The Patagonian Welsh

How a community of immigrants carries on the language and culture of Victorian Wales in Southern Argentina

There are several reasons I find fascinating the Hulu show Welcome to Wrexham, a documentary about two Hollywood actors’ purchase of a Welsh football (soccer) team. I appreciate the portrayal of the actors’ developing friendship and the dynamics of the Welsh town, where the team is an important part of residents’ daily lives. Particularly fun was when an episode in the third season intersected with another of my interests by highlighting Wrexham fans in Argentina—specifically a part of Argentinian Patagonia that was settled by Welsh immigrants in the 1800s and still preserves aspects of Welsh culture, like the language.

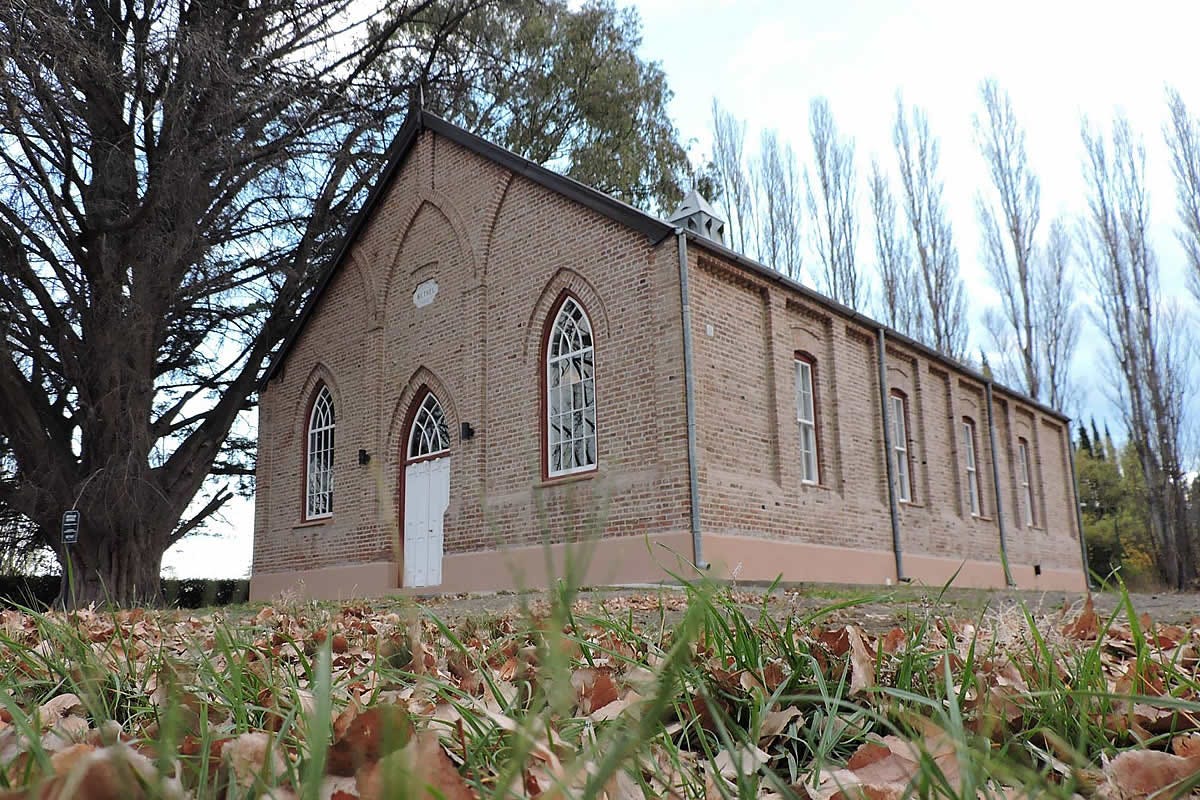

No description of Southern Argentina is complete without mentioning the Welsh settlement of the Chubut Valley, known as Y Wladfa (“The Colony”). Today, tourists visit brick chapels and tea houses to experience Welsh traditions passed down through the generations, while descendants of the original settlers attend bilingual Spanish-Welsh schools and celebrate their heritage in an annual music and literary festival called the Eisteddfod.

