Human Zoos

How indigenous people in Tierra del Fuego were kidnapped and put on display in Europe and the US

To understand the context of the first missionaries in Tierra del Fuego, we have to talk about human zoos and how, during the same time period the mission was established, indigenous people were exhibited in the major cities of Europe and the United States for the entertainment of gawking citizens enthralled by the exoticism of “savage” “cannibals.”

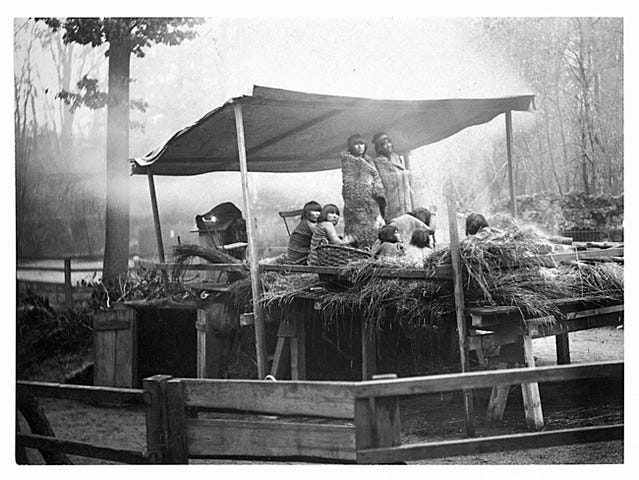

A product of colonialism, humans zoos were most popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s. By one estimate, as many as 25,000 indigenous people from Africa, Asia, North and South America, Australia, Greenland, and Finland were put on display. The exhibits definitely catered more to the viewers’ expectations of primitive cultures than than to accuracy of representation, and many of the “performers” were required to dress differently or change their hairstyles to match what the fair organizers wanted.

The largest human zoo ever assembled was for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, often called the St. Louis World’s Fair. “An estimated ten thousand people […] lived for its duration on the grounds and were exhibited in ersatz reconstructions of their ‘native habitats’ for curious visitors to Forest Park. Among them were Ainu people from Japan, ‘Patagonians’ from the Andes, and members of fifty-one of the First Nations of North America.”1

Many of those who were put on display in human zoos were paid a wage of some sort, but the 11 Kawésqar people who were kidnapped in Tierra del Fuego in 1881 were most definitely not paid, and they were not given a choice about going to Europe, about being put on display, or about having their bodies minutely measured by anthropologists. Only four survived and made it back to Southern Chile.

These 11 Kawésqar (Alacaluf) people were kidnapped by a German sealer living in Punta Arenas, known as Herr Waalen, who probably lured them onto his boat individually or in small groups through offers of food. They were taken first to France and exhibited in Paris at the Jardin Zoologique d'Acclimatation, which is today a children’s park.

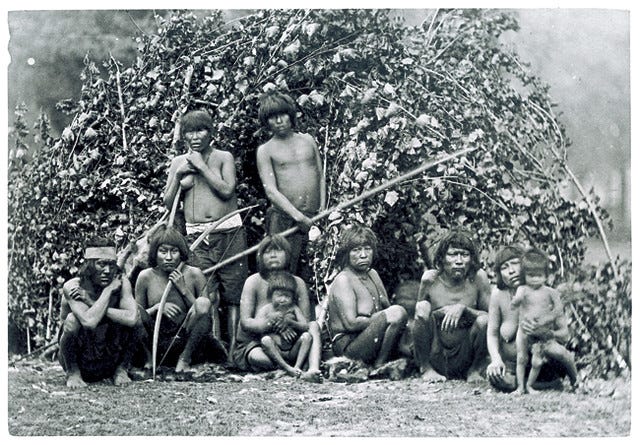

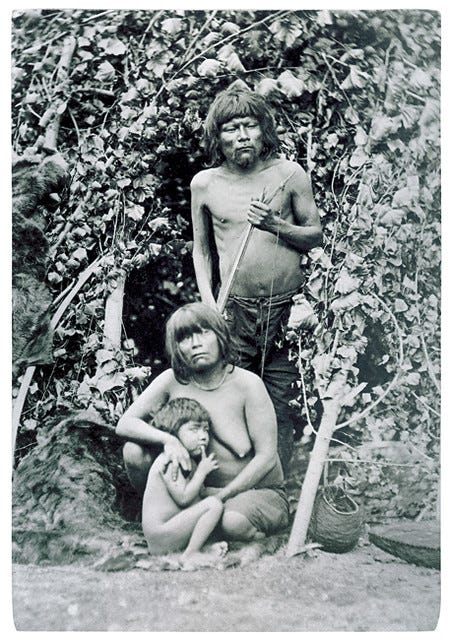

Their enclosure was furnished with a canoe, “a hut made of branches, prominently displayed bones and an open fire around which the captives huddled, thus creating a scene depicting ‘the savages—the primitive cannibals—of Tierra del Fuego.’”2

It didn’t matter that the Kawésqar weren’t cannibals—no indigenous people in Tierra del Fuego were cannibals or had ever been cannibals. Labelling them as such attracted more attention to the exhibit.

