Teaching School in Victorian England

"Ragged" and "dame" schools before universal public education--and how learning about this informed the creation of my fictional character

While researching my novel, I gleaned as many details as I could about the lives of the real-life people my characters are based on. So when I came across a line that said missionary Mary Ann Bridges was a teacher before her marriage, I took note. One source said she was a Sunday school teacher and another remembered her as a schoolteacher, but I couldn’t find solid evidence of either. I wondered, Which would have been more likely for a woman in 1850s England?

It turns out, there may not have been as much of a difference as I assumed between a “Sunday school teacher” and a “schoolteacher,” as women during that time were mostly teaching at charitable institutions for poor children, which sometimes met on Sundays. This is how I found out about “ragged” and “dame” schools in Victorian England.

As a modern-day American, I take for granted government-funded education for kindergarten through high school. I marvel at other countries that offer free preschool for all families or—even better—free university education. And I forget that there are places that don’t offer any sort of education for children—or that government-funded education wasn’t always a norm in countries like the UK.

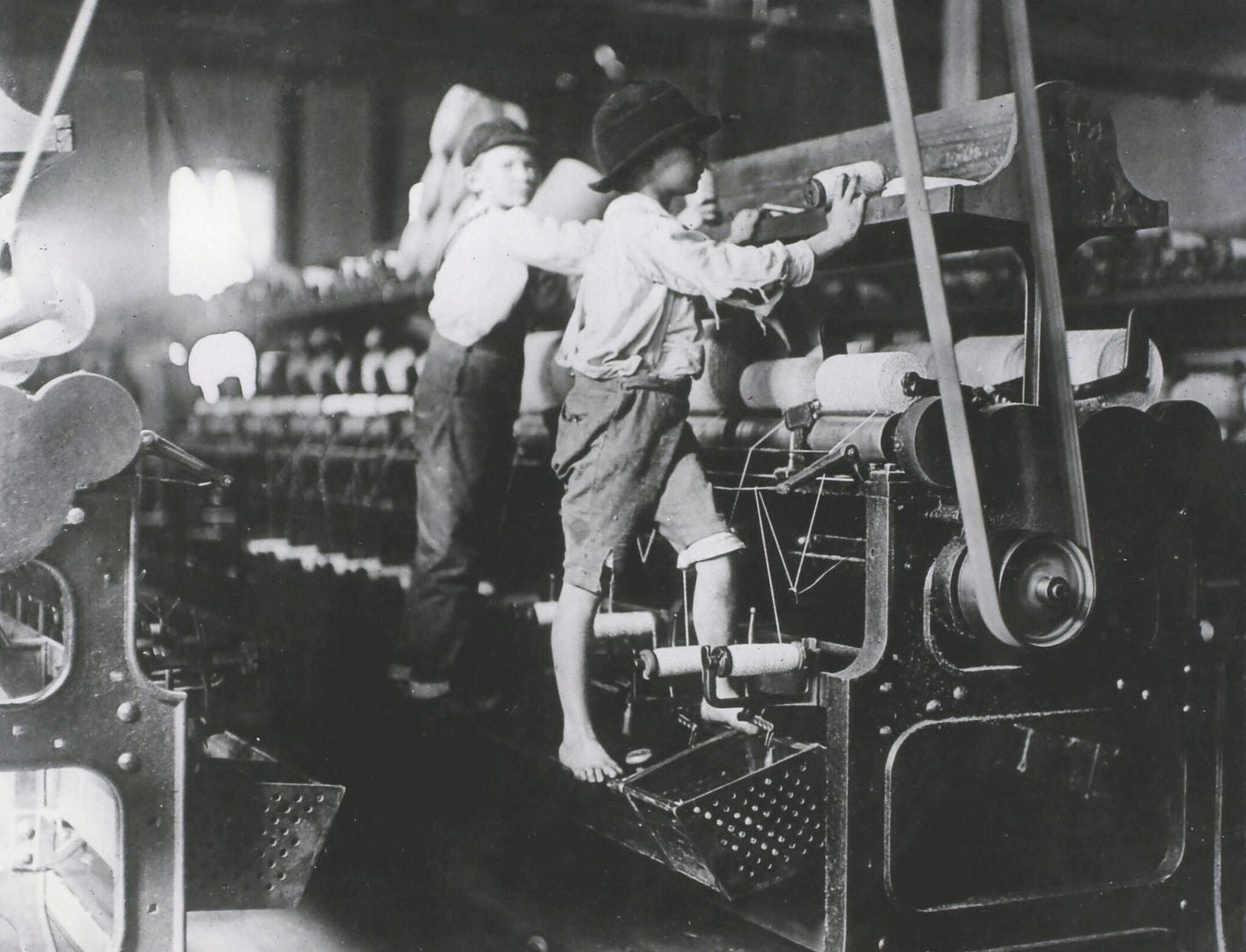

In early Victorian England, “free” education didn’t exist. Families had to fund their children’s schooling, so education was a privilege for the upper and middle classes. If you couldn’t afford to pay someone to teach your children how to read, too bad—but they were probably going to be working a job for which reading would be superfluous anyway.

There was no requirement or expectation for children to go to school. In 1834, one third of children in the city of Manchester had never received any instruction at any school. Instead, children usually worked, 12 to 18 hours a day, to help support their families. Those who weren’t old enough to work frequently wandered the streets, getting into mischief.

In 1820, only around 40% of women and 60% of men in England could read and write.

The wealthy hired governesses to teach their young children at home. Around the age of ten, boys were usually sent to elite and expensive private schools—which are called “public schools” in the UK (don’t ask me why). Girls continued their education at home with the governess, focusing on accomplishments like playing musical instruments and sewing rather than mathematics or foreign languages.

Families from the middle class would most likely send their boys to “grammar schools,” which were sort of like parochial schools, taught by a schoolmaster—always male. These schools were privately run, with little oversight, which meant the quality of the education varied. And the fee meant not everyone could afford to send their sons there.

A less expensive option was to send children to a “dame school,” which was essentially a day care: a woman overseeing a small group of children, usually in her home.1 These teachers didn’t necessarily have much education themselves, so the setup was more about parents paying to give their young children a safe place to go rather than providing them with a solid education.

