploring at length in a post of its own. The short version is that he called them “the most abject and miserable creatures I anywhere beheld,” and said “one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures and inhabitants of the same world.” Darwin thought missionary efforts among them were pointless because they were so “degraded,” but he ended up changing his mind after corresponding the Anglican missionary Thomas Bridges. Darwin was so impressed that he sent a financial gift and letter of support to the mission.

There was a Catholic Salesian mission on Chile’s Dawson Island that operated similar to a reservation from 1889-1911, in the sense that government officials would round up indigenous people (Kawésqar, Selk’nam, and Yahgan) and send them there by force, far from their traditional homes. Many people died from disease, and there are accusations of forced labor. The US policy of establishing indigenous reservations has certainly been destructive to Native American groups (as I understand it, largely because governments purposefully designated the worst land, violated its economic agreements, and forcibly removed children), but it can also be argued that the lack of reservations in Chile and Argentina quickened the disappearance of these people groups by not providing a space with limited outside interference, where their culture and language could be honored and preserved. Instead, the Yahgan and others were relegated to being the lowest class of citizens, often scraping by on menial jobs and surrounded by prejudice. It was common for parents not to pass on their language or their culture because of the disdain and prejudice against “indios” which is still prevalent throughout Latin America today.

See, for example, The Economist, NPR, and the New York Post.

For example, during my childhood trip to Patagonia, on the ferry ride back home we met an indigenous woman selling baskets who told tourists she was the last of her people group. We’ve since tried to remember which people group she was referring to, but we haven’t been able to figure it out.

Prior to 2022, Argentina’s census only asked whether people identified as indigenous, without recording what people group they identified with. The government hasn’t yet published numbers or details of the indigenous population from the 2022 census. Argentina’s census of 2010 counted 955,032 people who self-identified as a “descendent” or a member of an indigenous people group. At the time, there were 35 legally recognized indigenous groups, but Yahgan wasn’t one of them: the Yagán Paiakoala group obtained legal recognition from the Argentinian government in 2021.

It was visiting this area that I was stranded on an island at the end of the world for a week. Upgrade to paid posts to read this story and more!

This quote is my own translation from Cristina Calderón: Memorias de mi abuela yagán (Cristina Calderón: Memories of my Yahgan Grandmother), by Cristina Zárraga. To my knowledge, there are four books currently in print—in either English or Spanish—that present a Yahgan perspective on their own history or culture. Aside from the book mentioned above and another one of Yahgan myths written by Cristina Zárraga, there’s Víctor Vargas Filgueira’s Mi sangre Yagán (My Yahgan Blood) and Patricia Stambuk’s Rosa Yagán: Lakutaia le kipa (published in English as Rosa Yagan: The Last Link). Cristina Zárraga wrote a few other books with her grandmother, but they are currently out of print. There is also this documentary (in Spanish, with English subtitles) that presents an insider’s perspective on the Yahgan’s past and present.

Very interesting, Christine. Cannot wait for your next post!

Also, I am well into your (YA?) novel The Means That Make Us Strangers, and I am enamored of it! The premise is wonderful and your writing admirable. (And, I lived in Greenville for several years after I was first married in 1985; my closest friend lives not too far from there in Campbello, so I still visit occasionally.)