Thousands of park visitors came to stare at the men, women, and children in the enclosures. Park visitors jeered and threw coins at them, which the Kawésqar ignored (coins being unusual in their part of the world) until they realized the metal disks could buy them useful things, like combs and baskets.

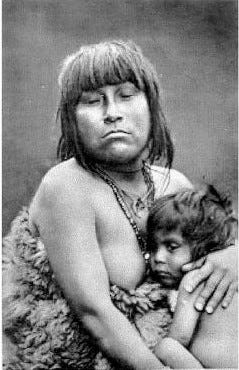

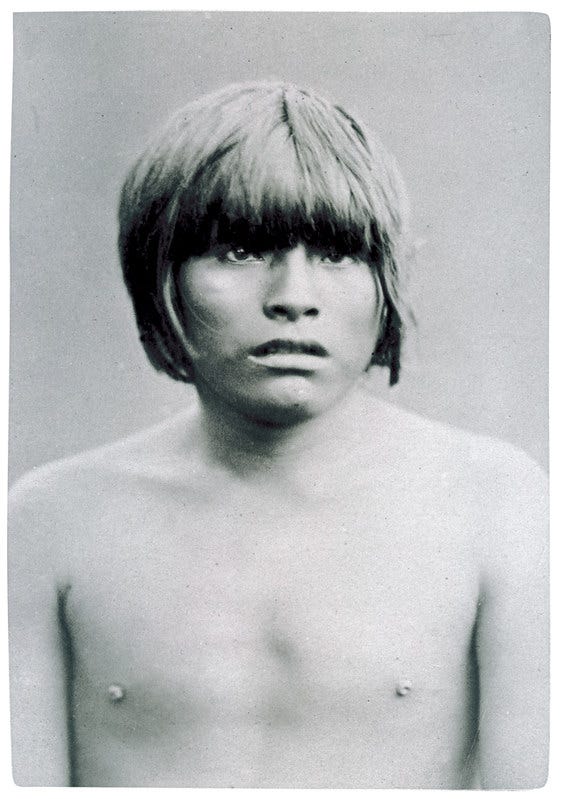

Members of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris visited them to take photographs and measurements of their bodies for anthropological research, which were later referenced in a debate trying to pinpoint the exact, physical reason they were inferior to white Europeans.3

The group of Kawésqar were likely kidnapped in different places, because none of the adults were related to each other, except for one man and woman who were a couple, known as El Capitán and Piskouna, who had with them an infant son. There were two other mothers, known as Catherine and Petite Mere (Little Mother), with their young children. There was another single adult woman, known as Lise; a single adult man, known as Antonio the Fierce; and two teenage boys, known as Henri and Pedro. The only names we have for them now are the names the French gave them.

Petite Mere’s baby died less than a month after they arrived in Paris. The ten others were taken to Berlin, then Leipzig, then Munich. In Munich, Lise died. The others were taken to Stuttgart, Nuremberg, and finally Zurich. By that time, all of them were unhealthy or very sick. At least one of the women had syphilis, which she did not have when she left her homeland.

Petite Mere, Catherine, El Capitán, and Henri died in Zurich. Antonio either died in Zurich or on the voyage to or from Zurich. The four Kawésqar who remained alive were too ill to be exhibited, so they were returned to Tierra del Fuego and dropped at the Anglican mission in Ushuaia on July 23, 1882. Thomas Bridges surprised them by speaking to them in their own language, using the few words that he knew.4

In March of 1883, the teenage Pedro, Piskouna and her son were returned to their Kawésqar homeland, in the northwestern part of Tierra del Fuego. The little girl who was Catherine’s daughter stayed at the mission orphanage. The last that we know of her is that she survived the measles epidemic that struck Ushuaia in 1884 because she had been inoculated in Paris.

In 1885, Pedro returned to Ushuaia, leading a group of families who were hoping to find refuge from the increasing violence against them. The Kawésqar group was welcomed by Thomas Bridges and the Yahgan, but the mission was suffering the after-effects of the measles epidemic and didn’t survive intact much longer.

The skeletons of the four kidnapped Kawésqar who died in Zurich were kept at the Plattenarten Museum until 2010, when the remains were repatriated to Chile thanks to the advocacy of Kawésqar Chileans and historian Christian Baez, who extensively researched indigenous South Americans in human zoos.

During the 1880s, at least twenty-five indigenous Selk’nam, Kawéskar, and Tehuelche people from southern Chile and Argentina were part of human zoos in Europe.5 These people were captured and transported with the knowledge of the local and national governments.

