"Falklands" and "Malvinas"

The complicated history between Argentina and the British territory of the Falkland Islands

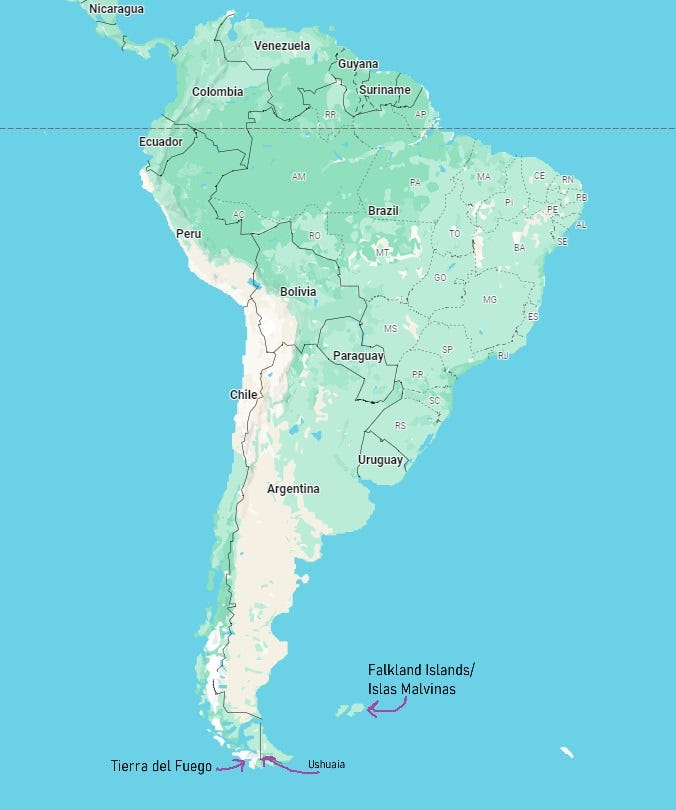

You can’t talk long about the history of Tierra del Fuego without also mentioning the Falkland Islands (known to Argentinians as the Islas Malvinas).

In the 1800s, settlers in Tierra del Fuego depended on resupply ships from the Falklands, and visitors to the South Atlantic region would most likely stop in the Falklands before facing the notoriously dangerous waters around Cape Horn. And you can’t visit Ushuaia today without encountering some mention of the 1982 war between Argentina and the UK over the Falklands/Malvinas—or the continuing Argentinian claim to the islands.

For the story that I tell in my novel, about the Anglican missionaries to Tierra del Fuego and the indigenous people they worked with, the Falkland Islands played an important role.

But why are the two regions so interconnected? And why do the Islas Malvinas/Falkland Islands loom so large in the Argentinian self-image? Let’s do a quick overview of the islands’ history to try to answer those questions.

The Falklands had no native population before European immigration began.1 The first settlement was French, established on East Falkland in 1764 and ceded, soon after, to Spain. Britain founded its own settlement on one of the small islands in 1765, which Spain captured in 1770. War nearly broke out, but then Spain restored the settlement to Britain in 1771 to avoid open conflict.

You could say there’s been tension over the islands ever since, with Argentina inheriting Spain’s claim when the former colony declared independence in 1816.

For much of the early 1800s, however, there were no permanent inhabitants in the Falklands, and the islands were only visited by fishermen, whalers, and sealers of different nationalities. Then Britain asserted its claim over the whole archipelago in 1833 by sending British forces to occupy the islands. Argentina protested, but it was in the middle of a civil war, so it couldn’t do much about the situation.

Britain encouraged its citizens to immigrate to the islands, particularly Scottish shepherds, since the climate was somewhat similar to Scotland’s. The city of Port Stanley (now known simply as Stanley) became the seat of government in 1845, and it quickly grew in importance as a trade center because it offered ship repair capabilities and fresh supplies (such as meat from the sheep that thrived on the islands).

When British missionary Allen Gardiner and his companions died in Tierra del Fuego in 1851, they starved to death waiting on provisions that were supposed to come from the Falklands.2 The missions society Gardiner founded carried on his vision to establish a missions base in the Falklands for the purpose of reaching the Yahgan (from a safe distance, since they were considered to be dangerous cannibals, thanks to Charles Darwin’s mistake).