The most interesting thing, I think, is the way the Patagonian Welsh community adapted inherited Welsh traditions for a new environment, creating a vibrant and unique culture all its own.

The first Welsh settlers were a group of 153 that arrived in Argentina in 1865. The Industrial Revolution had decimated Welsh agricultural communities and increased tensions between the Welsh and the English, who were the bosses and political rulers. There was widespread prejudice against the Welsh, described as “ignorant, idle and immoral,” in at least one official English report. Children were forbidden to speak Welsh in schools. In response, several hundreds of thousands of people left Wales during the 1800s.

More than 250,000 moved to the US (particularly California and Wisconsin), and a good number more settled in Canada, Australia, or New Zealand. Many of these immigrants quickly assimilated. This loss of Welsh language and culture was a problem for some people, who felt it was important to preserve a particular Welsh identity that was being threatened in Wales itself.

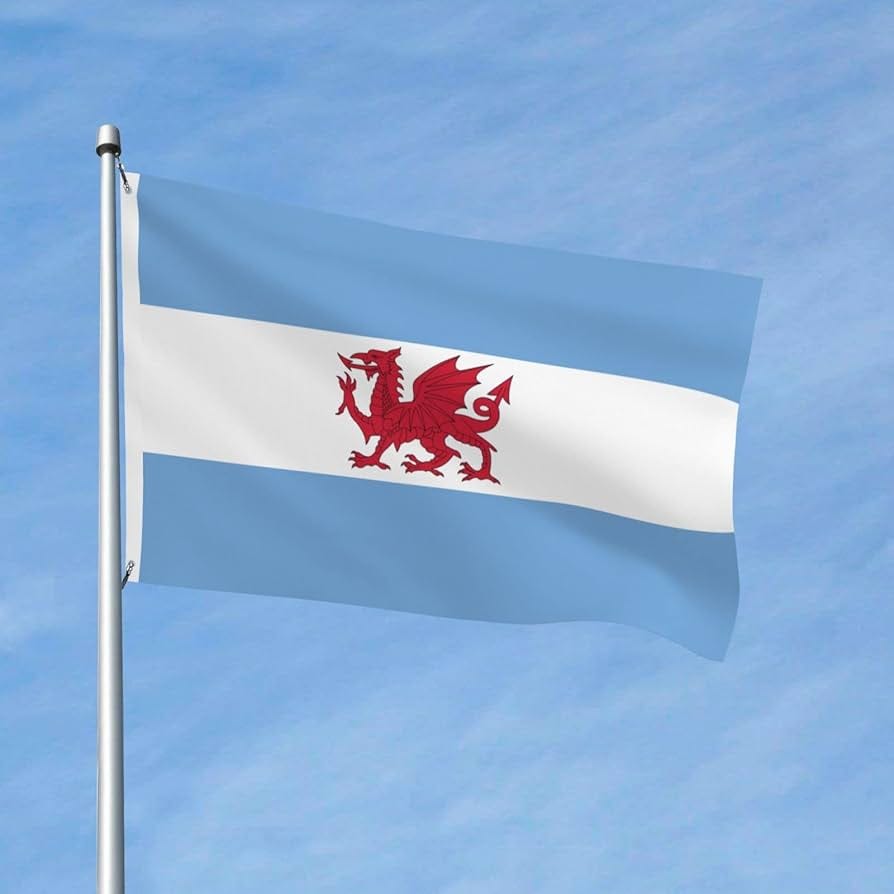

The Rev. Michael D. Jones became a chief proponent of emigration to a place where Welsh people could preserve their language and culture and nonconformist Christianity, free from English influence. He picked Patagonia as a promising site because of its isolation.