Human zoos continued into the 20th century. At the 1958 Worlds Fair in Brussels, there were 598 people on display in a Congolese village exhibit. One of the children at the village died. In the 1990s, near Nantes, France, a theme park known as Safari Africaine included an exhibit of a village from the Ivory Coast, complete with performers who were “hired” to entertain visitors to the park. The performers’ passports were confiscated by the park organizers, they were paid ¼ of the French minimum wage, they were forced to sleep in the village installations, they were rarely allowed to leave the park, and they were attended to by the park’s vets instead of doctors when they got sick. Human rights groups complained until the performers were released.

Of course this is all tied up with the blatant racism that backs colonialism, which requires a differentiation of “us” from “them” in order to diminish “them.” It’s been argued that human zoos also contributed to the rise of Nazi ideology.

Against this background, the missionaries who treated the indigenous Fuegians with dignity and respect stand out as all the more extraordinary. Though they for sure got a lot of things wrong—I often struggle with the patronizing attitude of the missionaries’ writings and their insistence on teaching a European lifestyle as part of the Christian message—it’s important to judge the missionaries within their context. They believed that indigenous people had souls worth saving and intellect worth engaging, rather than treating them as “savages” to be gawked at, in a day and time when Europeans and Americans thought it perfectly appropriate to display humans in zoo exhibits alongside animals.

Sources:

Christian Báez Allende, Cautivos: Fueguinos y patagones en zoológicos humanos (Santiago, Chile: Pehuén Editores, 2018)

Christian Báez and Peter Mason, Zoológicos humanos: Fotografías de fueguinos y mapuche en el Jardin d'Acclimatation en París, siglo XIX (Santiago, Chile: Pehuén Editores, 2006)

Anne Chapman, European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010), 492-508

Carlos Gamerro, La jaula de los Onas (Buenos Aires: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2021)

Walter Johnson, “The Largest Human Zoo in World History,” published 14 April 2020 in Lapham’s Quarterly, accessed 1 April 2024

Leonce Manouvrier, “The Fuegians of the Jardin d'Acclimatation,” trans. and ed. Robert K. Stevenson, first presented 17 November 1881 at the Anthropology Society of Paris

Justine Reix, “The Racist Zoo Where Visitors Paid to See Black People in the 90s,” published 15 March 2022 by Vice, accessed 1 April 2024

Sara Shahriari, “Human Zoo: For Centuries, Indigenous Peoples Were Displayed as Novelties,” published by 30 Aug 2011 by ICT News, a division of IndiJ Public Media, updated 13 Sept 2018, accessed 1 April 2024

Photos downloaded from the flickr album “Fueguinos. Fotografías siglos XIX y XX

Imágenes e imaginarios del fin del mundo” by Pehuén Editores.

This quote is from “The Largest Human Zoo in World History,” published in Lapham’s Quarterly. One of the people who was brought to St. Louis for the World’s Fair was Ota Benga, a Congolese man. After the fair closed, he went to New York and was exhibited in the Bronx Zoo in a cage with an orangutan. African American journalists and clergymen successfully advocated for his release, and he eventually went to work in a tobacco factory in Lynchburg, Virginia, until he died by suicide in 1916.

This is from Anne Chapman’s European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin, p. 493. My retelling is indebted to Chapman’s account of the Kawésqar’s travails for many details and for being one of the first places I learned about the Fuegian natives taken to human zoos.

That debate ended up being futile. No criteria the anthropologists selected was upheld by facts. They tried to argue cranial proportions, arm length, and different mental faculties, but in each case the measurements of the Kawésqar people were deemed to be equal or superior to Europeans’. This frustrated the anthropologists to no end, since they all agreed in the “common sense” presupposition of the Fuegians’ inferiority.

The Kawésqar are linguistically and ethnically distinct from the Yahgan, among whom Thomas Bridges lived and worked—meaning their languages aren’t mutually understandable and they don’t share common ancestry. Their traditional cultures did share a number of similarities, however, as both groups had adapted to their surroundings by becoming canoe-based nomads. Thomas Bridges made many attempts over the years to reach the other people groups of Tierra del Fuego—the Kawésqar (Alacaluf), the Selk’nam (Ona), and the Manek’enk (Haush). He made the most progress connecting with the Kawésqar, but his knowledge of their language and culture was much more limited than his knowledge of the Yahgans’.

I say “at least” because those are the known cases, with documentation, but it’s possible there were more. There were also indigenous Chileans who were similarly displayed in cities throughout Chile, according to historian Christian Baez.

A 2021 novel by Argentinian author Carlos Gamerro, La jaula de los onas (The Cage of the Onas), tells a fictionalized version of the story of the some of the captives taken to Europe. To my knowledge, the book is only available in Spanish, but I’m planning on writing a review of it—along with other novels set in Tierra del Fuego or about Fuegians—for a future post. Stay tuned for that.

Wow! Always so excited to read your posts! As a History major in undergrad, 100 years ago :), I can tell you I have never heard or read anything about this. So interesting, and unnerving. Thank you for your informative reports. I look forward to reading them every week, and am learning much about Tierra del Fuego and its people. Can't wait for Fireland!