The missionaries’ plan was to convince friendly Yahgans to go to the Falklands to learn the basics of Christianity along with reading, farming, and the British style of dress. Thomas Bridges lived on the Keppel Island mission station for fifteen years, until he and his family moved to Ushuaia in 1871. It was at the Keppel station, as a teenager, that Bridges first learned the Yahgan language and started compiling his dictionary. Thomas Bridges’ first child (his daughter Mary) was born in Stanley, as was his granddaughter Clarita, before there was a civilian doctor in Ushuaia.

From 1856 until 1898, the South American Missionary Society had a training school and farm on Keppel Island, which functioned at first as the headquarters of the Tierra del Fuego outreach and then as an ancillary to the settlement in Ushuaia. The two locations supported each other for practical reasons: Differences in climate meant more certain crops could grow on Keppel Island that didn’t thrive in Tierra del Fuego, and Tierra del Fuego’s timber provided essential fuel and construction materials for the treeless Falklands.

The Falkland Islands, as a British territory, provided an important military base for the UK during both world wars. A battle was fought there in 1914, which led to the defeat of a German squadron.

Argentina, however, didn’t forget its claim on the islands. In the mid 20th century, Argentinian president Juan Perón (husband of Evita, known in the US because of the musical) raised the issue again. In the 1960s, the issue of Falkland sovereignty was debated in the UN as an issue of colonization, and the UK and Argentina discussed the possibility of a transfer of the islands to Argentina, pending the agreement of the islanders. Falklanders, however, lobbied strongly in the UK Parliament against the transfer, and the discussions stopped.

In 1979-1980, under Margaret Thatcher, government belt-tightening in the UK meant Britain was interested in offloading the islands, so it approached Argentina to resume talks of a transfer. But again serious discussion petered out before the two sides could reach an agreement.

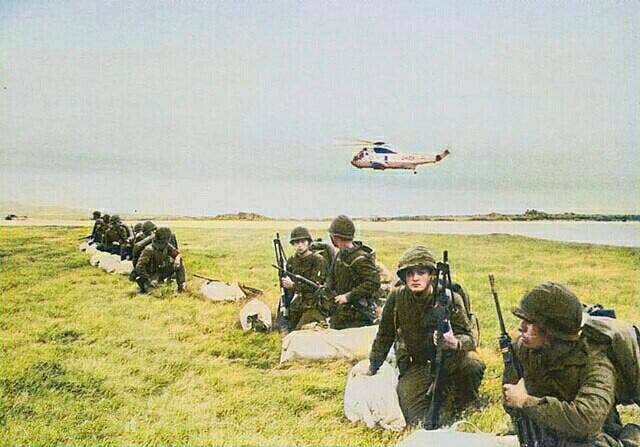

Then, in April of 1982, Argentina’s government initiated a military campaign to claim the islands by force.

Argentina at this time had a military-run government, product of a 1976 coup that had suspended Congress, political parties, and provincial governments. Secret police was “disappearing” (kidnapping, torturing, and killing) between 9,000 and 30,000 of its own citizens who were suspected of supporting communists or harboring anti-government sentiment. What made the president even more unpopular was economic stagnation. So, to prop up his administration, the president took decisive action in the Falklands.

Soldiers arrived by ship, plane, and helicopter. They took control of the capital city, raised the Argentinian flag, and held about a hundred residents hostage.

Argentina’s president gambled that the UK wouldn’t send troops to the faraway outpost that it didn’t want anyway, but that gamble proved to be wrong. Thatcher dispatched British ships and planes in defense of the islanders. Fighting lasted for two and a half months, resulting in 649 deaths on the Argentinian side and 225 on the British side. Three Falkland Islanders were also killed.

In the conflict, Chile sided with the UK rather than its neighbor—the only Latin American country to do so—because resentments lingered over the 1978 almost-war between Chile and Argentina.

Argentina was unable to hold its position in the island, and its troops surrendered on June 14, 1982. The defeat eventually led to the Argentinian president’s removal from office and the restoration of democracy in the country.3

The date is commemorated as a national holiday in the Falkland Islands, known as Liberation Day.

Currently, the islands are a British self-governing overseas territory. A 2013 referendum asked the Falklanders how they wanted to self-identify, and 99.8% voted to remain a part of the UK. The UK handles defense and foreign affairs, and the Falklands use the British pound, but they are self-governing in everything else.