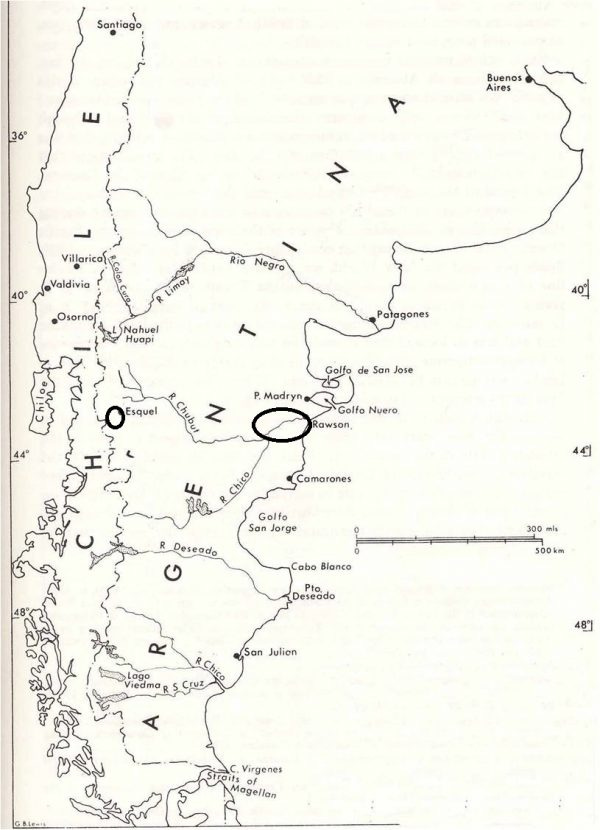

At the time, Patagonia was contested between Chile and Argentina, so Buenos Aires granted the Welsh settlers 100 square miles along the Chubut river to support Argentina’s claim on the land.

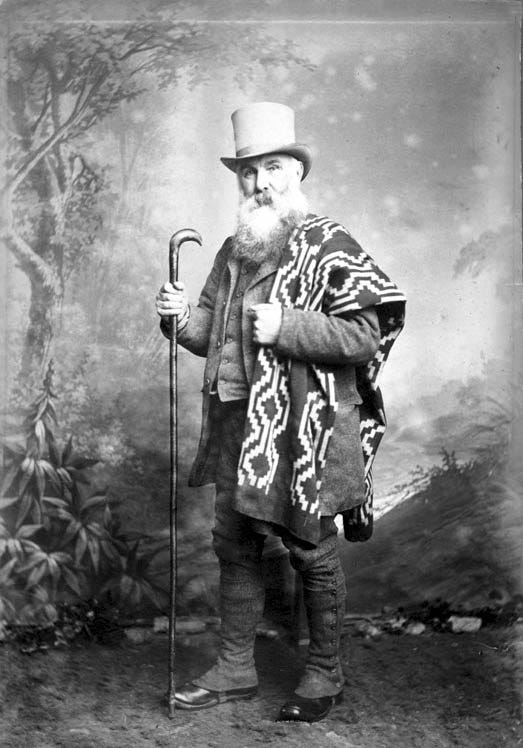

When the first settlers arrived in Patagonia, they found a different sort of place than had been advertised. One settler described it this way:

“If God made the earth, the devil made Patagonia and he made it as like to his own special home as two pies.”

Despite hardships, the settlers learned to hunt and fish local game like guanaco and ostrich. They also developed a system of canals to irrigate a swath of the valley, which created some of the most fertile wheatland in Argentina. Within a decade, the settlers were basically self-sufficient.

Several more waves of immigration followed in the 1880s and early 1900s. In total, around 2300 Welsh people migrated directly to Patagonia before World War I brought a stop to immigration from the UK.

Previously, the area had been inhabited by Tehuelche people, who were the target of genocide in the Argentinian “Conquest of the Desert.” Part of the reason the Buenos Aires government accepted and encouraged the Welsh immigrants was that it wanted European settlers to take the place of the “uncivilized” nomads who resisted Argentinian influence in what had been their homeland.

The Argentinian government even provided the Welsh colonists with weapons, ammunition, and training to use against the Tehuelche. The Welsh, however, developed a mostly friendly relationship with nearby indigenous people. They traded with the Tehuelche and learned from them how to survive in the arid land. They used the weapons for hunting instead of fighting.

Cooperation between the two groups became part of the legend of the Welsh in Patagonia, and yet there is the complexity that the Welsh settlers were colonizers who themselves were escaping colonization by the English.

The Welsh community in Patagonia prospered over the decades. They formed a farming cooperative. They built a railroad to ease transportation of harvests to the coast. They built chapels in every community, so that no one had to travel very far to worship. They established an annual festival, the Eisteddfod, with a poetry competition.