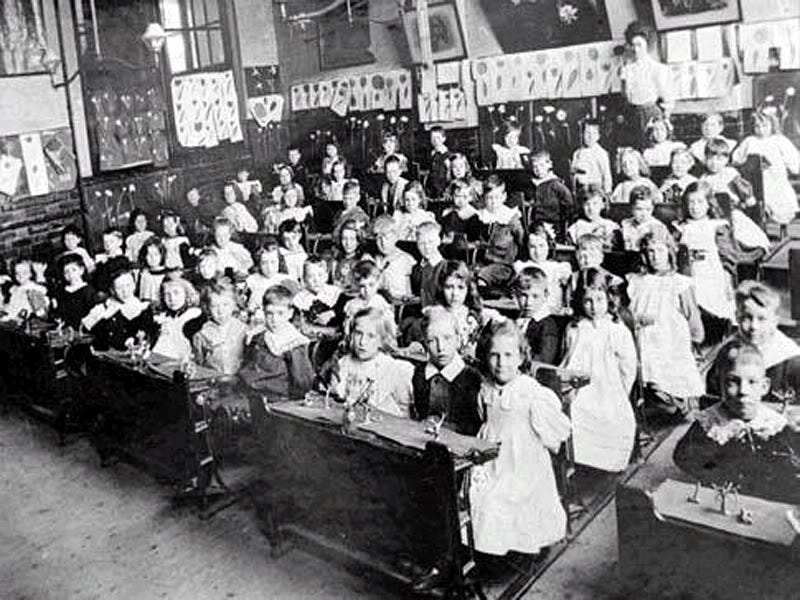

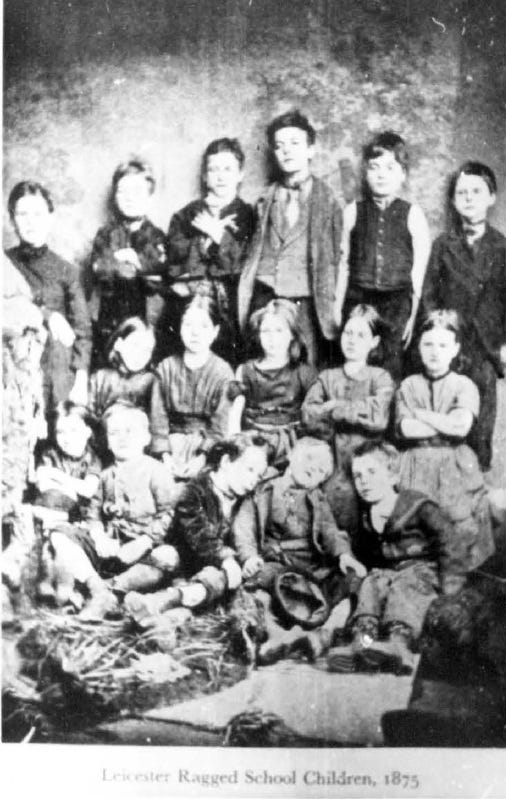

Around 1840, reform-minded individuals began to focus on the problems of the urban poor. “Ragged schools” flourished in cities like Edinburgh, Bristol, and London to provide free education for children who were “thoroughly depraved in mind and ragged in apparel,” “the human vermin neglected by the ministers of state and ministers of religion, heathens in the midst of Christianity.” The schools met in the mornings or evenings or on Sundays, so children could come when they weren’t at work.

The goal was to provide religious education and set up the children for better opportunities in life. In addition to reading, writing, and basic mathematics, children learned work skills such as sewing or gardening. Ragged schools also provided food and clothing, reducing the children’s need to support themselves by working or begging. Schools often helped their pupils find a stable job after they’d finished their education.

Ragged schools were charitable institutions, run on donated funds.2 They relied on volunteers to serve as teachers, which meant many of them were women (since men needed to provide financially for their families). This became the first widespread opportunity for women to teach in a classroom setting—and I imagine it gave women with a social conscience a chance to serve outside of the house, without going too far from home.

In addition to helping children and their families, the ragged school movement argued that it was benefiting the rest of society by reducing juvenile crime. For example, “the Edinburgh Ragged School claimed that, in the first five years of its existence, the percentage of children under fourteen in prison had dropped from 5.6% to 0.9%.”

In 1870, there were over 600 ragged schools in London, with an average attendance of about 60,000 children citywide. It’s estimated that around 300,000 children attended ragged schools in London between 1844 and 1881.

The ragged school movement was so widespread and effective that it prompted a change in the law. In 1870, the British Parliament passed a law to organize a nation-wide educational system—and provide money for poor people to pay school fees. The education of “riff raff” children would no longer depend on charitable institutions.

