Lucas Bridges and His Book

How the middle child of a missionary made his family and the region famous

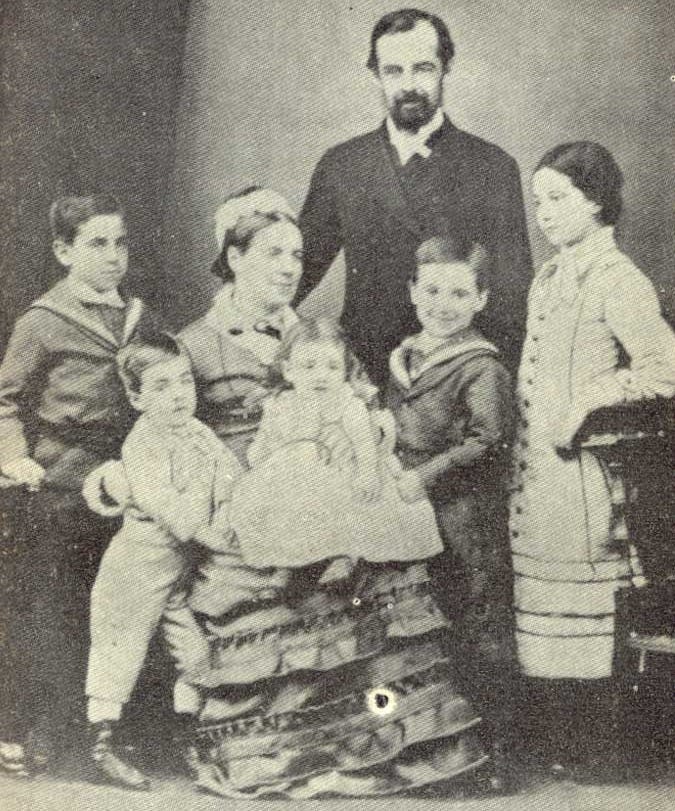

Anyone who passed through Tierra del Fuego during the late 1800s and early 1900s would have heard about the Bridges—first for their role in the Anglican mission in Ushuaia, which created “an outpost of civilization” at the end of the inhabited world, and then for their family sheep farm and store, unique in the eastern part of the Beagle Channel. Thomas Bridges was also well known among anthropologists and linguists for his work with the indigenous Yahgan.

But outside of the small circles of local lore, missionary annals, and those studying the traditional ways of the native Yahgan, the Bridges family would have been forgotten were it not for a memoir written by Lucas Bridges, Thomas Bridges’ son.

Lucas’s retelling of his family’s remarkable history among the native people of Tierra del Fuego has captured the imagination of readers for the last eighty years. It became a must-read classic for anyone interested in the region, and it convinced many to visit the remote archipelago he describes as the Uttermost Part of the Earth.

This book is also the reason I decided to write my novel Fireland.

Stephen Lucas Bridges was born on Dec. 31, 1874, just a few years after his missionary parents became established in Ushuaia. (He later styled his name Esteban Lucas Bridges, using the Spanish version of his name, but he always went by Lucas.) He was his parents’ third child (of six), and the third white child born in Tierra del Fuego.

As he told it, his childhood at the Ushuaia mission was full of capers like climbing trees and outhouses with his brothers, carting around his younger sisters in a wheelbarrow, and going off on boating adventures with his father through the glacier-strewn waters of the Beagle Channel and the surrounding archipelago.

He grew up speaking Yahgan as well as English, and he learned Spanish after the Argentinian government established an outpost (and prison) on the other side of the bay in Ushuaia. One of his language tutors was an ex-convict named Aguirre, who apparently taught Lucas and his brothers a colorful variety of Spanish and manners that didn’t please the British Victorian Mrs. Bridges.

By this time, the Yahgan were already in decline due to wave after wave of epidemics brought by foreign whalers, the Argentinians, and the settled lifestyle encouraged by the missionaries. In 1884, when Lucas was ten, a measles epidemic killed about 60% of the Yahgan within two years. Lucas describes watching his father go off, day after day, to dig graves for the native people, but he spends more time describing how he and his brothers went on fishing expeditions to fend off starvation:

While the Yahgans were still unable to get about, we three brothers had quickly recovered from our mild attack of measles, and were able to [go fishing]. […] On every trip […] we came back with more fish than two of us could carry slung from an oar on our shoulders. Frequently we had to make three or more journeys from the beach to the settlement with our booty. With the exception of those needed by the Mission party, these fish were divided amongst the natives, and we were indeed delighted with ourselves for being the means of bringing these vital supplies to our unfortunate friends—or all that were left of them.

