How the Author of "The Little Prince" Influenced Daily Life in Southern Argentina

It wasn't because of the children's book

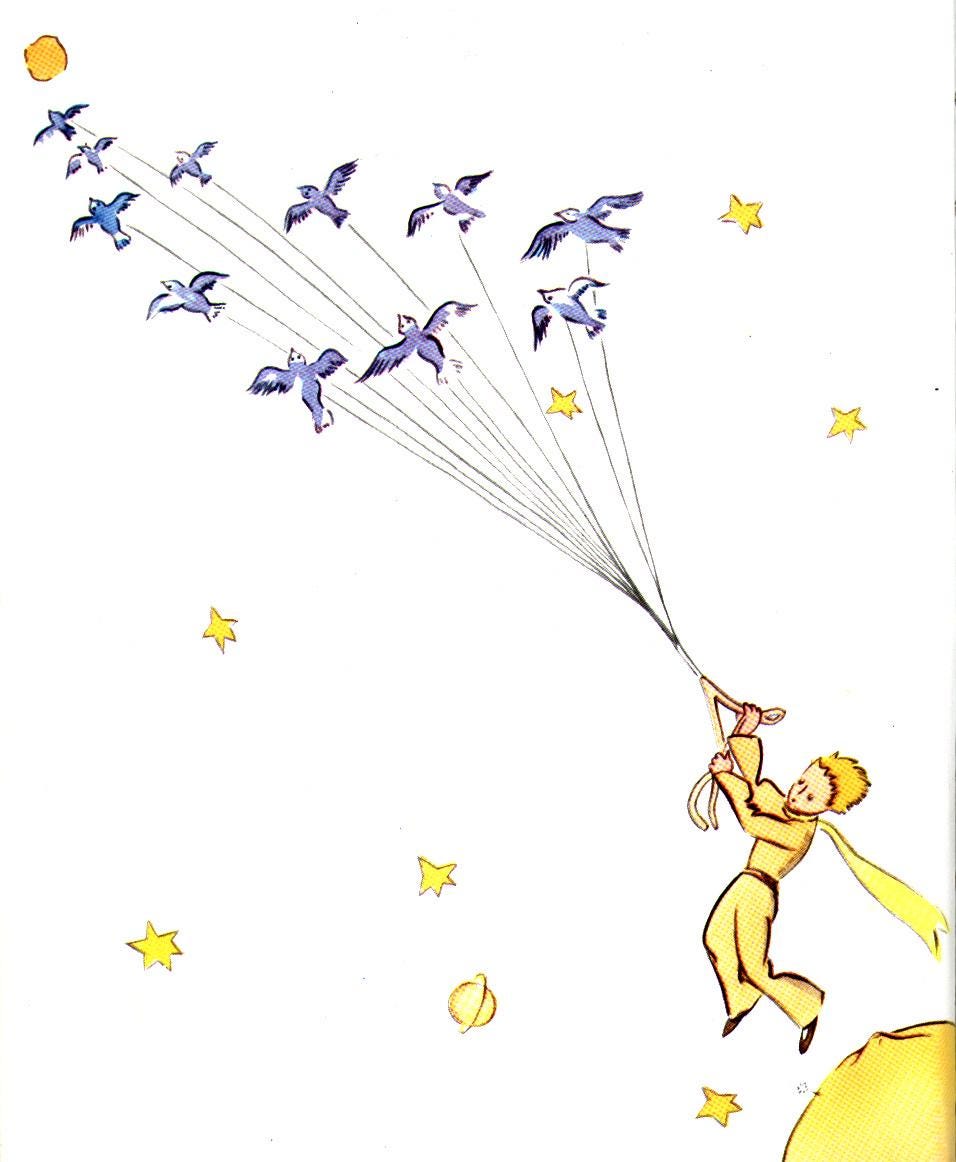

I’m excited about today’s post for two reasons: first, because of my affection for the strange and tender French children’s novella The Little Prince, which was introduced to me by my Colombian best friend from high school.

And, second, because of the fascinating story of how Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author, was instrumental in connecting southern Argentina to the rest of the world through air travel.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry lived in Argentina only a little over a year, but he was instrumental in pushing the boundaries of air travel further south as director of the Aeroposta Argentina.

Until 1928, the only way to get to Tierra del Fuego was by boat. By steamship (already much faster than sailboat), it took a couple of weeks to travel between Ushuaia and Buenos Aires, which lies about 1500 miles away.

But in the late 1920s and early 1930s, dramatic advances in aviation suddenly made it possible to get from southern Argentina to Buenos Aires in two to three days. Air mail made regular communication much easier, and passengers could travel much more quickly if they needed medical care or had urgent business in the capital.

Argentina left its mark on Saint-Exupéry as well. His biographical novel Night Flight, which won him literary acclaim, is based on his experiences in Argentina as a pilot, and an unplanned landing in northern Argentina may have inspired some of the story and imagery of his children’s book. He also met his wife, Salvadorean artist Consuelo de Sandoval, in Buenos Aires.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry was born to a family of aristocrats in Lyon, France, but the death of his father, four years later, impoverished the family. In his twenties, he took private flying lessons and joined the French Air Force. In an era when airplanes had few instruments, he went to work for the Compagnie Générale Aéropostale, a French commercial air mail company, overseeing the route in Northern Africa.