Because literacy was highly prized and encouraged among these settlers, there are quite a few written records that contribute to the legend and the renown of the group. The courage of the early settlers was praised in their own first-hand accounts as well as by their descendants, and the stories have been passed down with a greater degree of continuity than they might otherwise have been.

According to one source,

Dr Iwan Rees, an expert in Welsh-American studies who lectures at Cardiff University, believes that the Chubut settlement is the world’s strongest Welsh diaspora in terms of the intergenerational transmission of Welsh and the strength of the Welsh language and culture at a community level. “It’s only in this region, for example, that we find the fourth, and even fifth generation of speakers who speak Welsh as a first language,” he says.

Today, there are about 70,000 Patagonians of Welsh descent. Of those, maybe 5,000 speak Welsh. There are three bilingual Welsh-Spanish elementary schools and a Welsh-Spanish language school for all ages.

The Patagonian colony has particular significance for Welsh nationalists as the emblem of a place where Welsh culture has survived against all odds. In 1965, a group of people traveled from Wales to Patagonia to celebrate the centennial of the settlement, and since then, there’s been a good bit of interaction and exchange between Welsh Patagonians and Wales. Welsh teachers are sent from Wales each year, and some Welsh Patagonians travel to Wales for intensive language immersion opportunities. The Patagonians even asked the Welsh government to send television programs in Welsh to encourage language development.

Bruce Chatwin’s bestselling travel memoir In Patagonia, published in 1977, brought attention to the Welsh community in Argentina through dramatizing anecdotes of drinking tea with Welsh speakers and retelling stories of the early Welsh immigrants.

And, more recently, the community was featured in Welcome to Wrexham, in an episode that follows five Welsh Patagonian fans who travel to Wales for the first time to attend a match, courtesy of the football team and its sponsors.

There’s a scene in the Welcome to Wrexham episode in which the Argentinian fans have a chance to take the stage at an event in Wrexham, and a young woman who grew up speaking Welsh in Argentina addresses the gathered crowd in Welsh. The scene is memorable to me not only because of the emotion of the Argentinian fans, who felt they had returned to an ancestral homeland, but also because of the blank faces of the crowd that heard them speak.

Today, only about a third of the residents of Wales understand spoken Welsh. About 28% of the population is able to speak it, though many fewer speak it daily. The majority of the Welsh crowd assembled that day wouldn’t have been able to understand the Welsh spoken by the visitor from Argentina. And, in any case, Patagonian Welsh is a distinct dialect, with loan words from English and Spanish that don’t appear in other dialects of Welsh.

This is what’s most fascinating to me about the Patagonian Welsh—how they’ve kept alive the idea of a culture, inherited from ancestors who lived in Wales in the 1800s. And yet, really, their culture is something different and unique: ancestral Welsh traditions forged into a new shape through the hardships they faced in Patagonia and mixed with traditions of other immigrant groups that settled nearby.

For example, the highlight of a Welsh Patagonian tea house is “torta negra galés” (Welsh black cake)—which is actually a Patagonian invention, born from the Welsh community there, not traditionally Welsh. It uses ingredients and methods that were available to the early settlers.

The annual Eisteddfod festival holds poetry competitions in the Welsh tradition, but there are contests in both Welsh and Spanish. The majority of the participants speak Spanish primarily.

I see this as the beauty of the immigrant experience, proof that culture is fluid and dynamic, a living thing that changes as it adapts to new environments and interacts with surrounding cultures. This, in turn, is part of what immigrants have to offer to both their home culture and the surrounding majority culture: a vibrant new take on old traditions, remixed and reimagined into something unique.

Sources:

Chris Moss, “Y Wladfa: The Welsh in Patagonia,” in Patagonia: A Cultural History, part of the series Landscapes of the Imagination (Oxford: Signal Books, 2008).

Tara Loader Wilkinson, “The Land of My Fathers,” BBC.com Storyworks, accessed 9 June 2025.

“Welsh Chapels in Patagonia,” The Story of Nonconformity in Wales by Addoldai Cymru, accessed 9 June 2025.

Bruce Chatwin, In Patagonia (New York: Penguin Books, 2003)