Lucas’s father resigned from the mission in 1886, and the family moved to a plot of land that was given to them by the government. Lucas spent his teen years working on the ranch: tending to the sheep and cattle, building fences, and doing all the other work that was needed.

The family also set up a general store and earned a good amount of money selling fresh meat and other items to the gold miners who flocked to Tierra del Fuego in the 1890s. (They could have made even more money if they’d sold alcohol, but Thomas was a teetotaler and believed the increasing presence of alcohol was bad for the Yahgan.)

The Bridges offered safety to any Yahgan families who wanted to continue to live on the land, and they offered employment to many of them. As the years went on, however, the Yahgan continued to decline, and more and more Selk’nam people arrived from further north, pushed out of their own territory by warfare and genocide at the hands of other sheep farmers.

Lucas eventually learned the language and the customs of the Selk’nam, first by working alongside them as their employer, then by accompanying them on hunts and spending more and more time with them. He learned cultural distinctions between tribal groups and the different quirks of individuals. He was adopted by a particular family and was invited to participate in the initiation rites of their culture. He also advocated for them among outsiders, such as requesting medical help from visiting doctors.

Lucas’s vivid retelling of his experiences among the Selk’nam later made up the bulk of his book. He wasn’t a linguist or an anthropologist, like his father—but he was a storyteller. And few others can claim to have had the experiences he did among the native people of Tierra del Fuego, just as the area was being taken over by outsiders.