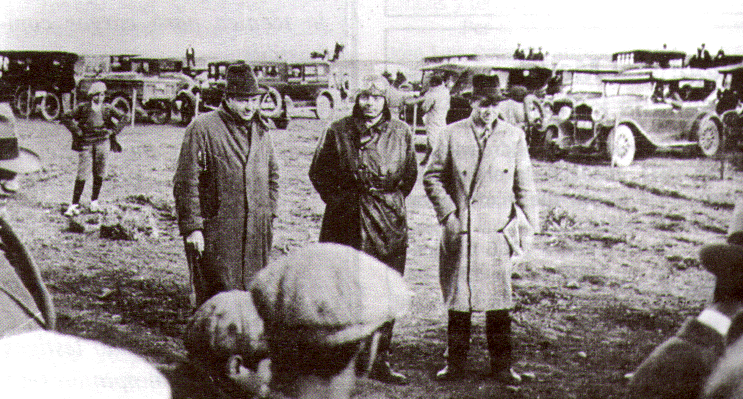

In 1929, he was named director of the company’s Argentinian branch, Aeroposta Argentina. He arrived two weeks before the projected expansion of the mail route to the south, and he took charge of the final preparations.

On the morning of Nov. 1, 1929, to great fanfare, Saint-Exupéry piloted the first plane to deliver mail to the city of Comodoro Rivadavia, in Chubut Province, Argentina. The route was challenging because of high wind velocities on the ground and in the air, as well as extreme temperatures in winter, but in the first year of its operation, the company transported 644 passengers and 7500 pounds of mail on this leg between Comodoro Rivadavia and Bahía Blanca.

To put Saint-Exupéry’s flights into context, the Wright brothers’ first airplane flight was in 1903, and in 1927, Charles Lindbergh was the first pilot to cross the Atlantic without stopping. So these were still the early days of flight travel, when airplane pilots were daring explorers and heroes.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry encouraged his pilots to fly by night, a risky endeavor with few instruments or safeguards. He wrote a novel, published in France in 1931, based on his own experiences flying at night in the harsh Patagonian winds. The book was immediately translated into English (as Night Flight) and, in 1933, was made into a movie starring Clark Gable.

On March 31, 1930, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry launched regular flights to Río Gallegos, reaching the southern part of Patagonia. In 1934, the route was expanded to the city of Río Grande, in Tierra del Fuego, but landing in Ushuaia was considered too difficult at the time. It wasn’t until 1948 that commercial flights were established between Ushuaia and Buenos Aires.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry also expanded the mail route to the north of Buenos Aires. On one of his surveillance trips, in 1929, mechanical problems forced him to land in a field in the northern Argentinian province of Concordia. On landing, a fox hole broke the wheel of his plane.

Two girls came out to investigate, and the pilot was surprised when he overheard them making fun of him in French, his native language. Saint-Exupéry felt as if he had stepped into a fairy tale when he saw their mysterious, castle-like home in such a remote location. He became friends with this French family, and he described his experiences among them in a chapter of his book Wind, Sand, and Stars, published in 1939.

Some of the same animals and imagery from that experience show up in the story of The Little Prince, as does the personality of the youngest daughter of the family, Edda.

Saint-Exupéry left Argentina to return to France in January 1931. He gained literary acclaim for his novels, but he also continued his exploits in aviation. In 1935, in an air race from Paris to Saigon, his plane went down in the Sahara, and he was saved from dehydration by a passing Bedouin. (Those who are familiar with The Little Prince will recognize the plight of a pilot stranded in a desert from the beginning of the book.)

During World War II, Saint-Exupéry flew reconnaissance missions for the French air force, but he escaped France when the country was invaded by Germany. He spent the next few years in North America, mostly New York and Quebec. It was in New York, in 1942, that he wrote The Little Prince, which was published in the US in both English and French.

By this point, significantly debilitated from the cumulative effects of previous airplane crashes and eight years beyond the cutoff age for military pilots, he petitioned for special permission to fly in the US Air Force and the Free French Air Forces.

His plane disappeared on a reconnaissance mission in the Mediterranean, on July 21, 1944. A bracelet with his name was recovered in 1998, and remnants from his plane were recovered in 2003. The remnants are now housed in the French Air and Space Museum in Paris, where a special exhibit honors his exploits in aviation.

In 1995, another Hollywood movie, Wings of Courage, was made based on his experience with the air mail routes in South America, showing this daring pilot’s influence in Argentina continues to inspire.

Sources:

“Antoine de Saint Exupéry y su huella en Argentina,” Instituto Saint Exupéry, accessed Sept. 2, 2024.

Heather Jasper, “An Unexpected Destination Inspired a Beloved Children’s Book,” Fodor’s Travel, published Sept. 25, 2023, accessed Sept. 2, 2024.

Alina Dieste, “Argentine Castle Evokes Enigmatic Visit by ‘Little Prince’ Author,” Buenos Aires Times, published Sept. 13, 2023, accessed Sept. 2, 2024.