The official UN name for the islands is “Falkland Islands (Malvinas)” in English and “Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands)” in Spanish.

About 80% of the 3,700 inhabitants live in Stanley, the capital. Fishing and sheep farming are the largest industries, along with tourism. Potentially exploitable oil fields have been discovered in the area, however—which could add volatile fuel to the longstanding conflict of sovereignty.

Argentina still officially claims the islands. The defeat is very much still a sore point, very present in the minds of residents in Tierra del Fuego. Many of the soldiers who fought were local boys, and every city in Tierra del Fuego that I visited has a prominent memorial to those who fought and died. Ushuaia also has a museum about the 1982 conflict, and murals throughout the city make reference to it.

The very name of the Argentinian region translates into English as “Province of Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica and Islands of the South Atlantic,” with the Malvinas being the principal islands Argentinians think of. Maps of the province—and of the country—always include the Falklands.

“Las Malvinas son nuestras,” (the Malvinas are ours) is a rallying cry for patriotism in Argentina. I learned to always refer to the “Islas Malvinas” when talking to an Argentinian, even if we were speaking English.4

Conversely, the official website of the Falkland Islands tells potential tourists:

You may have heard the term ‘Malvinas’ used to describe the ‘Falkland Islands’ – some people incorrectly believe that this is the Spanish or Portuguese translation, however it is a word that Argentina uses to assert their sovereignty claim over our home and therefore using it is considered highly offensive here; in Spanish please use Islas Falkland and in Portuguese Ilhas Falkland.

In an interview with the BBC in May of 2024, Argentinian president Javier Milei “vowed to get the islands back through diplomatic channels.” His tone was apparently notably different from previous presidents’ in his acknowledgement that the islands currently belong to the United Kingdom and in his refusal to reassert sovereignty through any means necessary, including open conflict with the UK.

One chapter of my novel is set in the Falkland Islands, at the Anglican mission base, prior to the Bridges’ transfer to Ushuaia. Though the vast majority of the novel takes place in Tierra del Fuego, I wanted to include this setting since it was an important component of the missionaries’ world.

The translation into Spanish, however, was tricky. My Argentinian friend who translated the manuscript (and recently sent it back to me!) specifically consulted me about the issue. I told her I didn’t want to offend Argentinian readers on this sensitive issue, and I’d go with whatever she thought was best. She opted to mostly use “Islas Falkland” as a reflection of the characters’ British mindset. In one instance, however, “Malvinas” was clearly a better choice, when a character is speaking to an Argentinian official in the 1970s and her loyalty is under question.

As a foreigner in Argentina, the issue of the Malvinas/Falklands was hard for me to understand, but now I see it as yet another interesting aspect of this fascinating part of the world. While I don’t draw attention to the issue in my novel, I hope what I’ve learned about the complicated history adds texture to the reading experience for the benefit of those who enjoy well-researched historical fiction.

Sources:

Ione Wells, “Falklands dispute may last decades - Argentina president,” BBC.com, published 6 May 2024, accessed 5 Nov 2024.

“Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas),” The World Factbook, CIA.gov, updated 28 Oct 2024, accessed 4 Nov 2024.

“Falkland Islands,” Britannica.com, updated 30 Oct 2024, accessed 5 Nov 2024.

FalklandIslands.com, Falkland Islands Tourist Board, accessed 5 Nov 2024.

“Early Settlements—Keppel Island Mission,” Falklands-SouthAtlantic.com, accessed 4 Nov 2024.

Some archeologists think seafaring Yahgan from Tierra del Fuego explored the islands or maybe settled there at some point, which is interesting to consider in light of the later Anglican connection between the two regions. But the point remains that the islands were uninhabited by the time the Europeans showed up.

One interesting part of this story is that Gardiner’s wife, who was back in England, wrote to an Admiral Sulivan, stationed in the Falklands, asking him to send a ship to check on Gardiner and the others. The letter was delayed, and by the time it arrived in the Falklands, Sulivan had left. The letter didn’t reach him until 1865, by which time Gardiner was well known as a martyr for the missionary cause.

In 1986, he was sent to prison for mismanaging the war in the Falklands. (Notably, not for ordering the killing of Argentinian citizens—those charges came later.)

The term “Malvinas” actually comes from the original French name for the islands, which were named after the port of Saint-Malo, France.