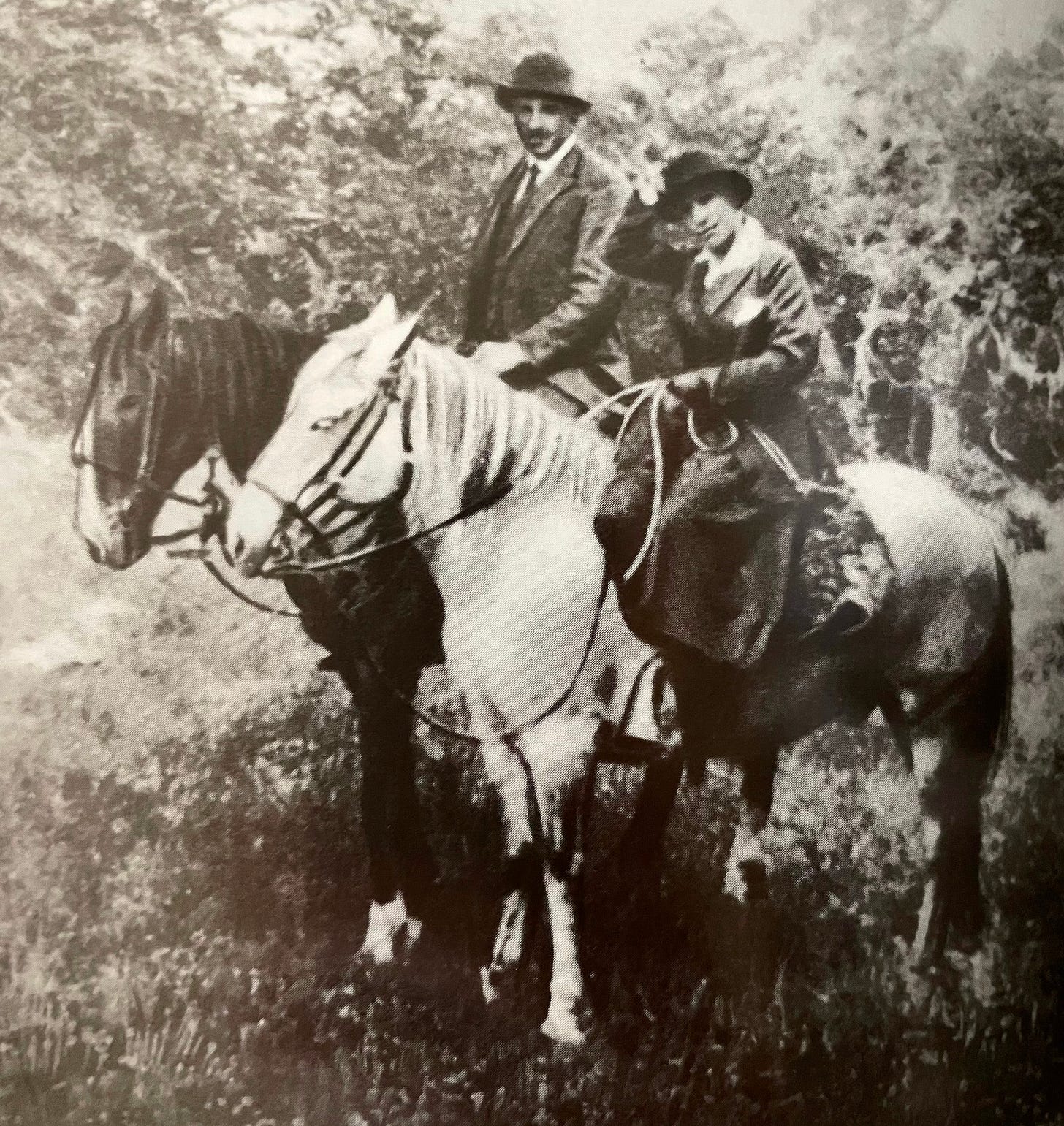

In 1902, Lucas began to develop a second sheep farm in more promising terrain further north on the island. He and his siblings became prosperous there, during a time when wool exports were an important global trade commodity, and they eventually established themselves as one of the major landowning families in Argentinian Tierra del Fuego. They continued to offer safety to the Selk’nam people who wanted to live on the land and employed some—paying them the same wages as white men.

Lucas’s ranching life meant he wasn’t used to civilization. Aside from one year attending a boarding school when he was five (while his family were “back home” in England), he mostly lived free range, dressing like the Selk’nam and ignoring other customs of “civilization.” He reported being bewildered by Buenos Aires when he visited as an adult:

The voyage to Buenos Aires took thirty-one days. When we docked, I was alarmed by the vast number of people in the capital, all striving after something different and getting in each other’s way. For years I had avoided going even to the village of Ushuaia. I had grown as wild and as apprehensive of white strangers and the wary Te-ilh of Najmishk [a Selk’nam man]. […]

I had ridden many an untamed colt and been out boating in the roughest of weathers, yet never had I been so perturbed as when I found myself being whisked along through what seemed a confused whirl of traffic, with a strange—and, for all I knew, undependable—driver in control of the horse.

This didn’t stop him from traveling back to England and enlisting as a soldier when World War I broke out. He was, by then, forty years old, and he had lived in Argentina his entire life except for that one year in early childhood.

A few years later, he married a Scottish woman named Jannette McLeod Jardine, to whom his book is dedicated. They had three children together: a daughter (Stephanie Mary) and two sons (Ian Lucas and David McLeod).

In 1919, just months after being demobilized from the military, Lucas took off for what was then known as Rhodesia, attracted by land that was marked “Unsuitable for white settlement.”

He had just enough time to start that venture before he was called back to South America, to save from ruin his family’s investment in another sheep farm, in a remote valley in southern Chile. Lucas handed over the reins of the African venture to his older brother and spent the next twenty years trying to make the Chilean ranch profitable. His wife and children mostly stayed in England, and he traveled there to spend a few months with them every year.