What I learned from this was that Mary Ann Bridges, the teacher, probably had a classroom full of the urban poor. Suddenly, I saw her as a woman very invested in doing good for others before she became a missionary’s wife. Her personality began to fill out a little, and I had more questions to drive the creation of my fictional character.

The only letter I’ve found from the real-life Mary Ann Bridges contains some unpalatably patronizing language about her indigenous neighbors in Tierra del Fuego, and I confess I had trouble liking the character initially because of that. But picturing her as a teacher gave me a window into a different side to her and helped me start to envision a trajectory for her character—I know how easily idealism and altruism can turn to cynicism. I imagined a scene of her in the classroom to better understand her at that stage of her journey, and this scene eventually became the main picture of her “before” life in the first chapter of my novel.

An explanation of ragged schools and the educational system in Victorian England won’t appear in my book, but learning about this bit of history helped fill in a character’s background and personality so that I, as the writer, could understand her better. And hopefully this will provide a richer experience for readers too.

Sources:

Claire Seymour, “The Benefits of the Ragged Schools Movement,” Ragged University, updated 21 Aug 2023, accessed 27 Dec 2024.

“Victorian Era Ragged Schools for Poor Homeless Children,” VictorianEra.org, accessed 27 Dec 2024.

Laura M. Mair, “The Only Friend I Have in This World”: Ragged School Relationships in England and Scotland, 1844-1870, doctoral thesis for the University of Edinburgh, 2016, accessed 27 Dec 2024.

D. H. Webster, “The Ragged School Movement and the Education of the Poor in the Nineteenth Century,” doctoral thesis for the University of Leicester, 1973, accessed 30 Dec 2024.

I picture Jane Eyre’s small classroom when she’s with the Rivers family. Jane’s dame school would have been an exceptionally good one, because she was actually qualified as a teacher. She would have made significantly more money as a governess at the Rochester house.

Famous wealthy donors included Charles Dickens and the Earl of Shaftesbury. The popular preacher Charles Spurgeon was also a supporter.