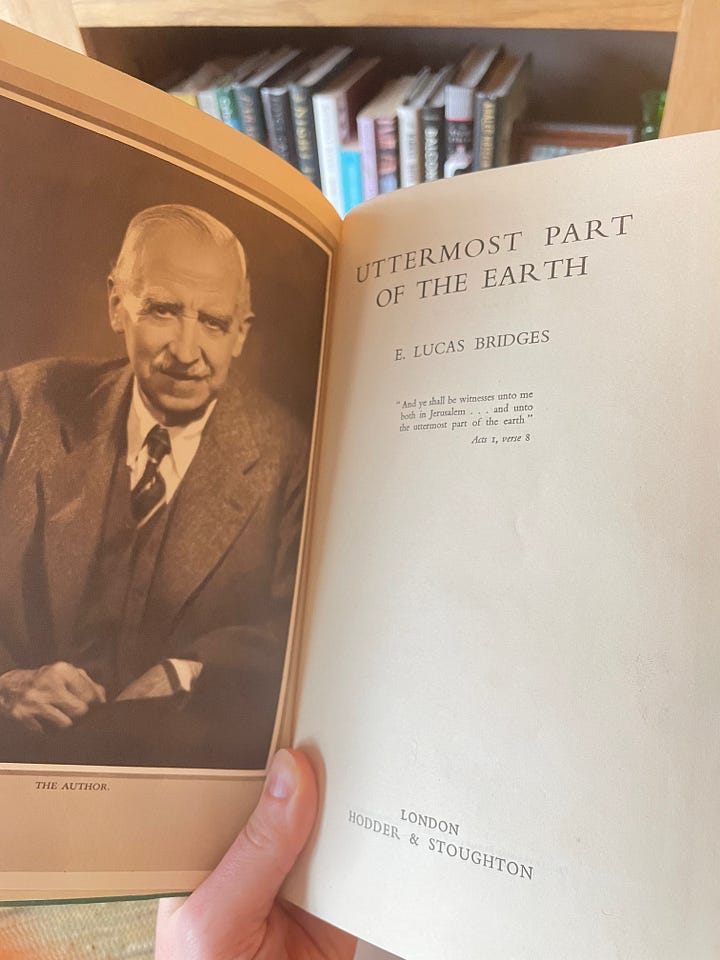

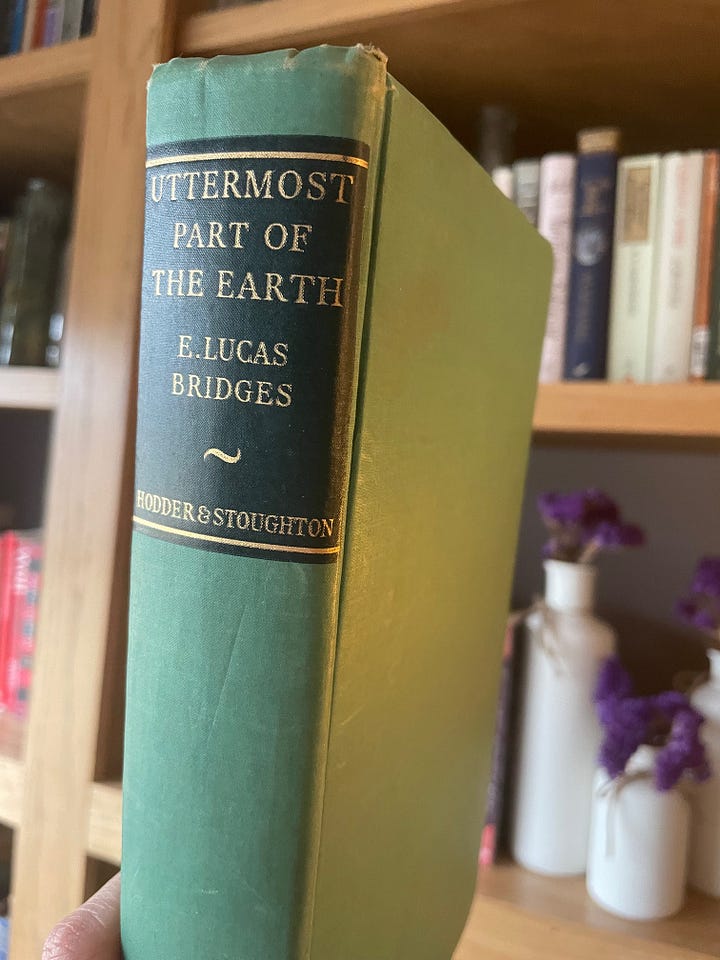

A heart attack in 1944 finally made Lucas give up ranch life. He moved to an apartment in a fancy part of Buenos Aires with his wife, and there he began to work on his book, fulfilling a promise he’d made to the celebrated travel writer Aime Tschiffely. Using anecdotes from his father’s diaries and his own memories, Lucas compiled the book that became Uttermost Part of the Earth: A History of Tierra del Fuego and the Fuegians.

The book was published in London in 1948: a year before the author’s death.

To our tastes today, the book is sentimental and uneven—sometimes a bit of a slog. Lucas writes about his family history in glowing terms, making his parents into saints. He shares the story of the place and its native people from a perspective that is patronizing at times. He poses as an objective observer and offers little personal introspection. He takes pages and pages to describe a guanaco hunt but dedicates only half a page to the untimely passing of his father.

It’s easy to get lost in all of the anecdotes about different native people…and yet there’s unquestionable value in the fact that Lucas writes about the Selk’nam as individuals, with a degree of insider knowledge that no other writer can claim.

The English book was out of print for many years, but it was widely acknowledged as a classic on Tierra del Fuego. It was named in 2004 as “one of the 104 best first-person accounts of exploration in English of the twentieth century” by the Explorers Club. Descendants of the Bridges published a new English edition in 2007, and it is still sold in bookstores in Tierra del Fuego and elsewhere.

My mom doesn’t remember how she first came across the book, but she probably picked it up on our family trip to Patagonia when I was nine. In any case, my mom was struck by the incredible drama of the Bridges’ story (despite the tedious description of hunting guanaco). She told me quite a few times that there was a great novel there…and eventually, after quite a few years, I realized she was right.

Lucas Bridges’ story became my starting point, as I too, became captivated by his family’s story—including what lay between the lines of his book, the stories he didn’t tell, with the emotional complexity I could imagine into being. I’ve since read lots of other books in my research on Tierra del Fuego and its people, but none of the other books on my bookshelf has nearly as many sticky notes poking out of its pages.

I’m not at all hoping my novel could take the place of Lucas’s book—instead, I hope my imagined story will someday complement his memories, as only a novel can.